A Culture of Thinking Can Transform Schools

Creating Cultures of Thinking: The 8 Forces We Must Master to Truly Transform Our Schools

By Ron Ritchhart

(Jossey-Bass, 2015 – Learn more)

Reviewed by Mary Langer Thompson

Reviewed by Mary Langer Thompson

“Culture is the key to transformation,” says Ron Ritchhart, and anyone interested in seeing lasting change in schools needs to read this book. Don’t expect an easy read, however. It’s not a jiffy checklist.

What is culture? Here it’s defined as a group of people enacting a story, with everyone a player, so we need to take a hard look at the story of learning we’re telling, and the messages we’re sending. The starting point is to send a message about the value of thinking. We must also, Ritchhart believes leverage 8 cultural forces: expectations, language, time, modeling, opportunities, routines, interactions, and environment.

What is culture? Here it’s defined as a group of people enacting a story, with everyone a player, so we need to take a hard look at the story of learning we’re telling, and the messages we’re sending. The starting point is to send a message about the value of thinking. We must also, Ritchhart believes leverage 8 cultural forces: expectations, language, time, modeling, opportunities, routines, interactions, and environment.

Chapter Two discusses how we need to focus students on learning, not work. Research shows the brain literally grows as a result of learning. If our culture is learning oriented, teachers are more likely to give students choices and mistakes will be seen as opportunities to learn and grow.

Language and its effects

I especially like how Ritchhart, a senior research associate with Project Zero at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, shows how our language and metaphors reveal our beliefs.

For example, the work metaphor has been popular in schools for years. Think of the vocabulary we use: The principal is the “Chief Academic Officer,” we need to have “time on task,” we want to instill good “work habits.” In one study, “work” was used 49 times more often than “learning.”

Chapter Three goes even deeper into an analysis of language and its effects. Ritchhart introduces a teaching routine called “See-Think-Wonder.” In one lesson, the teacher shows a photo and asks what might be going on. He talks about how what we notice and name tells what we value. Too often, he says, we teach about a subject rather than engaging students in it. He talks about the language of praise and feedback and what deep listening can do.

Finding time

Time is another force we need to master to transform schools. The author observes a 12th grade class in Australia and notices how the teacher builds relationships. This teacher also uses Individual Feedback Sessions (IFS) and gives up breaks and meets with students after school.

Again he quotes a study, one that shows that time pressure diminishes creative responses. Both teachers and students need time to think and reflect. We can do this by managing our energy rather than time. Even adults need to build in moments to recharge their energy by, for example, taking movement breaks.

Modeling

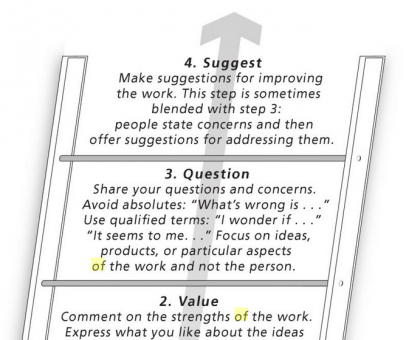

Another force is modeling, showing students what learning and thinking look like. Natalie wants to be seen as an authentic, honest, and genuine teacher. She shares personal stories, her own journal entries, does “think alouds,” and then teaches her students to write poems. We see the kinds of questions she asks. The author quotes Sizer (2000): to understand a school, its core, “Look at the way the people in it spend their time, how they relate to each other, how they grapple with ideas.” The “Ladder of Feedback” in Appendix B is worth the price of the book to use as a tool.

Teaching less, routinely

Chapter 6 alone has more ideas many will find revolutionary. “Teaching less” is one of them, and Ritchhart believes if we are giving students the right opportunities to think, standardized test results will take care of themselves. He discusses a pyramid of opportunities from “moments” to “events” which connect to the larger community. Students have to see these opportunities as worth their time, and teachers need to step back from center stage and have students do more of the work.

Chapter 7 discusses the importance of routines and tells how the author models a math lesson to kindergarteners who are already used to “Think, Pair, Share” and questioning routines. More on this topic is shared in the author’s previous book, Making Thinking Visible.

Warm demanders

Interactions are crucial because learning is social. The author is blunt: “Kids won’t learn from those they don’t like.” Teachers need to be “warm demanders.” The teacher can begin in the center, but needs to gradually withdraw. The author gives some strategies like literature circles and book clubs. Learn how teachers should avoid “popcorning” for “ice-cream-coning.” Students can even begin examining conversations (“unrehearsed intellectual adventures,” Oakeshott, 1959) to see if people are “ping-ponging” or passing the ball, as in basketball.

Chapter 9 talks about the importance of environment and using space to support learning and thinking. This chapter should be at the beginning since classroom seating and furniture arrangements would be the easiest way to foster interaction and thinking and some teachers could begin the year in a new way.

Sir Ken Robinson is quoted: “If you want to shift culture, it’s two things: its habits and its habitats—the habits of mind and the physical environment in which people operate.” Environment is a third teacher, and the teacher is a curator. Although the author would like to see whole schools designed without “cells and bells,” that would take someone in authority sitting down with the architect before construction.

A brilliant call for systematic change

Ritchhart admits there is no single blueprint to transform a school into a culture of thinking, but he gives suggestions for starting and ends with the metaphor of a gardener planting seeds. He adds letters from a superintendent, a principal, a Visible Thinking Coordinator, and others. There are thinking rubrics in the appendices.

This book is a brilliant analysis of what we need to transform schools, but I felt overwhelmed reading about all the ways our schools need to change. He is asking for a systemic change in our approach to learning. I recognize and could point to single classrooms where one or two of these forces are at work, but sadly no districts or even whole schools.

I agree these changes are what we need, but first we’re going to have to change the thinking of teachers and administrators. A start could be to get this book into the hands of every education professor and every superintendent and principal, not to promote top-down change, but to start system-wide conversations about these eight forces.

Dr. Mary Langer Thompson’s is the author of Poems in Water, her first collection of poetry. She is a retired school principal and English teacher who still teaches writing workshops in schools and believes that writing is thinking.