Teaching Visual Literacy: Images and Propaganda

Throughout history, images have been an important part of the media message. They’ve also been a part of the education curriculum. Since the invention of photographic printing, pictures have routinely accompanied the words written about critical events in social studies textbooks.

Throughout history, images have been an important part of the media message. They’ve also been a part of the education curriculum. Since the invention of photographic printing, pictures have routinely accompanied the words written about critical events in social studies textbooks.

And students today rely on images to help “tell the story” – just as much as (if not more so) than the words.

Iconic images from history come to mind: the 1937 crash of the Hindenburg airship; baseball great Lou Gehrig’s “luckiest man” speech in 1939; Franklin Roosevelt’s “Day of Infamy” speech to Congress in 1941; emaciated prisoners of the just liberated Buchenwald concentration camp in 1945; Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the Moon (1969); the fall of the Berlin Wall (1991) and many others.

Ask your students what image comes to mind when you mention one or more important events in world or American history. (Also: In an earlier MiddleWeb post, I wrote about how images become iconic.)

It’s not a simple matter to separate photojournalism from visual propaganda (designed to evoke emotions and sway political opinions). Was the iconic image of a fatally wounded college student during the Kent State protests in 1970 intended to report facts or influence national policy? It surely did both. (Did you know the photo was “doctored” before publication to remove a fencepost behind the central figure?)

“Purpose” often depends on the context in which an image appears. Consider the career of Dorothea Lange.

Dorothea Lange and the Migrant Mother

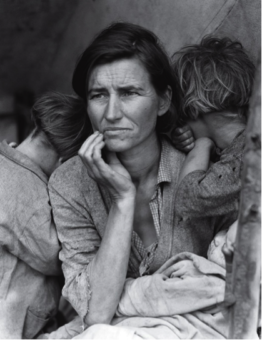

In 1936, documentary photographer and photojournalist Dorothea Lange (pictured left) was on assignment in California. She saw a sign on the road and stopped her car at a migrant farm workers’ camp. She took a series of pictures of Francis Owens Thompson and her children. (Lange said she never asked the mother’s name.)

In 1936, documentary photographer and photojournalist Dorothea Lange (pictured left) was on assignment in California. She saw a sign on the road and stopped her car at a migrant farm workers’ camp. She took a series of pictures of Francis Owens Thompson and her children. (Lange said she never asked the mother’s name.)

Lange sent the images and a brief description to her boss, Roy Stryker, at the federal Farm Security Administration (FSA). The goal of FSA was to improve conditions and resources available to farmers. (Stryker and the work of FSA photographers is examined in this PBS documentary.)

Little did Lange know that one particular image from her “shoot” at the peapickers’ camp was about to make her famous.

The photo became known as “Migrant Mother.” TIME magazine later included the image in its 100 Most Influential Images of All Time. Lange was not working in a journalism capacity at the time she took the California migrant images, but 21 of her photos were included as part of an article by John Steinbeck in the San Francisco News.

Students could consider:

- What might the expression on the woman’s face reveal?

- Why do you think her children did not look at the photographer and her camera?

- How does this image make you feel?

Your students could conduct a visual literacy analysis by asking them to list everything they see in the photograph. What can they infer? What do they want to know that they don’t already know? Where can they go to find more information?

Twenty four years later, photographer Lange wrote about how she came to take the picture:

I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet,” she recalled in 1960 interview with the magazine Popular Photography. Thompson had just sold the tires from their car in order to purchase food for her family. “I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her but I do remember she asked me no questions. There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her,” Lange recalls, “and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.”

When the “Migrant Mother” photo was published in a San Francisco newspaper and when readers there and elsewhere saw it, they wrote to Congress, petitioning the federal government to send food to the starving workers. Food was delivered, but by the time it arrived, the mother and her children had moved on. (More about Thompson’s life before and after the image appeared in this Antiques Roadshow article.)

Great Depression and New Deal imagery

Lange took thousands of images during the Depression, and she was just one of a number of photographers who were sent around the United States to document living and working conditions after the Great Depression and in the years before, during, and after World War II.

Lange’s caption: “Migrant cotton pickers at lunchtime. Near Robstown, Texas.” (1936)

Some photographers were on assignment as part of Franklin Roosevelt’s effort to build support for New Deal programs that began in 1933. (All of the images taken are available online for students to access, evaluate and study.) I previously wrote about another FSA photographer, Gordon Parks, who later became a photojournalist for LIFE, covering the civil rights era, and eventually a Vogue photographer and Hollywood director (Shaft). Read his FSA story here.

Was the FSA’s purpose simply to create an historical record of farm life in America? This writer at Boston University asked the quintessential question: “(were the photos) simply information, a mirror in which America could have a look at itself, or did it constitute propaganda?”

Ask your students some of these questions:

- What is propaganda?

- Can the same photograph be used as propaganda and as ‘pure’ reporting? (Can they cite other examples?)

- What was the mission of the FSA photographers? Did they adhere to the mission or stray from it?

- Did the photographers themselves believe they were on a “propaganda” mission or something else?

- Did President Roosevelt see the images as helping get political support for “The New Deal”?

- Did the FSA photographs result in “social change”? (What was Lange’s conclusion?)

- In what ways is photography being used today to document people and conditions we might not be aware of? Locate examples.

Dorothea Lange later documented conditions at the Japanese-American internment camps during World War II (the bulk of her imagery taken for the War Relocation Authority was withheld until after the war). Her WRA work there is described in this brief National Archives video and in more detail in the book Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment.

Lange’s caption: May 8, 1942 — Hayward, California. Members of the Mochida family awaiting evacuation bus. Identification tags are used to aid in keeping the family unit intact during all phases of evacuation. Mochida operated a nursery and five greenhouses on a two-acre site in Eden Township. He raised snapdragons and sweet peas. Evacuees of Japanese ancestry will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration. Source

Lange’s caption: May 8, 1942 — Hayward, California. Members of the Mochida family awaiting evacuation bus. Identification tags are used to aid in keeping the family unit intact during all phases of evacuation. Mochida operated a nursery and five greenhouses on a two-acre site in Eden Township. He raised snapdragons and sweet peas. Evacuees of Japanese ancestry will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration. Source

Image literacy is important

Today’s students are part of an increasingly visual world. Images in textbooks, in the news, and elsewhere are perfect teachable texts that can be engaging and thought-provoking for tweens and teens. They also have potential as part of lessons that emphasize social-emotional learning and empathy.

When teachers take the time to introduce students to historical images, and the photographers who captured them, we are once again satisfying many of the goals of American education.

Teaching students to read, analyze and deconstruct visual images is a huge part of visual literacy education. I hope you will consider the ideas and resources I have shared here.

Resources Worth Exploring

► Dorothea Lange’s story is told in the PBS documentary “Grab A Hunk of Lightning.” A recent museum exhibit, The Politics of Seeing, showcases Lange’s work and the impact it had.

► I Am…Dorothea Lange: Exploring Empathy Art Lesson (Art Class Curator) – created by a middle school “art-on-a-cart” teacher.

► Migrant Mother: Documenting American Life in the 1930s Through Photography (PBS) – A self-paced lesson for upper middle and high school. Notice other related lessons in the right-hand column for grades 4-8.

► One-Pager: Analysis of Dorothea Lange’s Photographs (Getty) – A lesson for Grades 6-8 at the Getty Museum site.

► Teaching Media Literacy: “The Grapes of Wrath” – Lange’s work certainly influenced the filmmakers involved in 1940’s The Grapes of Wrath, John Ford’s interpretation of the Pulitzer Prize winning Dust Bowl novel by John Steinbeck, which figured prominently in Steinbeck’s selection for the 1962 Nobel Prize for Literature.

____________________________________

Frank W. Baker is the author of Close Reading The Media: Literacy Lessons and Activities for Every Month of the School Year (2017, Routledge/MiddleWeb). He has conducted hundreds of professional development workshops for educators at schools, districts and conferences. He can be reached by email at fbaker1346@gmail.com and on Twitter.

Frank W. Baker is the author of Close Reading The Media: Literacy Lessons and Activities for Every Month of the School Year (2017, Routledge/MiddleWeb). He has conducted hundreds of professional development workshops for educators at schools, districts and conferences. He can be reached by email at fbaker1346@gmail.com and on Twitter.

Another resource worth exploring is Learning from the Source: Zooming into Documentary Photography, which uses Lange’s series of photos of this family. You can find it on the Primary Source Nexus at https://primarysourcenexus.org/2013/08/learning-from-the-source-zooming-into-documentary-photography/