Helping Students Grapple with Primary Sources

A MiddleWeb Blog

But only recently have I remembered how incomprehensible such sources can initially appear to our students.

This summer I’ve been taking an online course on the history of emancipation during the Civil War. For the first week’s assignment, I read the primary sources before the secondary accounts and found myself confused by the order and content of events, looking up question after question online.

I was also brought up short by the 19th-century language. It was comprehensible, but barely, and only if I read several degrees more slowly than usual.

Abraham Lincoln’s language, especially, asked for contemplation. The documents by Lincoln that I knew from years of teaching seemed straightforward: his First and Second Inaugurals, the Emancipation Proclamation.

First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation to the Cabinet

But, I realized as I read unfamiliar sources, these speeches were straightforward only because I already knew them.

My own struggle has made me think about how we teach primary sources to our own students. When should we give context beforehand, and when should we encourage students to muddle through difficult language themselves?

3 ways to teach with primary sources

Here are three ways to approach primary sources deeply, each with its own benefits:

- Open-Ended Inquiry: Ask students to read primary sources without context, forcing them to grapple with themes and questions on their own.

I did this inadvertently when I plowed through the sources for my emancipation class without reading the secondary text first.

Pros: Students ponder what each document says and create their own argument and context. They may remember the conclusions better because they had to work to find them, and they feel a sense of achievement at cracking the code of these complicated texts.

Cons: Much like an open-ended science lab, this approach requires a great deal of time and one-on-one attention from the teacher. Students may also come away with misconceptions about the meaning of events.

- Enhance the Textbook: Pick a document that makes part of the textbook come alive in ways students would not have anticipated.

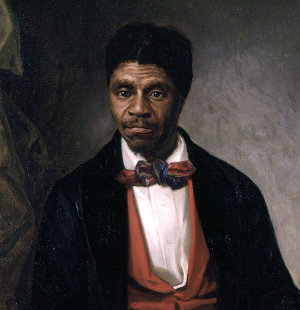

In the emancipation class, I read Roger Taney’s opinion in the 1857 Dred Scott case for the first time.

Dred Scott, 1882 painting based on 1857 photograph

Many times I had discussed the particulars of the case with my students, culminating with Taney’s insistence that African-Americans could never be citizens under the Constitution.

Yet to read the Chief Justice’s assertion, among others, that the authors of the Declaration of Independence “knew that it would not in any part of the civilized world be supposed to embrace the negro race” led me to write in the margin: This is insanity! The words whisked me straight to 1857, war looming, the Supreme Court discredited among half the states.

This “in the moment” incorporation of primary sources is probably the most common method I’ve used, with everything from Ulysses Grant’s memoirs of the surrender at Appomattox to Jane Addams’ Twenty Years at Hull-House. Students read a short, descriptive excerpt and interact with it somehow: by outlining or drawing main points, writing a statement agreeing or disagreeing with it, characterizing its tone.

Pros: Students see that a textbook is not the ultimate commentary. They hear real people’s voices leaping off the page.

Cons: This is a highly teacher-directed activity that relies on our determining which sources are most vivid. Conversely, if we ask students to find original documents without enough guidance, some readers might find the sources incomprehensible.

- Supplement a Historian’s Argument: Choose bits of documents that show students how a historian arrived at his or her conclusions.

Starting with the second week of the emancipation course, I followed this pattern, first reading the secondary source as an overview and then filling in with primary sources. The process was much less frustrating than the first week’s reverse order.

Pros: Students see the complexity of how historians create big ideas, which might inspire them to have more patience as they construct their own research and arguments.

Cons: This could take a lot of class time, which may or may not be appropriate. If the goal is to show students how historians craft arguments, several days would be worth it. If the goal is to have students understand how important Madison’s guidance was to the delegates, a more direct approach might be better. Also, if we use this approach, we lose some of the mystery of beginning with a mess of primary sources and then working toward a conclusion.

Why is a primary source important?

For our students, it seems that the best question we can ask is: Why are we spending time on this source? Is it for the language, argument, sense of place, chronology, or something else? Once we have the goal in mind, we can decide on timing and methods.

What I’ve remembered most from reading primary sources this summer are the visceral moments – when I was surprised, as with Dred Scott, or challenged, as with the first week’s readings on military and legal emancipation.

Surprise and challenge: not a bad place to begin.

Sarah Cooper teaches eighth-grade U.S. history and is co-dean of faculty at Flintridge Preparatory School in La Canada, California. She lives just outside Los Angeles with her husband and two sons, both in elementary school. She is the author of Making History Mine (Stenhouse, 2009) and Creating Citizens (Routledge, 2018). Sarah writes and reviews books for MiddleWeb.

Great post. For more ideas for teaching with primary sources plus loads of curated primary source sets from the Library of Congress, check out the TPS-Barat Primary Source Nexus teaching resource blog: http://primarysourcenexus.org/

What a rich compendium of sources and ideas! Thanks for linking.