Cris Tovani: Use These 6Ts to Deepen Learning

Nervously, I stare at my computer screen, hoping that students on the other end will click the sticky note icon and add thinking to the Jamboard. To my relief, a few begin posting.

I read each one looking for patterns of confusion and understanding. But wait! What is that red, rogue pen doing making wild squiggly marks all over the screen? At the head of the squiggly line is a circle too small to see and no doubt frames the face of the culprit maneuvering the menacing red line around the stickies that more compliant students have added.

This is my first virtual Literacy Lab. Hired to model engagement strategies online with a seventh-grade geography class, I have to remember to focus on what matters most.

To Engage, We Have to CYA

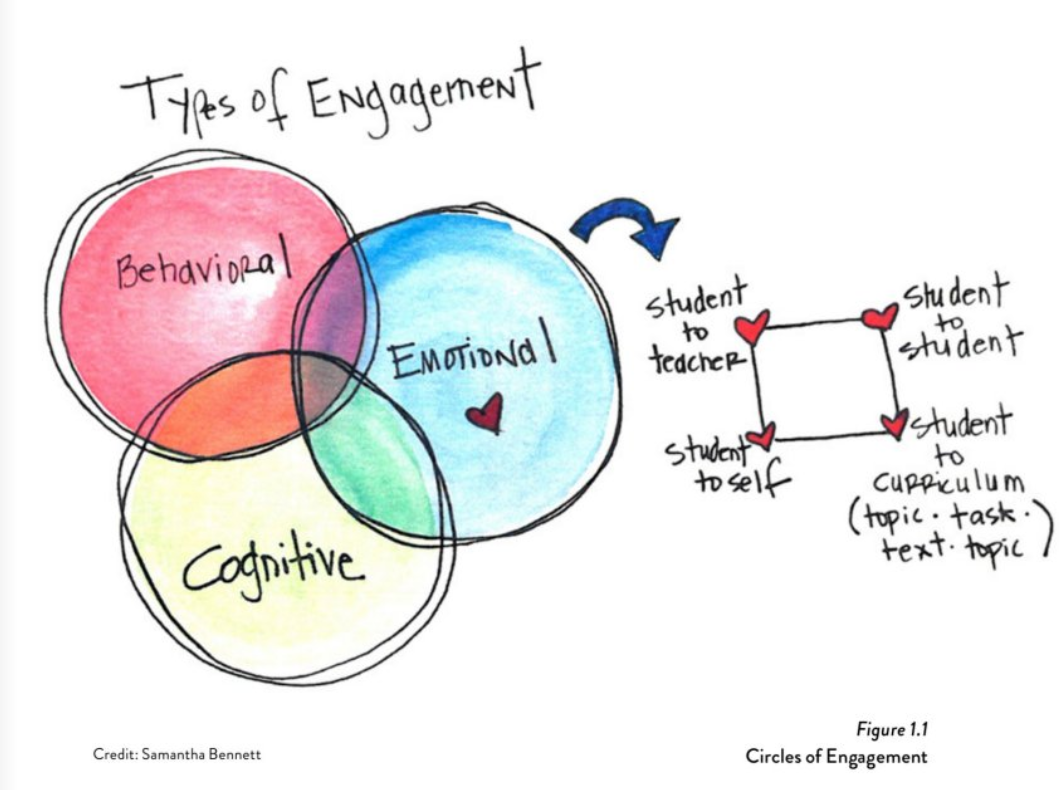

Deeper learning can happen remotely, but in order for it to occur I have to CYA. I do it by using what I call Curriculum You Anticipate structures. These structures correspond with the 6Ts for literacy learning I’ve developed (Tovani, 2021) from the 4Ts described by Ron Berger and his colleagues in Transformational Literacy (Berger, et al., 2014).

The 6Ts are: Topic, Target, Task, Text, Time, and Tending.

After the first day of the 7th grade demo, I go through my list of 6Ts, using it as a checklist to posit what students might need tomorrow to engage. Why didn’t some kids read? Do they need a different text or way into the topic? Maybe the ones who didn’t participate need a little tending because they don’t yet trust that I care about what they have to say?

Was the learning target clear, and did I give them enough time to understand and own the purpose for reading? Maybe they need to see that the task is worthy of their time, so I’ll share the responses of the few kids who wrote the previous day so they can see a model of what I want?

These are all daily shifts I can make, but I’ve learned over the years that even the best daily strategies won’t work if students aren’t engaged over time with a big idea that matters. So when I’m invited to do a demonstration lesson in another teacher’s classroom, I don’t just model some random literacy strategy. There has to be context and purpose.

Even though I might only demo in a classroom for one, two, or three days, I create a long-term unit plan like I would for my own students. If I don’t believe that the work I ask students to do will make them more knowledgeable, skilled, and interested humans, why should they engage?

Cradling the Standards in a Compelling Topic

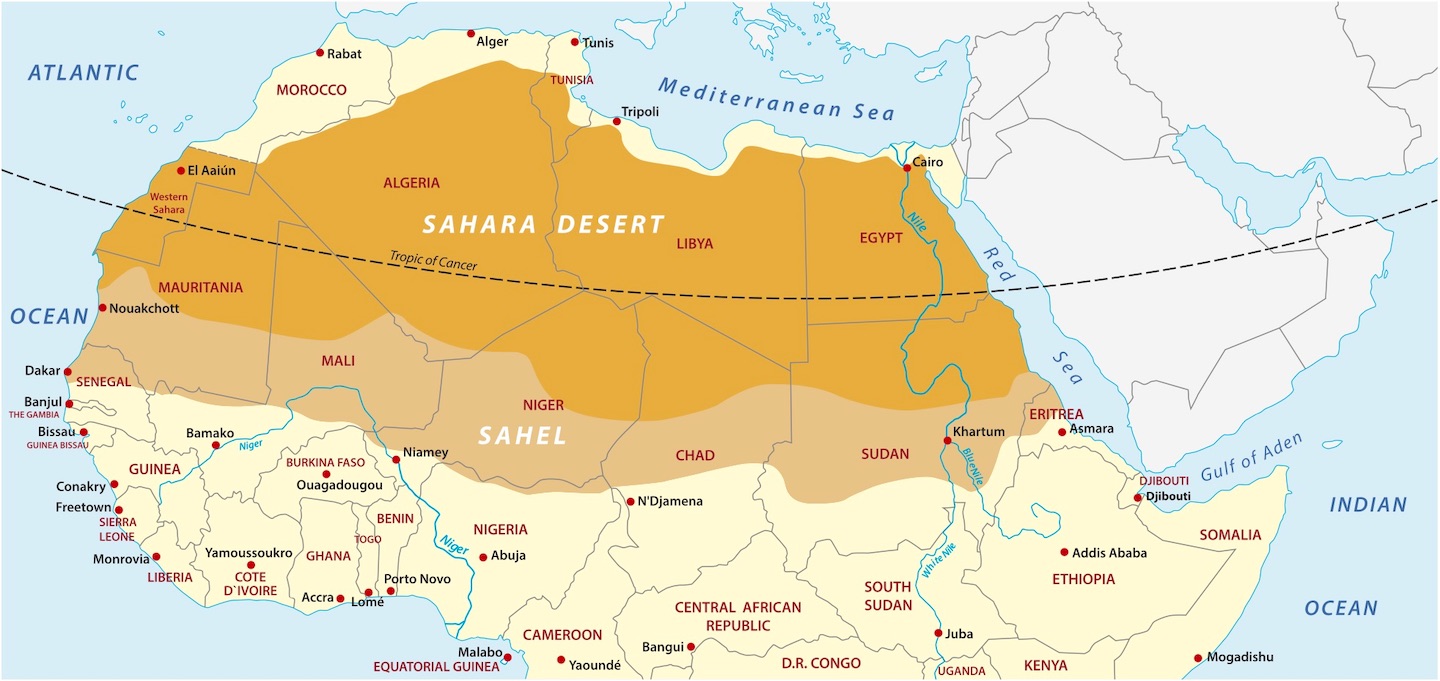

I’m working with the 7th grade class on its third day of studying Africa. So far, the teacher has taught about the Sahara Desert and the African Sahel. I’m told that I can teach about oases on the first day of my visit.

With only two fifty-minute class periods, how much could students know about the Sahara and the Sahel? Not being a social studies teacher, I don’t know why learning this content matters and I know the seventh graders are probably are thinking the same thing.

I email the teacher and ask, “Why does knowing about the Sahara Desert, the African Sahel, and oases matter? Of all the things you could teach kids right now, why study this? Other than they might be in your standards, how does knowing a few geographical features of Africa prepare students for the world outside of school?”

Click to enlarge

Several hours later, I get a response in the form of a question, “Did you know that the Sahara is growing at an alarming rate?”

I email back, “So, why should seventh graders thousands of miles away care about that?”

Immediately, he responds: “All over the continent, drought and weather extremes are displacing millions of people, making them climate refugees. Fighting over land and water is causing violent uprisings and is destabilizing local control. We’ve learned from Covid that catastrophic events go beyond locales and affect people all over the world.”

I email back, “Now, that’s compelling! Thinking about how climate change effects people and animals makes me care about learning the information.” We brainstorm a few provocative questions designed to give students more reasons to read, write, and discuss:

- What can a seventh grader do to help climate refugees?

- What should people know about Africa?

- Is climate change really affecting how and where people live?

- What happens to people and animals when there is a drought or flood?

I’m starting to get excited about digging in with the students and hearing their thoughts…

Targets Connect and Scaffold

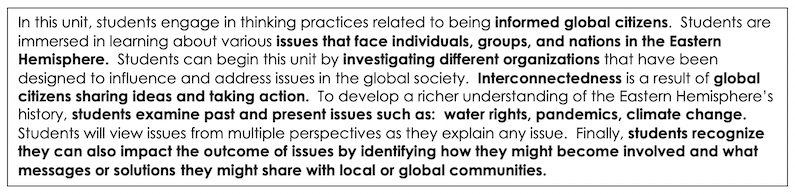

After figuring out why a topic is compelling, we head to the standards to help us sift, sort, and prioritize key learnings. Below is the district’s overview of what students should know and be able to do after the unit. Emboldened in black are the words that guide our planning (click to enlarge).

To hit the standards, the teacher and I need to design a few learning targets in student friendly language that will inspire, guide and scaffold learning. First, we write a few long-term unit targets. It will take several weeks of reading, writing, and discussing before students are able to reach them.

Unit Learning Targets:

- I can describe what it means to be a global citizen.

- I can describe the circumstances and conditions that force people from their homes.

- I can explain why the world needs geographers.

After fleshing out the unit learning targets, we write a few supporting targets that represent key lessons to scaffold and support students’ reading, writing, and researching as they develop the behaviors and habits of citizen-geographers in the world.

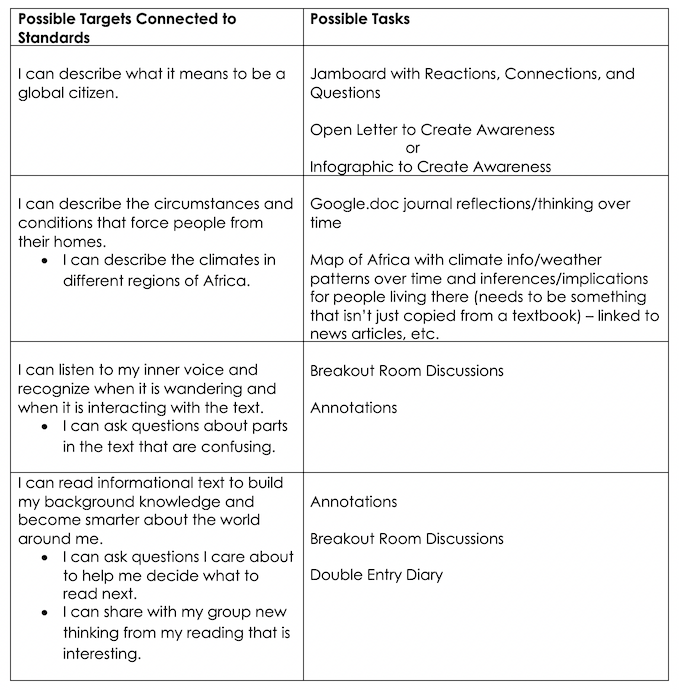

Tasks Give Students a Way to Demonstrate Understanding

If I want students to hit the targets, I have to give them a way to show me what they know and need. Below is the chart the teacher and I brainstormed of possible targets and long-term and daily tasks for the unit.

Identifying what I want students to know and be able to do over time helps me decide on a daily basis what students will read, write, and talk about. If I plan ahead and have a compelling topic with targets and tasks planned out, I can use the other 6Ts to make little adjustments day to day.

Time to Read, Write, and Discuss

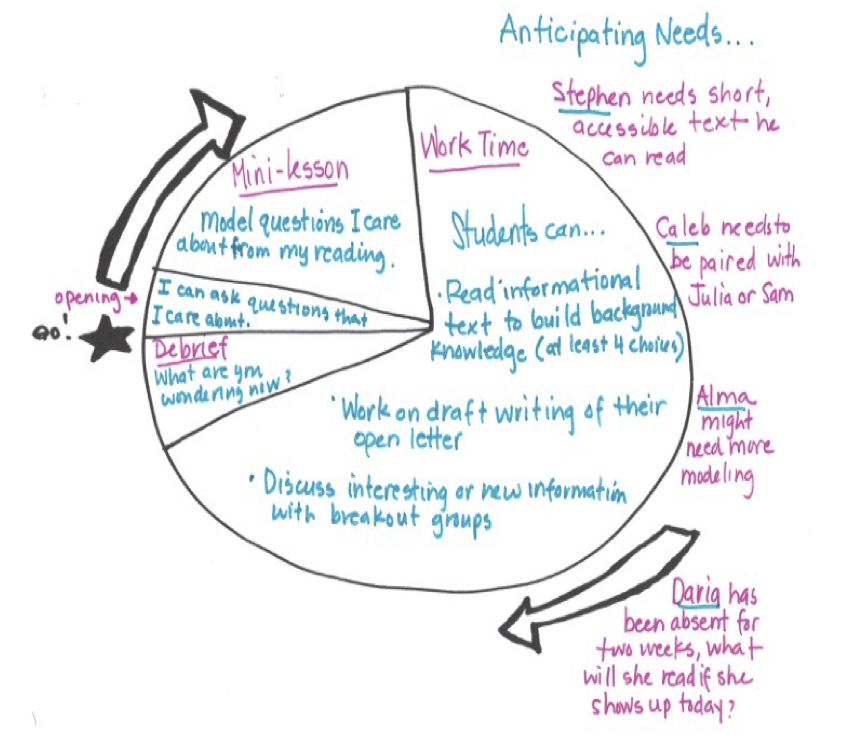

If students are going to grow as readers and writers, they need lots of time to read and write. That means I have to plan for them to work for more minutes than I talk. Using my instructional coach Samantha Bennett’s model for planning a daily workshop (Tovani, 2021, Bennett, 2007), I start my daily planning with student work time, then work backwards to think about what they’ll need from me to work with more agency and ownership than they would if I just gave them the assignment.

The workshop planning wheel helps me figure out how to integrate my targets and tasks when I am with students. When I plan ahead what kids will do and anticipate some of the stumbling blocks, I free myself up to listen in on conversations, confer with students in break-out rooms, and actually do a bit of differentiation.

Mr. Red Rogue Pen Takes Off His Mask of Disengagement

The second day of the demonstration lesson goes better. I start the class by thanking students who left their thinking on the Jamboard and Google Doc. I invite them to read the comments I wrote in response. I throw out a call to others who didn’t respond, letting them know that we need their thinking as well.

At the end of the day, Mr. Red Rogue Pen has identified himself as Kenny. Instead of scribbling all over the page, he writes comments on the Google.doc. inferring that, “Maybe people fight each other because they need farmland.”

Sabina, another student who wrote nothing the first day, asks, “Why don’t people just go to the rainforest to get materials so they can fix their house?”

Some kids return to the provocative questions from the day before. They add more thinking. Reid uses his background knowledge to help him infer. He writes, “Don’t you remember last summer’s wildfires that were so bad? People had to leave their houses really fast or they would have burned to death. Maybe that’s why people in Africa have to leave their homes.”

By the third day students have had a taste of African regions and have started labeling some of the consequences droughts and flooding have on people and animals. They are fired up that something needs to be done.

Tawny writes, “We can help increase people’s awareness of what is happening. We can talk to people and see if they can donate or help in any way.”

Mia adds, “A seventh grader can do a lot if they put their minds to it. They can help send supplies to people and donate food and money.”

I kill the buzz when I write two questions in the chat box, “What will you put on your infographic or write in your open letter to create awareness? Where do we send supplies and money so the people who need it, get it?”

Most kids don’t respond. It’s a signal they need more information and models of others who have taken up the call to action.

Daniel calls my bluff, no doubt an expert at playing the game of school. He writes, “There are three different supply ports spread out over the desert. Villages can send a camel caravan to the port closest to the area of impact and pick-up supplies.” I smile knowing he might be doing a little research and little line lifting. But that’s ok, the next step for him is to model how to quote the thinking of others.

It’s only been three days and students’ curiosity has been sparked. They are ripe to read, write, and figure out what they can do as global citizens. When we plan to engage students using the 6Ts, deeper learning can happen—even online. Trusting kids to think, giving them something compelling to think about, and providing opportunities to read, write, and share with others helps to remove the masks of disengagement.

from Why Do I Have to Read This? Cris Tovani (Stenhouse 2021)

from Why Do I Have to Read This? Cris Tovani (Stenhouse 2021)

References

Bennett, S. (2007). That workshop book: Systems and structures for classrooms that read, write, and talk. Heinemann.

Berger, R., Woodfin, L., Plaut, S.N., Dobbertin, C.B. (2014) Transformational literacy: Making the common core shift with work that matters. Jossey-Bass.

Tovani, C. (2021). Why do I have to read this: Literacy strategies to engage our most reluctant students. Stenhouse.

Read the first 2 chapters here.

Cris Tovani is an internationally known consultant who focuses on issues of disciplinary reading and writing instruction. She was awarded the 2017 Thought Leader Award from the International Literacy Association. Cris has been an adjunct professor at the University of Colorado and the University of Denver.

She is the author of five books, including the best-selling classic I Read It, but I Don’t Get It, and most recently, Why Do I Have to Read This? Literacy Strategies to Engage Our Most Reluctant Students. (Stenhouse, 2021)

Cris has taught students from grades 1-12 and continues to study the “knowing-doing gap” by investigating how best practice research can be practically applied to a variety of instructional settings.