A Tool to Help Students Read a (Resource) Book

A MiddleWeb Blog

Sometimes I’ve been teaching a skill in such a mediocre way for so long that I hardly realize how much better it could be – until something shakes me from my stupor.

Sometimes I’ve been teaching a skill in such a mediocre way for so long that I hardly realize how much better it could be – until something shakes me from my stupor.

For instance, I’ve always known that my students could use actual books more effectively in their research papers – and I do still ask them to use books or e-books, because long-form history can teem with anecdotes and facts difficult to find elsewhere.

But for years, I realized recently, I showed eighth graders how to understand the “bread” of a book – the Table of Contents and the index – without sufficient direction on how to understand the “chicken salad” or “roast beef and cheddar” in between – the actual meat of the chapters.

I felt that students should be able to absorb browsing skills on their own (a sign I wasn’t thinking creatively enough), and I was daunted by asking kids at various levels of reading comprehension to identify a relevant section of a randomly selected book for a research paper.

Inspired by My Colleagues

One day last fall, though, I sat in a history department meeting and had an epiphany.

For the meeting, our department head stacked up a slew of books about the French revolution and asked each of us to choose one. We each spent a significant portion of the meeting looking through our book of choice to see what we could glean from it about the author’s perspective and historiography.

After an intimidating false start in which I realized it would be difficult to deconstruct Alexis de Tocqueville’s views in 20 minutes, I settled on the more accessible Politics, Culture and Class in the French Revolution by UCLA professor Lynn Hunt.

After an intimidating false start in which I realized it would be difficult to deconstruct Alexis de Tocqueville’s views in 20 minutes, I settled on the more accessible Politics, Culture and Class in the French Revolution by UCLA professor Lynn Hunt.

Each of us shared at the end what we had discovered. Even given that we are experts at reading for content, it was impressive how much we could gather about argument and focus in a short time.

At the end of the meeting, I vowed to do something similar with my eighth graders, even though I wasn’t yet sure how it would work.

A Transformative Handout

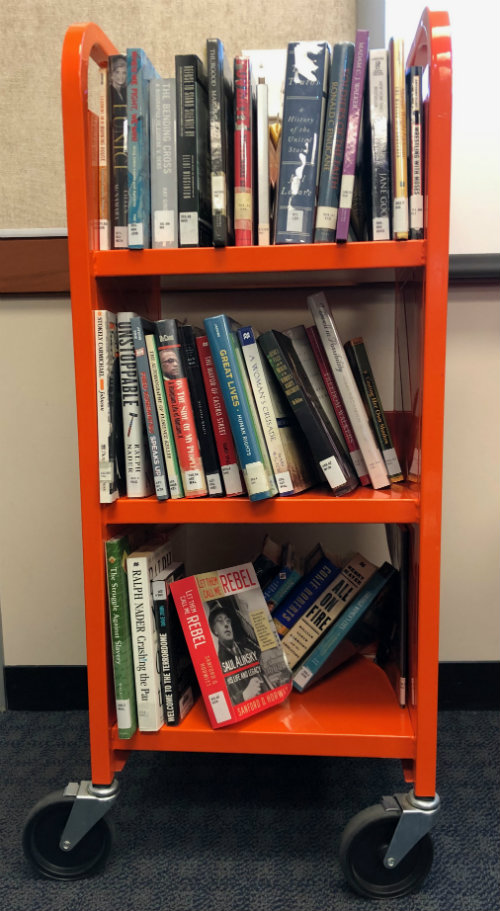

A few weeks before starting a major research project in third quarter, I asked our librarian to put together enough books relating to U.S. reform movements that everyone in the class could glance through one for a period. She far outdid my request, and the resulting cart was a masterpiece of depth and breadth. I pulled it down the hallways to my classroom and couldn’t wait.

Then one Monday just before we started the actual research project, I told the students that “we are going to learn how to read a book for research today.” They would find a book that looked interesting (it was uncanny how many kids picked topics that suited their personal interests) and fill out a two-page handout about what they learned.

The activity started with the basics: title, publication date, author. Then it asked students to cull information about the book from various sources: the introduction or beginning of the first chapter, the index and the table of contents. Take a look:

- Why did you decide to pick up this particular book?

- Let’s get down some basics about the book:

Title: ________________________________________________

Year of publication: ________________________

Author: ______________________________________________

- List a couple of things you can tell about the author from the book jacket or the “about the author” section at the front or back of the book.

- Is there an introduction by the author or someone else?

Skim at least a few pages of the introduction (or the first chapter, if that’s more helpful). Then write down a key sentence or 2 that tells what the book is about.

- Take a look at the book’s index. (If there’s no index, skip to #5 and find two stories rather than just one.)

Helpful index-skimming tips:

- An italicized page includes one or more pictures.

- Hyphenated pages (e.g., 155-167) indicate a section that probably holds a lot of material on one particular topic.

Turn to one of the sections from the index that looks interesting, and write down a fact or quotation you like (with page number in parentheses).

- Find an interesting story.

- In the Table of Contents, look for a chapter that seems to have an interesting topic, and flip to that chapter. Then, look for a story that seems intriguing about someone or something. It won’t always be at the beginning of the chapter. From there, read a little bit more before or after the story (a page or two) to get context.

- If this doesn’t work, try looking in the Table of Contents again.

- Usually by the second or third try, you will find a story that lights you up and leads somewhere new.

Describe in a couple of sentences what the interesting story is about (include page #s):

- Wrap it up and reflect!

Answer any or all of these questions in a couple of sentences total. Feel free to write on the back.

- What topic of research paper would this book be most useful for? Be specific.

- How could you use this book if you were writing a paper about a reformer?

- Did this book end up being what you expected, or was it something different from what you expected?

Download a PDF of the handout.

Stories Spilling Out

The most fruitful element of the handout was #5, which asked students to find a story, and to try again if they didn’t hit pay dirt immediately. In the drafts that students turned in a few weeks later, suddenly I was reading anecdotes that made their papers about reformers catch fire on the page.

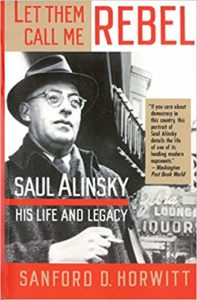

For instance, Sage pulled in a quotation from community organizer Saul Alinsky about a race riot in 1964 in Rochester, New York, where the Kodak company was based. Alinsky asserted, “Kodak’s only contribution to race relations was the invention of color film” (from Sanford Horwitt’s Let Them Call Me Rebel: Saul Alinsky, His Life and Legacy, Vintage, 1992). Quotations like this literally added color to her writing.

For instance, Sage pulled in a quotation from community organizer Saul Alinsky about a race riot in 1964 in Rochester, New York, where the Kodak company was based. Alinsky asserted, “Kodak’s only contribution to race relations was the invention of color film” (from Sanford Horwitt’s Let Them Call Me Rebel: Saul Alinsky, His Life and Legacy, Vintage, 1992). Quotations like this literally added color to her writing.

Overall, the students may not have found the absolute best story in every book, but they found ones that were more than good enough.

Showing Them How

In reading students’ drafts and nodding my head at the aptness of many of their quotations, I realized that I had made visible one of the research-reading strategies I take for granted, one I had learned over many years of trial and error.

In an anonymous survey I gave a month later asking how their historical writing had improved so far this year and what they would still like to work on, I was surprised that a significant number of kids commented on how much they had appreciated the “How to Read a Book” assignment, with observations such as “The activity where we learned how to read a book helped a lot with finding information and citing sources” and “I think the learning how to read a book activity really helped me find information faster.”

This is definitely an exercise I’ll do again each year. Beyond its improving students’ skills, it brought me joy. Seeing an entire class full of kids dedicate themselves to a nonfiction book for an entire period was a moment I’d like to repeat!

________________________________________________

For ideas on folding current events and civics into your classes throughout the school year, try Sarah Cooper’s book, Creating Citizens: Teaching Civics and Current Events in the History Classroom, Grades 6–9, a Routledge/MiddleWeb publication. MiddleWeb readers receive a 20% discount from Routledge with the code MWEB1.

For ideas on folding current events and civics into your classes throughout the school year, try Sarah Cooper’s book, Creating Citizens: Teaching Civics and Current Events in the History Classroom, Grades 6–9, a Routledge/MiddleWeb publication. MiddleWeb readers receive a 20% discount from Routledge with the code MWEB1.