Nurturing Truth-Seeking Communities in School

By Pablo Wolfe, Mary Ehrenworth and Marc Todd

Pablo

As educators, the pursuit of Truth is central to all that we do.

Truth-seeking is the process of inquiry, fact-finding, and evaluation that we facilitate in our classrooms every day. We look at multiple sources and perspectives, weigh their credibility, and form a consensus about what we as a community know.

We resist simple answers, question orthodoxies, and face discomfort together. Truth-seeking is the constant communal effort required of our classrooms, and our society, that makes justice possible.

Mary

Unfortunately, over the course of our nation’s history Truth has been recorded from a singularly white perspective, and in ignoring the realities of Indigenous, Black, and immigrant peoples, our nation has constructed a deluded vision of itself.

As Ibram X. Kendi has recently said, “Denial is the heartbeat of America.” While this has been the case throughout our history, we now have technological tools that further segregate us into ideological bubbles and magnify blind passions and beliefs at the expense of Truth-seeking.

In recent memory we have seen what happens when truth is conflated with belief: we get climate change deniers, folks unwilling to wear masks during a pandemic, and armed rioters invading the Capitol.

Marc

In the face of people rejecting a democratic process, it is more vital than ever that our classrooms prepare young people to be Truth-seekers and to reject anti Truth-seeking currents within our society.

It was towards this end that we wrote The Civically Engaged Classroom: Reading, Writing, and Speaking for Change. We wanted to offer suggestions on how to create Truth-seeking communities in our schools and how to inoculate our students against the viral spread of falsehood in the American bloodstream.

It is also the reason that Pablo has created The Coalition of Civically Engaged Educators (CCEE), a network of civic education practitioners who seek Truth in their practice through collaboration with peers.

In our work we explored many ways to foster Truth-seeking communities. Here, we want to offer three foundational inquiries to support the Truth-seeking in your own classroom.

What biases do we bring to our Truth-seeking community and how can we excavate these?

Without realizing it, our own biases can become the biggest impediments to creating a Truth-seeking community.

We can start the process of anti-bias work by exploring our own identities, including our age, gender, race, ethnicity, culture, and sexual orientation. Whether through autobiographies, identity webs, mapping, journaling, poetry or some other means of self-expression, we can consider who we are as we enter the classroom. In light of these identities, we can then ask ourselves:

► How have these aspects of my identity shaped my experiences in the classroom?

► How have these aspects of my identity shaped my perceptions and assumptions about my students?

► What are my fears about my students? Where do those fears come from?

► Who is more visible to me? Who might I tend to be more sympathetic to, or less sympathetic to? Why?

► Which aspects of my identity am I reluctant to share with my students? Why?

► Which aspects of my identity will my students be most interested and engaged by? Why?

► How will I check in with myself about my assumptions and how they are affecting my teaching and relationships?

While this work can be done quietly, in self-reflection, wading through discomfort with others helps us grow. We can look for colleagues with whom we can feel vulnerable and who can call us on our blind spots.

As institutions, schools have their own assumptions about students and their own ingrained biases as well. An honest thought-partner in this work can help us examine both those biases that are part of us and those that are part of the school community.

We can also ask the administrators of our schools to build in opportunities for colleagues to think and grow together, so we can better see, and serve, all our students.

How can I create opportunities for students to explore their biases?

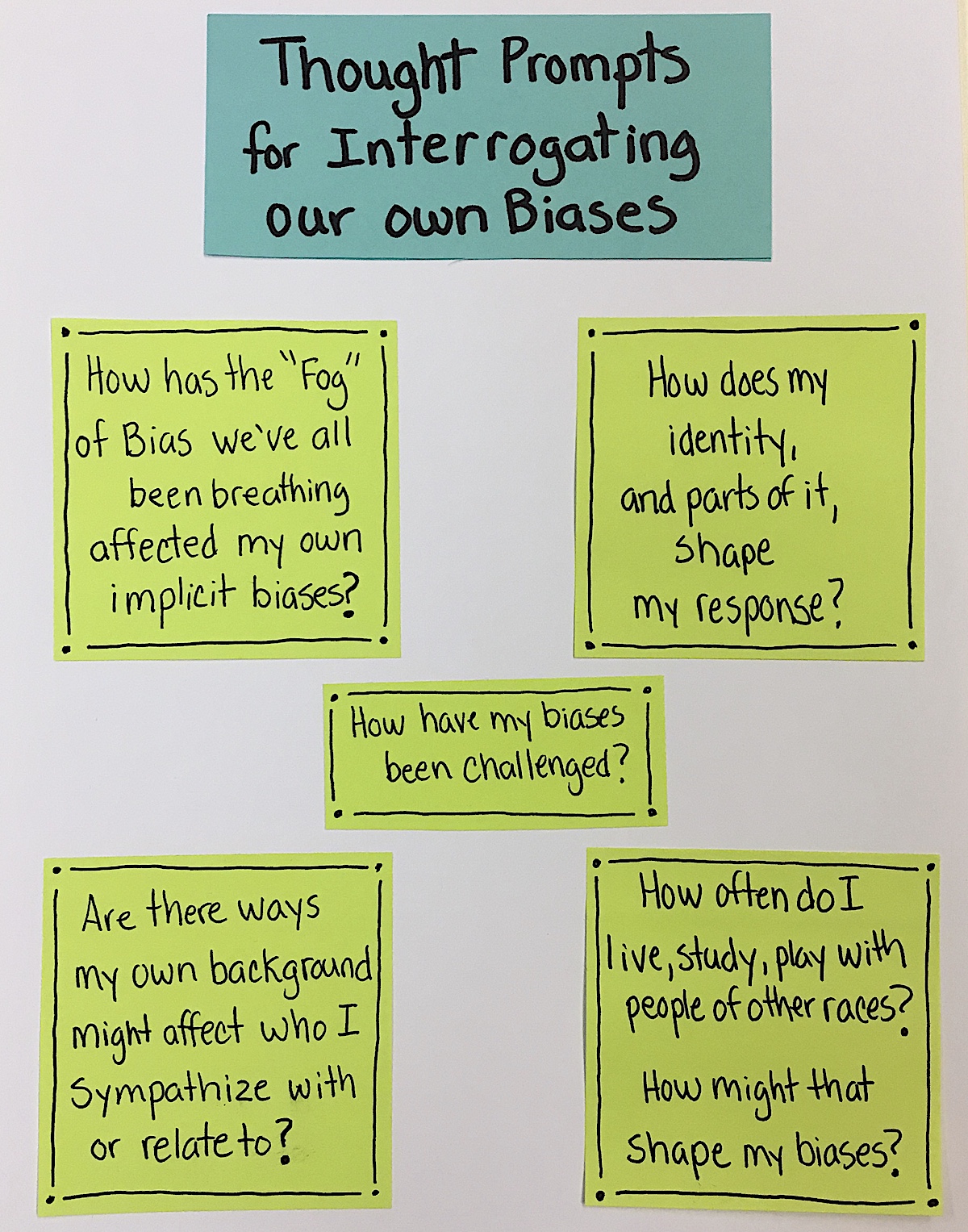

Students will enter our classrooms with their own biases. We can support students in identifying bias by providing them with tools and time for introspection. Below we offer some thought prompts to help students reflect on their implicit biases. These prompts are designed for students to explore their ideas in writing before joining a small group, or affinity group, or class conversation.

The chart below can be used before beginning study of a controversial topic or issue. Students can explore where their own dispositions are leading them at the outset of their study, and then they can revisit these assumptions at the end to see how they’ve been changed, or challenged.

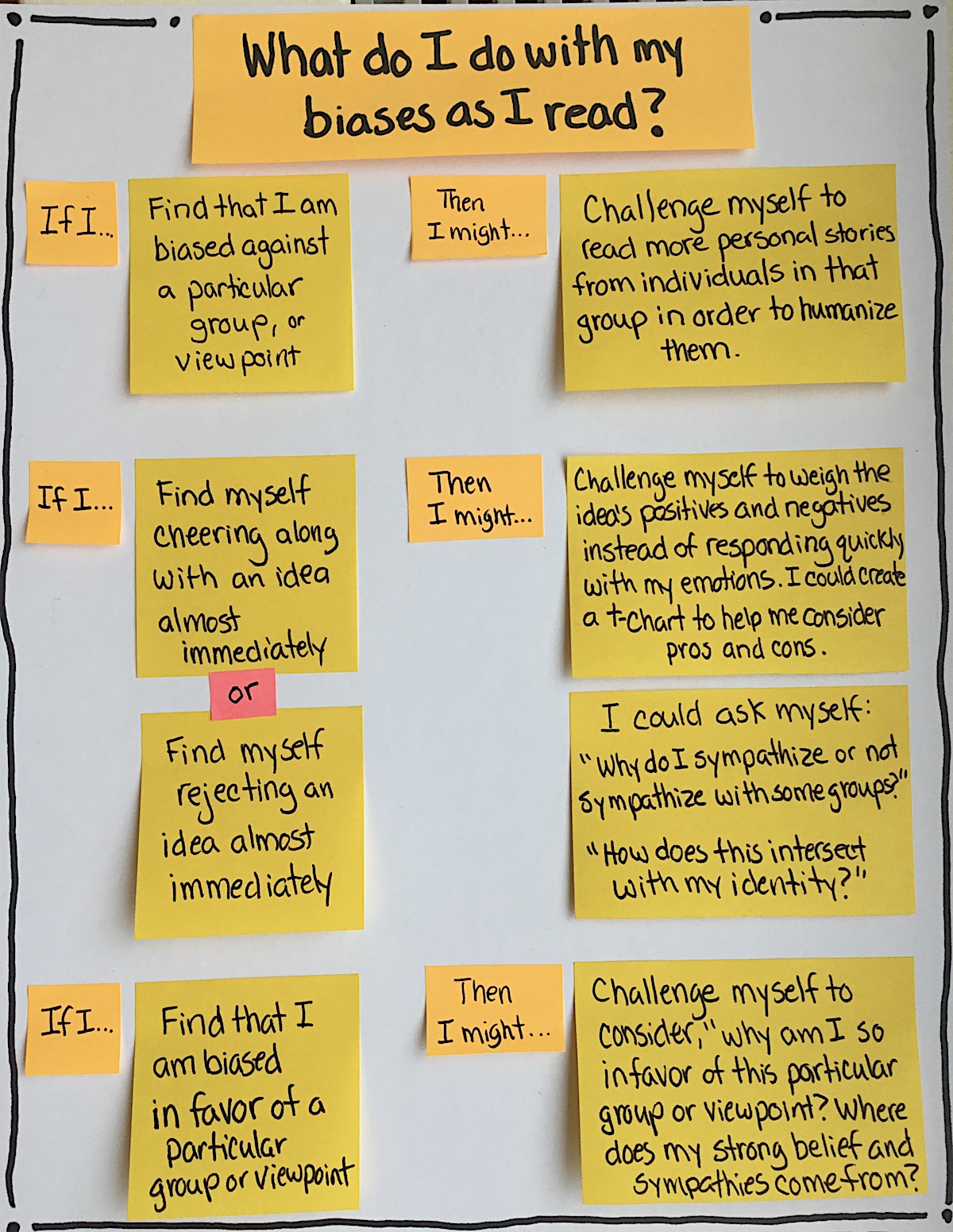

Identifying their biases is only one step. We’ll also want to equip our students with strategies for dealing with those biases. An If…Then… chart might provide useful strategies as students become more self-aware.

We cannot count on this work taking hold in a single activity. It must be repeated and re-examined throughout our students’ time with us, and then reinforced by our colleagues. We must consider how we will vertically align these skills so that students have an opportunity to revisit them as both their self-awareness and the complexity of their texts increase.

These efforts are best undertaken as a whole building. Again, it’s in community that we will most effectively seek Truth.

What kinds of social action projects might students engage in?

Often our Truth-seeking in our text-dominated society is limited to that which we read on the printed page, but we have the opportunity to change this paradigm and to create school experiences that offer alternative ways to seek Truth as a community. In our experience as educators and in our research for the Civically Engaged Classroom, we found extraordinary examples of Truth-seeking through social action projects.

One of these was organized by Akeem Barnes and Aaron Hinton, who invited their students to examine the aspects of their community they would like to change. Together, the students chose to address police-community relationships. Their intensive research centered the voices of experts in their community.

Akeem’s students went home and talked to parents, siblings, cousins, uncles, aunts and neighbors. They stood on the street corner and interviewed passers-by. Chaperoned by elders from the community, students went to the local library, a civic hub which houses the Brownsville Historical Society. Their research there was led by the local librarian and an elder with a lifetime of experience in the neighborhood. Expertise came from the community and Truth-seeking was its shared mission.

Akeem’s students surveyed over 200 community members and discovered that ⅔ of them did not know that there was a Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB), a body designed to redress citizen grievances against the police. This discovery, presented at a community town hall meeting hosted by the school and attended by representatives of the 73rd Precinct, led to the precinct increasing their advertising and outreach efforts.

Communal Truth-seeking can take any number of forms. We’ve talked to teachers whose students have made maps of COVID vaccination sites, authored voting guides for local and national elections, designed pamphlets for local environmental efforts, lobbied for school water testing, and painted murals for victims of racial violence.

The types of projects students and teachers have taken on is wide and inspiring. We share a number of them in the “Educator Spotlight” and “Young Citizens in Action” sections of our book.

The only requirements for these social action projects are that they:

► Originate from young people and their concerns

► Take stock of the countless assets and expertise residing in the community surrounding the school

► Require research or inquiry about the issue and the people engaged in addressing it

► Involve direct action

► Offer chances for regular reflection

How do we find courage for this work?

All of this will take deep reservoirs of courage. It is natural that as educational leaders we fear accusations that we are politicizing the classroom, but let’s examine that fear. Have classrooms ever been apolitical? As long as classrooms are a space in which ideas are exchanged between human beings, they are, and always have been, political spaces.

Let us draw the distinction: the pursuit of Truth through inquiry and debate may be political, but it does not need to be partisan. Remember that we are not telling kids who to vote for, or what is true. We are teaching them to seek knowledge, perspectives, and histories from many sources, and to work with that knowledge to increase justice.

That said, we must draw a line. As leaders of Truth-seeking communities, we are under no obligation to give equal airtime to racism, hate speech, lies, and conspiracy theories in the name of “fairness.” To the extent that any political organization aligns themselves with these, they are writing and speaking themselves out of our Truth-seeking community and our curriculum.

To find strength in these times we again suggest turning to community. Veteran teacher Rachel Hsieh has suggestions for how to treat parents as vital participants in our classroom Truth-seeking rather than as potential impediments. She offers her thoughts on handling politically sensitive issues with parents in both our book and in a blog post available at CCEE.

The challenges facing us as we move forward as a society are daunting, and they require us to take stock of ourselves, our curricula, and everything that we have taken for granted in our education system.

Ultimately, we must begin by directing our Truth-seeking gaze at ourselves. As Dr. Sonja Cherry-Paul said in her article, If You Think Racism is Too Political for Your Classroom, Think About What Your Silence Says, “We can’t change what we won’t confront.”

See our MiddleWeb review here.

Pablo Wolfe is a Washington DC-based educator who promotes civic education as a means to improve student engagement, celebrate student identity, and embolden the next generation of activists. He’s been a public school administrator, a staff developer with the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project, a teacher, and a parent, and in all of these roles has sought to make school a training ground for civic life. Pablo believes academic skills are best learned when applied towards addressing social injustices. A strong believer in the role of teachers as agents of social change, he strives to thread this idea through his writing, staff development and teaching.

He is the founder of the Coalition of Civically Engaged Educators. Visit https://www.civically-engaged.org to learn more. You can connect with him on X-Twitter @pablowolfe.

Mary Ehrenworth is , Mary’s interest in critical literacies, deep interpretation, and reading and writing for social justice all inform the books and articles she has authored or co-authored.

Marc Todd teaches Social Studies at IS 289, the Hudson River Middle School in New York, and is a national presenter for the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project. He collaborates with teachers around the world and leads workshops and institutes on culturally relevant pedagogy and teaching students to be critical readers of history. Marc believes in immersing kids in nonfiction reading and making notebook work inside of content classes both serious and joyful. He incorporates Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed and Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed into his curriculum. You can connect with him on X-Twitter @marctoddnyc.