Stop Boring Nonfiction Writing. Save the World.

or Why Writing Interesting Nonfiction Text is Critical for Our Students and How to Help Them Get There!

By Angie Miller

So many of my Sunday afternoon essay-grading sessions have been spent in self-negotiation: Watch one Netflix show after every 15 papers. Change over the laundry after this one. Go for a run halfway through. Eat dinner with my family after this class’s stack. Save So & So’s paper for later as a reward. Anything to break up the monotony, because I am bored. Bored. Bored. Bored.

And then, one day, in the middle of reading through thirty-eight uninspired 8th grade essays about the Medieval Period, I got tired of my self-imposed, self-designed head games. I set the stack aside and made a resolution: no more boring writing.

I showed up to class and handed the papers back to my 8th graders. “Um,” one of them ventured. “There’s no feedback on these.” She looked at me hesitantly. “Nope,” I responded. “No feedback at all. Because we’re starting over.”

Silence met me. I took a deep breath and met their on-the-verge-of-rebellion eyes.

“You guys,” I dared. “These are boring. SO boring!” My confession fell out of me to complete silence. They stared at me.

“But,” I continued. “I’m not blaming you. I’m blaming myself. I’ve never asked you to write in an interesting way. I’ve never helped you develop those skills. So, I’m not saying they are boring because of you – I’m saying we just haven’t worked on this together. So we are starting over, and I’m going to help you write something interesting.”

Lily raised her hand. She was a straight A student who had her long-term wishes on Harvard – she was one of my best writers. “Thank you,” she said. “My writing is so boring I don’t even want to proofread it. If I don’t want to read my own words, why would anyone else?”

Exactly.

Readers crave interesting writing

As readers we crave voice – we long for rich words and images to climb off pages, nestle into our minds, and engage us in their dance. We like to taste language. We greedily wrap ourselves around text and keep it to ourselves.

As readers we crave voice – we long for rich words and images to climb off pages, nestle into our minds, and engage us in their dance. We like to taste language. We greedily wrap ourselves around text and keep it to ourselves.

But as teachers we often find that showing students how to integrate such voice into their own nonfiction writing feels like an insurmountable task. We silently admit to ourselves that good writing comes intuitively, and that some students are just better at it than others. And instead of teaching our students how to write something interesting, we focus on content and conventions while implicitly letting them know that academic writing is synonymous with boring writing.

However, boring writing doesn’t get noticed. It doesn’t make change; it doesn’t get us into college or get us a job. Boring writing conforms our voices so that our ideas fall into step and sound like everyone else’s. Boring writing is dangerous because it ultimately silences us into anonymity.

Asking our students to write well is one thing. But asking them to write exquisitely is infinitely more important. Because, like Lily pointed out – if nobody wants to read a piece of writing, how effective will it be?

Teach like a writer. Have kids read like writers.

We all know good writing when we read it. Like a stunning piece of art that takes your breath away or a piece of music that energizes you, good writing is often difficult to name. But it is not impossible.

We all know good writing when we read it. Like a stunning piece of art that takes your breath away or a piece of music that energizes you, good writing is often difficult to name. But it is not impossible.

Just like students can be taught to examine the convergence of color in a painting or the pairing of a violin and cello in a crescendo, they can also be taught to recognize the cultivation of sentence structure, the magic of precise language, and the intricate balance of information and narrative. They can read expository writing that enchants them while critically examining how the working cogs of an essay propel it forward.

But this takes a shift in instruction: instead of teaching our students to read like readers, looking at content and comprehension, we need to show them how to read like a writer. And for us to do that, we have to also teach like a writer. Here are some strategies:

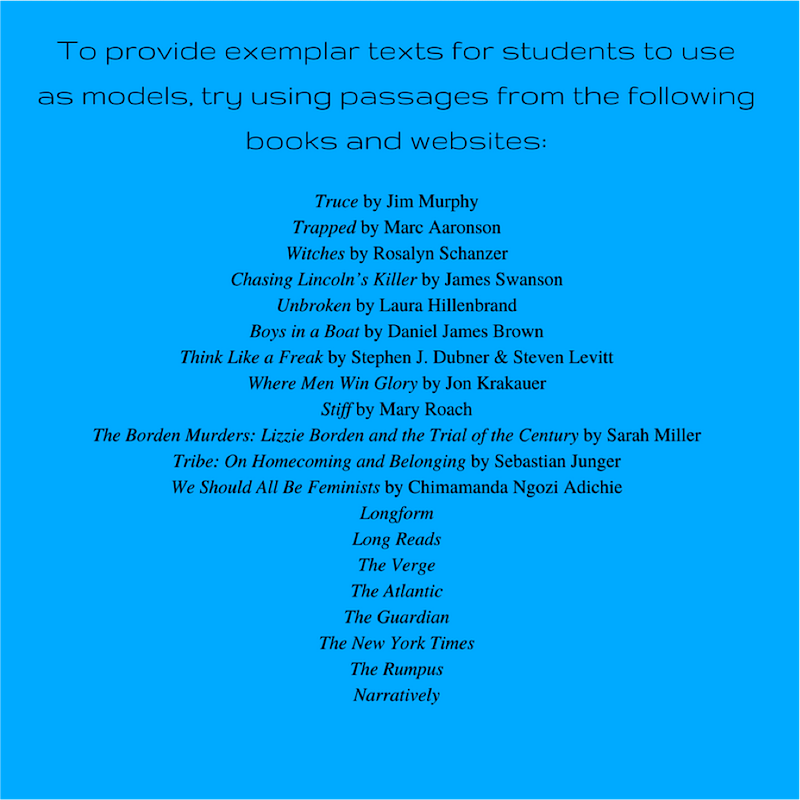

- Use compelling mentor texts (see a list of suggestions below) as exemplars and ask students to identify the strategies used.

- Model those strategies in front of students in your own writing – be flawed and purposeful. Write with your students!

- Avoid formulaic writing – five paragraphs doesn’t provide structure; it limits student voice.

- Ask students to look at pictures and photographs of what they are writing about to better include imagery in their writing.

- Provide opportunities for students to write for authentic audiences.

- Show students the importance of precise language: vivid verbs and specific nouns, in particular.

- Give frequent and meaningful feedback throughout the writing process

Does it work?

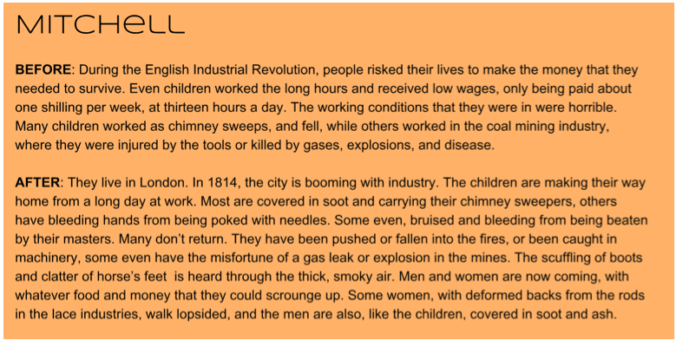

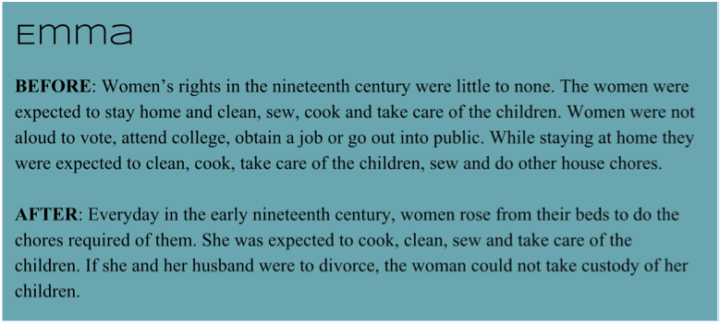

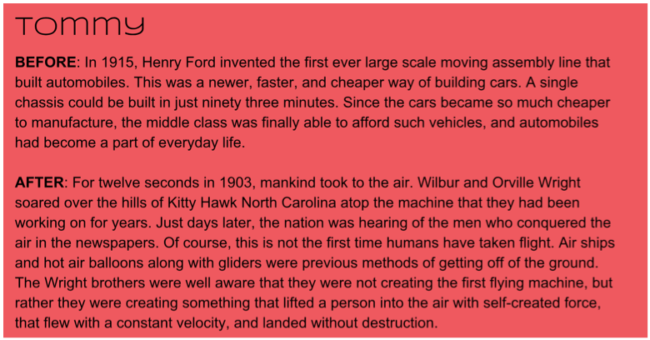

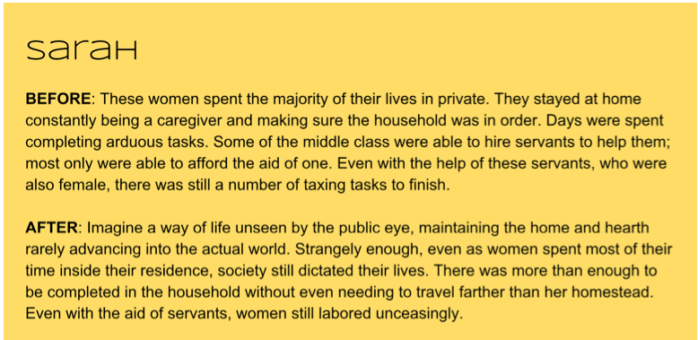

Yes. Take, for example, these before and after early revisions from a 19th century research project a group of my 9th graders worked on. For each one you will recognize intentional revision to word choice, imagery-integration, sentence structure, and order of information provided. Instead of simply setting facts into ordered sentences, these students were learning how to engage their readers in a topic that they were fascinated by. (Click to enlarge.)

What next?

This year, as you head back into the classroom, emphasize the importance of writing that comes alive to your students. Give them tangible means to make that happen. Explicitly break down pieces of nonfiction writing alongside them. Shift the writing conversation so that they are cognizant of meaningful revision. When we do this, our classrooms will become places where students are empowered by their own voices. I promise they will return and thank you for allowing them to develop a voice.

______________________________________

______________________________________

Angie Miller is the author of It’s a Matter of Fact: Teaching Students Research Skills in Today’s Information-Packed World (Routledge, 2018). A middle and high school teacher-librarian, Miller was the 2011 New Hampshire Teacher of the Year.

She is also the recipient of the 2017 New Hampshire Library Program of the Year award and has been a TED speaker and a National Geographic Teacher Fellow. Follow her on Twitter @angieinlibrary.

It’s a Matter of Fact is co-published by MiddleWeb. For a 20% discount, use the code MWEB1 during checkout at the Routledge website.

Here’s an interesting mentor text for not-boring writing that librarians and other book lovers will… well, love!

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/librarian-detectives-forgotten-books

“THE CARPET WAS KHAKI, THE lights yellow, the walls a dishwater beige. The basement computer lab in Midtown Manhattan didn’t have much ambience. But 20 librarians from the New York Public Library were seated in the room—and they were there to crack mysteries….”

Read it before sharing with students… there are a few places that might need redacting.

Angie, this is a wonderful article. The student examples you give really shine. How much of a mentor text do you tend to use as a model, and how long do you tend to spend on it? I am even more inspired to use excerpts from “real” history books this year to encourage strong writing.

Hi Sarah–thank you so much! I do short excerpts–a paragraph at a time, and I choose ones that target the skill I want them to work on, so it might be a passage that has great active sentences or one that uses narrative voice or one that combines a bunch of typically-boring facts into something engaging (I read one with my seniors this year on why English is so difficult to learn–it was full of information on root words and grammatical structures and could have been incredibly dull, but the word choice made it super interesting!). We focus on just that paragraph (for my older students, I might do an entire essay–depending on focus & length).

Jim Murphy (my kids say they’re gonna “Murphify” their writing when they start revising) & James Swanson are just brilliant history authors. The kids *love* the scene from Chasing Lincoln’s Killer where he slows the ball down and dissects it as it enters Lincoln’s brain.