How We Learned to Love Writing Together

This story by Ruth Ayres, from her new Stenhouse book Enticing Hard-to-Reach Writers, is a holiday gift to novice educators everywhere and to any teachers still wondering whether their students can ever learn to love writing.

It’s my first year of teaching, and our staff is reading Harry Wong’s book The First Days of School (2004) and watching his video series. In the very first pages of the book, Wong describes the following stages of teaching: Fantasy, Survival, Mastery, and Impact. He cites Kevin Ryan, who conducted research about these phases of teaching and concluded that most teachers never make it past the Survival stage.

I laugh along with my colleagues as we watch Wong describe the Fantasy stage in one of his videos. Two weeks into the school year, I’m thinking, “No way am I in Fantasy. I love my job and love building relationships with students. I just know what a great job it is.” (It’s okay for you to smirk right now; I’m smirking as I write this.)

A few weeks later, my desk is piled high with stacks of papers and I’m wondering why there were so many incomplete assignments when I realize that I’ve left the Fantasy stage and entered Survival. I’m staring at a workbook for a basal reading series, looking for something to keep my students busy and me sane, when my mentor, Tam Hess, finds me.

“I just saw this flier about a study group about writing instruction. Do you want to go?”

“I just saw this flier about a study group about writing instruction. Do you want to go?”

Wild-eyed, I look up from the worksheets. “My students won’t write. I have so many incomplete writing assignments; I don’t even know what to do.”

“I don’t know if this study group will help with that,” says Tam, “but we get a free book and there’ll be snacks. I talked with the principal and he said we can leave school early in order to make it to the study group on time. Do you want to go?”

No magic

I look down at my desk and run my fingers across a sticky note on which I’d written a line from Wong’s book: Effective teachers strive for Mastery by reading the literature and going to professional meetings. (I wish I could say it’s the drive to reach Mastery that persuades me to say yes, but in reality it’s the free book and snacks.)

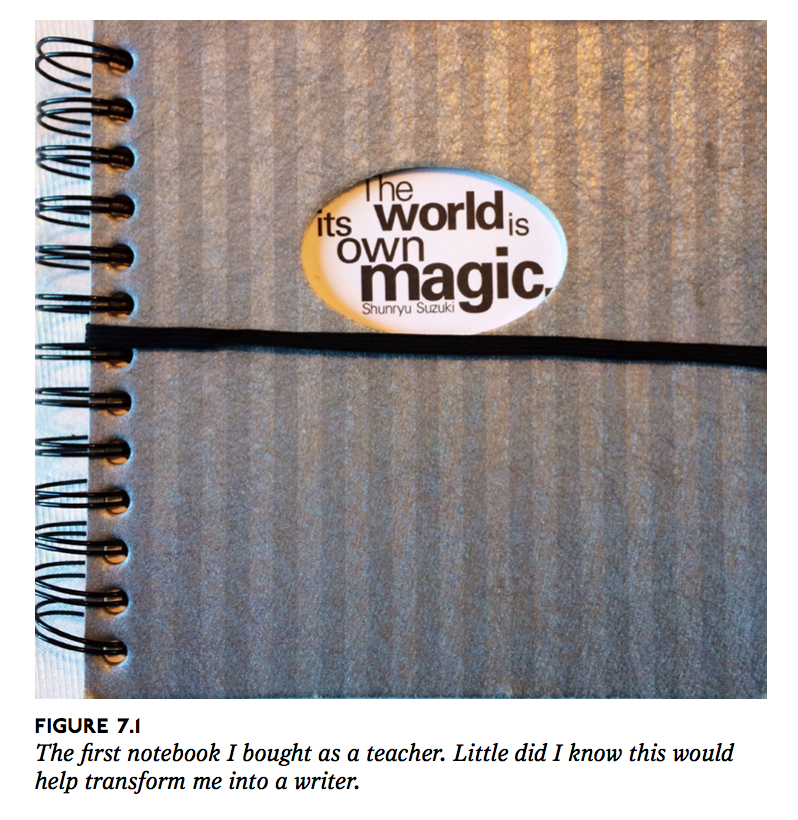

We’re supposed to bring a notebook to the meeting, so I grab one that I bought before school began. I look at it and feel like crying. I wish I were still in Fantasy, I think.

The quote on the front makes me sigh. There is nothing magical about my classroom. Nothing. It is all I can do to survive each day.

The quote on the front makes me sigh. There is nothing magical about my classroom. Nothing. It is all I can do to survive each day.

The teachers at the meeting are gathered to discuss something called “writing workshop” that they use in their classrooms. It sounds like utopia to me. Teachers deliver a little lesson and then give students time to write. The meeting participants discuss how their students choose their own topics and fill page after page with their own ideas. Participants tell stories about students sharing their writing and entire classes erupting in applause.

I’m skeptical. My students won’t even write on the topics I give them. I can’t imagine the mass chaos that would ensue if I gave them twenty to thirty minutes to write about anything they wanted. My students hate writing. I know because they tell me. Daily. Loudly. Emphatically.

During the meeting, we are asked to do a quick-write on whatever we want—we just have to write for the entire allotted length of time. No thinking, just writing. “This is a great way to get your students writing because it frees them from the stress of getting it right,” says one of the leaders.

I try not to roll my eyes. If I were to try this in my middle school classroom, my students would probably draw all over the pages.

The timer is set and we start writing. I write on a scrap sheet of paper instead of in my notebook; I don’t want a record of what I’m feeling. My entire vision of what it means to be a teacher is being shattered. Maybe I completely missed my calling. Maybe I’m doomed to be a failure.

The timer is ticking and everyone around me is writing.

And I remember: I used to want to be a writer. Why not write? If I’m going to fail as a teacher, maybe I can at least use the time to learn to be a writer.

I begin putting words on the page. I don’t realize that with each letter, each word, each sentence I am stepping out of Survival and becoming a teacher of writers.

The timer goes off and a few people share their writing. Then the people running the meeting give us a book: Clearing the Way (1987) by Tom Romano. Between the covers, I meet a teacher-writer who has respect for students and their writing. I learn about writing process in theory and in practice. I realize the power of writing to learn and discover. I find footing for evaluating and grading. The free book gives me the freedom to learn how to meet the needs of the young writers in my classroom.

But I’m still not a believer. After all, Mr. Romano has never set foot in my classroom full of disengaged writers. Mr. Romano’s students want to write. Mine want to sleep.

Surfacing

I suddenly decide, Why not? Whining and lamenting isn’t making a difference. Instead of just taking the bits and pieces from Romano’s book and from the meeting, why not take it all? Why not give this workshop deal a whirl? If it flops, I’m only losing one unit of instruction, and besides, it really can’t be any worse than what’s going on already.

I spend all day Sunday making 125 notebooks by stapling blank copy paper together. (Why should I invest in notebooks when this whole thing is obviously going to fail?) The next day, I pass out the notebooks and have the students decorate their covers.

“You are going to be a mystery writer,” I tell them, “and you need a notebook to help you collect ideas for your story. Take some time today to make a cover that will inspire you.”

The kids stare at me. I point out the colored pencils and markers and crayons around the room. I direct students to the piles of magazines on the back table and the scissors and glue sticks. I hold up the notebook cover I made late the night before.

“You can’t do this wrong,” I say. “Just collect some words or pictures that will inspire you to write.”

They start moving. Soon there’s a buzz in the room as students talk about ideas. It isn’t chaos. It isn’t loud. B.J. isn’t dancing on top of the desks. Students are working with their notebooks and sharing ideas for possible mystery stories.

“Beginner’s luck,” I tell Mrs. Hess in the hallway after school.

Red herrings

Now that we have notebooks, we have to figure out how to write a mystery. I collect some short mystery stories, provide a quick summary of each one, and leave copies of them in folders on the back table.

“Select one to read and then figure out what makes it a mystery. Then read another.” In the name of trusting students as writers, I decide not to be bossy. They can decide what texts to read and how to keep their thoughts to share.

The kids are as engaged as they were while making their notebooks. I pinch myself to make sure I’m not dreaming. My students always avoid reading.

Near the end of workshop, we gather around a piece of chart paper. I write a question at the top of the chart: What do we need to write a mystery?

“What did you notice about the mysteries you were reading? What did they have in common?” I ask.

Instead of heads down and dead silence, the students jump into a conversation. We make a list:

Characters

A creepy place

A problem

Lots of people could have done it

“I think we should say ‘suspects’ for that one,” I say. The students nod in agreement. I make the change and ask, “Anything else?” They continue the list:

Talking

Smells and sounds

Clues

An ending that solves the mystery

“I’m thinking about clues,” says Jami.

I’m intrigued that even though the list goes on, Jami brings us back to clues. “What about them?” I ask.

“I don’t know. Just that . . . well, I guess . . . they didn’t always point to the guilty person. They make you think someone else did it.”

“I don’t know. Just that . . . well, I guess . . . they didn’t always point to the guilty person. They make you think someone else did it.”

“Red herrings,” Zach says.

Everyone looks to the back corner of the room. I’m not sure what’s more shocking: that Zach is awake, that he’s talking, or that he’s spot-on.

“What are you talking about?” Jami asks.

“Red herrings. That’s when there’s a clue that makes you think someone else did it. The best mysteries have red herrings so they’re not too easy to solve.”

As the bell rings, I add “red herrings” to the list.

“It’s over already?” I hear someone say as students gather their books. “This class went fast.”

It’s been another successful day. Once again, I chalk it up to beginner’s luck.

The tide turns

As students fill their notebooks, more and more successful days go by. My notebook is filling up, too. It’s the only way I can figure out what to teach—I have to do the work as a writer in order to help students write.

I always thought writing a mystery story would be easy. I soon realize that I can add that idea to the growing list of all the things I thought about teaching that would prove to be untrue. I spend hours in my notebook, not only writing, but also trying to figure out what I’m doing as a writer so I can bring it to the classroom.

This is where the tide of mass disengagement turns. When I show students my writing, I have their full attention. When I admit my struggles with figuring out the story, they are willing to try to sort through their own plots. When I register excitement because I figure out how to make action, thinking, and talking work together, it permeates the room and soon most students are trying the same thing.

At the end of the unit, every single student turns in a mystery story—compared to forty-eight percent for the previous writing assignment. Even an English teacher can understand the significance of those statistics!

___________________

Ruth Ayres has been a middle school teacher and instructional coach and currently directs a professional development consortium in northern Indiana. Ruth is the co-author of Day by Day: Refining Writing Workshop (with Stacey Shubitz) and Celebrating Writers (with Cristi Overman).

Ruth Ayres has been a middle school teacher and instructional coach and currently directs a professional development consortium in northern Indiana. Ruth is the co-author of Day by Day: Refining Writing Workshop (with Stacey Shubitz) and Celebrating Writers (with Cristi Overman).

Her new book Enticing Hard-to-Reach Writers (Stenhouse 11/2017) “explores the power of stories to heal children from troubled backgrounds and offers up strategies for helping students discover and write about their own stories of strength and survival.”