A Great Resource for Quality History Lessons

A MiddleWeb Blog

As teachers, it is often difficult to find a balance between self-created, district-created, and program specific-created materials that we use in the classroom.

Most teachers I know use a combination of these kinds of resources to flesh out their students’ experiences in content. Personally, I have had the option to create most of my own resources – collaborating with my fellow MiddleWeb bloggers Shara and Aaron. But there are times when it becomes obvious that reinventing the wheel may not be the best move to make.

I found this to be true at the end of the last school year when I was pressed by many other responsibilities, as we often are. So I wondered, with limited time, what would be the best way to have my students explore Reconstruction?

I teach 8th grade American history, and I truly didn’t think my students’ understanding of the Civil War would be “complete” if we stopped with the war itself. The standards agree with me. Arguably, what happened afterwards was as important to shaping our current country as the war itself.

A super free resource

How could I involve my students in the post-war period in a short period of time? I asked Twitter and, thankfully, SHEG — the Stanford History Education Group – replied that I should try their inquiry question on Reconstruction.

If you sign up for SHEG (it’s free), you have access to all of the lessons they have available for the middle grades – both content based and process based. The lessons are all inquiry based; they are often structured academic conversations with a foundation in primary source documents.

While I have been a constant lurker on the SHEG site, I hadn’t yet done one of their lessons as written. So for the first time, I tried one. (Click on the title icon below to download the lesson plan, supporting documents and handouts, the organizer, etc.)

The question revolves around this idea: Were African Americans free during Reconstruction?

Using primary source documents and a timeline, the students are guided to use evidence to argue for or against the state of African American freedom during the time of Reconstruction.

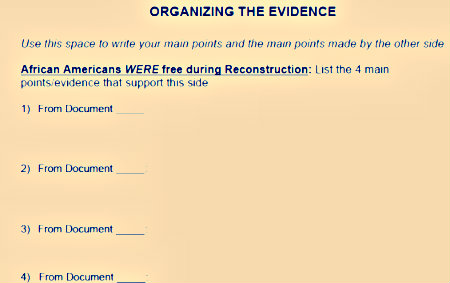

In pairs, and using the graphic organizer below, students close-read the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments, the Black Codes of Opelousas, Louisiana, and assorted primary source narratives, and then create the argument for their side.

What I noticed at this stage was that some students arguing that African Americans were free during the time of Reconstruction were uncomfortable, because they personally didn’t agree with the statement. This was a great learning experience for them, because the SAC (structured academic conversation) requires students to argue regardless of passion and collect evidence that might be contrary to personal belief to create an argument for the “other” side. It is a strong academic lesson.

These students’ own beliefs were not stifled by the SAC because the closure discussion allows the students to abandon the argument they’ve carefully constructed in order to express their true thoughts on the question – albeit thoughts that are more nuanced, given their increased understanding of the complexity of the situation.

After creating the argument and organizing the evidence, students then share with a pair who have been creating the opposing argument. My class is organized in teams of four, so it was easy to do this initial pairing then subsequent coupling of the pairs.

The structure of the conversation is paramount here. Students take turns offering their evidence and the other team listens, taking notes about what they are hearing. Then, and this is key, the listening team shares back what they heard and the presenting team either confirms or re-explains.

This procedure is great, because the structure requires the students listening to be really present while the other team is speaking. Because they are invested, their impulse is to protest and counter with their own evidence, but the structure stops them and requires them to limit themselves to gathering information.

A nuanced, evidence-based understanding

Finally, in my class, students discussing the Reconstruction question were allowed to abandon their positions and argue for what they really believed. But as I said above, the arguments now were more nuanced, rooted in evidence, and contained more complexity than they would have otherwise.

The lesson concluded with a whole group discussion. The students wanted to share their understandings of the topic, but also to take it further and discuss the implications of Reconstruction on the present day–and whether, ultimately, it was a success or a failure.

I am, like many people, both a fan of structured conversations and also wary of their parameters. However, my students thrived on the structured part of the academic conversation.

Monitoring their conversations, I was thrilled to see the students so engaged. The collaborative aspect allowed them to talk through their ideas, but the size of the initial groups–just two students–required both to engage with the material, and no one was able to disappear within the workings of a larger configuration.

The structure required an engagement with the text that was rooted in an important outcome–the conversation they would have “proving” their point to the other side–and this motivated them.

Once the positions were abandoned, it was nice, too, to see the students able to negotiate between their own views and the understandings they had gleaned from the primary source documents. Many groups came to consensus about the question.

So what is the takeaway here?

For me, part of the takeaway is that, sometimes, I need to let up a bit on my control and my need to feel like I’ve created the thing that we are going to do in class today. It is OK and sometimes even great to use created materials for class – like SHEG’s lessons and other resources. I know many history teachers use DBQ (Document-based questions) and there are other programs out there to discover. From my perspective, clearly my students would benefit!

What are some pre-written lesson programs you’ve tried for history in the middle grades? What were your takeaways?

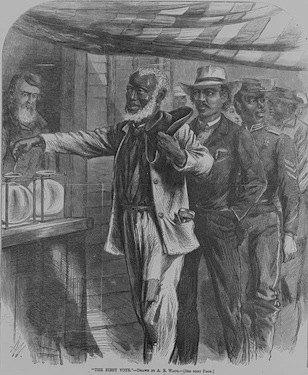

Image Credit: 1st Vote for African Americans: Waud, Alfred R. (Alfred Rudolph). “The First Vote.” Nov. 16, 1867, from Harper’s Weekly. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

TregoED.org offers a free online discussion tool that offers a whole library of lessons plus you can write your own. The discussions are guided by their SCAN critical thinking strategy, four questions: See the issues, Clarify, Asess, Now, what should be done? Students discuss the issue from 4 different perspectives. Lessons on the Boston Tea Party,Women’s vote, school based lesson on the Bill of Rights (Locker searches, T-shirt controversy, etc.). Links are provided for evidence based searches (or you can add your own!). Free, no hitches.