Teach Kids to ‘Read’ the Images They See

Every day, images pass across our screens. They exist everywhere: on television, webpages, social media, newspapers, magazines, textbooks, mobile phones and more.

Every day, images pass across our screens. They exist everywhere: on television, webpages, social media, newspapers, magazines, textbooks, mobile phones and more.

Photographic images get attention in the 21st century. They get respect. They can teach.

In Social Studies, for example, they are considered “primary sources.” In English Language Arts, they are the “non-print informational texts” that teachers use. And in the Visual Arts, they are art forms – media that students will analyze for technique and creative value.

Photos are so ubiquitous, we often don’t give them much thought. Who took that picture? (authorship); why did they take it? (purpose); where is it seen? (media, exposure); what message might it convey? (interpretation); has it been altered and if so, why? (creative expression, manipulation).

These are the kinds of “media literacy” questions that students should be taught to consider as they encounter photos in the news, in marketing situations, in social media.

How to Read A Photograph

Despite some nods toward “visual media as text” in education standards, teaching students to approach photographs with a critical eye does not appear to be commonplace in American education. But it should be. “A picture is worth a thousand words” is a common expression many of us have heard. But how many of us have invited students to really think about what that means and why people say it? Can we find pictures WE think are worth a thousand words. That would make an interesting media literacy activity.

Learning to read photos is not always a simple process, but when done properly, it can be rewarding to both the teacher and the learner. Try this warm-up activity: Download this PDF and have students follow the “Read a Photograph” tips as they study the image below without any context clues. (Do any guess the scene is not taking place in the USA?) The same tips can be applied to more complex imagery.

Youth soccer game in Serbia

Visual literacy often gets covered at the elementary level, but it’s been my experience that analyzing and interpreting images does not always receive the same attention at the middle school level. How can we change that? By exposing students to images and helping them learn to “read” and deconstruct them.

What’s Happening Here?

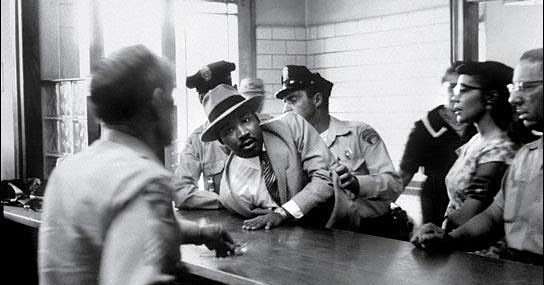

Once your students have the basics of “reading a photo” in mind, you might try something more challenging. Here is a photo I’ve used in some of my recent workshops and webinars. I leave off the caption so there is no context. Students may recognize the subject at the center of the image, but that is not the objective. Because so few of our students have had any real photographic or visual literacy training, they may not know HOW to examine or “interrogate” an image of any complexity. (This image is not under copyright.)

A good way to start with students is to ask the simple question: What do you see? (They can create a list.) Because the caption has been omitted, they must examine it closely and make inferences based on their observation. Here are some questions you might use to guide their research and analysis:

- Who took the picture? Since there is no caption, students must use their research skills to find the answer to this one – I previously wrote about photojournalist Charles Moore here.

- What is the setting? What are the clues?

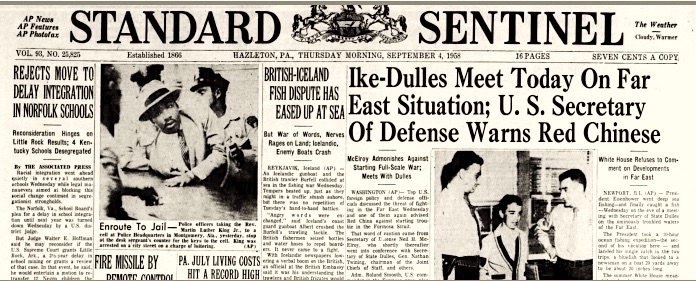

- Where was it seen/published? When? Students researching this image will find it duplicated many times on the internet; but what about newspapers or magazines of the time? Wikipedia indicates it was taken for the Montgomery Advertiser and distributed by the Associated Press. Using a subscription database, I found this newspaper used a cropped image on its front page on the day following the event (click to enlarge).

- What was the photographer trying to capture? Why?

- Notice the people’s faces. What might their expressions communicate?

- Is there a story behind the image? (There is.)

- What were the circumstances around this arrest? What might it reveal?

The original caption for the photo, written by the photographer, read: “Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is arrested for loitering outside a courtroom where his friend and associate Ralph Abernathy is appearing for a trial in Montgomery, Alabama.” 1958.

Photo Manipulation’s Long History

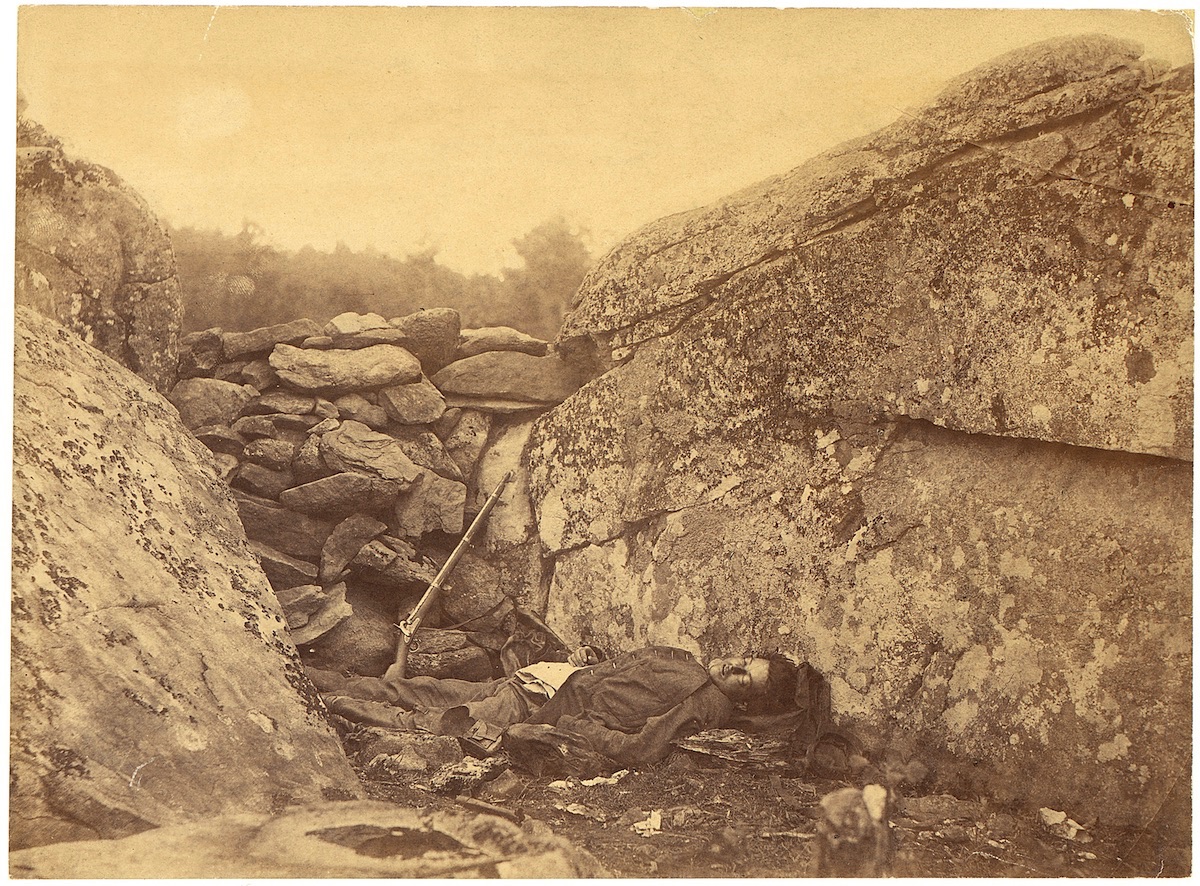

I use at least one historical image in all of my media literacy workshops to get teachers and students to conduct what I call a “close read.” This one fascinated me, especially when I learned the backstory that made the photograph and the photographer famous.

This photo has a title, “Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter,” and it is attributed to Civil War photographer Alexander Gardner. Right away, in this case, I have revealed more details about the image than the previous one. If you use this in an activity, you can decide how much your students need to know at the start.

Source: MOMA Learning

Source: MOMA Learning

Students may not question this picture of an apparently dead soldier with his gun leaning against the wall, inside what we would call today a sniper’s nest. But they might be surprised to learn that this photograph taken at the Battle of Gettysburg was “staged.”

According to the Museum of Modern Art, “analysis revealed that he (Gardner) had staged the image to intensify its emotional effect. Though this practice was not uncommon at the time, its discovery made the photograph the subject of controversy. Gardner moved the soldier’s corpse and propped up his head so that it faced the camera. He then placed his own rifle next to the body, emphasizing the soldier’s horizontality and the cause of his death.” (Source)

The truth is that ever since photographs began to be published and widely distributed in the 1880s, images have been manipulated to fool the public. For example, middle schoolers might be intrigued by the story of the Cottingley Fairies, five photos of ethereal creatures allegedly taken by an adolescent girl in 1917 that managed to fool Sherlock Holmes creator Arthur Conan Doyle.

The truth is that ever since photographs began to be published and widely distributed in the 1880s, images have been manipulated to fool the public. For example, middle schoolers might be intrigued by the story of the Cottingley Fairies, five photos of ethereal creatures allegedly taken by an adolescent girl in 1917 that managed to fool Sherlock Holmes creator Arthur Conan Doyle.

The modern manipulation of images is the subject of a webpage I created entitled “Is Seeing Believing?” A lengthy list of other useful resources can be found there, including The Bronx Documentary Center of Altered Images.

Photo Fakery Is Now Common Practice

In a much-quoted 2016 Stanford study, middle schoolers failed to question or verify a photo of what appeared to be “deformed daisies” on a photo-sharing webpage which claimed the flowers were proof of genetic damage caused by the accident at a Japanese nuclear power plant – even though no source was given.

Photo altering and misrepresentation have become a common practice in today’s media landscape, and learning to question the authenticity of sensational images is more important than ever.

In 2018 The New York Times asked readers to contribute examples of election misinformation. Readers came through with more than 4000 examples, and many involved photos. Here is one they received aimed at discrediting Georgia political leader Stacy Abrams, who was then running for governor:

Both National Geographic Kids and Scholastic News have previously addressed the issue of altered images in their publications, and having your students check out these books, videos and articles might also be helpful.

Verify the Image Activity

Many students post and repost photos they’ve seen online without bothering to validate or verify authenticity. With that in mind, I created the VERIFY THE IMAGE activity – a web page of images that you can use to challenge your students’ critical thinking and viewing skills. You simply assign an image to a student (or group of students). It’s their job to document the steps they took to verify whether an image is real or not.

Several images from Frank Baker’s “Verify the Image” activity

Several images from Frank Baker’s “Verify the Image” activity

Now that your students have taken time to analyze images, they may feel better prepared to interpret the plethora of images that they might be exposed to on their social media/news feeds.

Activity Suggestion: Ask students to bring in a news photo (printed if possible) that they saw on Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat or any other social media they attend to. They should be prepared to present an “image analysis” to the class based on their research and investigation.

Images on Magazine Covers

In my blog posts I’ve previously written about how to engage your students, for example, with the images that adorn magazine covers. In 2020 I co-hosted two webinars that centered around these covers: one looked at covers that represented the Pandemic and the other examined the way President Trump was represented during his four-year term. Watching either one of these will be helpful as you learn how to engage students in both visual and media literacy. [See my magazine database of Trump covers.]

In my blog posts I’ve previously written about how to engage your students, for example, with the images that adorn magazine covers. In 2020 I co-hosted two webinars that centered around these covers: one looked at covers that represented the Pandemic and the other examined the way President Trump was represented during his four-year term. Watching either one of these will be helpful as you learn how to engage students in both visual and media literacy. [See my magazine database of Trump covers.]

As educators, you have access to magazines at home and at school (e.g. the school library). I maintain these magazine covers are texts you can use to teach visual literacy, symbolism and more.

So much of our world is visual. Helping students learn how to “read” images should be part of a 21st century education. I’d enjoy hearing how you engage students in “visual literacy.”

Recommended Resources:

► Reading The Pictures (website/weekly analysis of current event images)

► Reading The Pictures (archive of February 2021 webinar)

► Civic Online Reasoning: Evaluating Photos Lesson Plan (Stanford – registration required)

► Evaluating Photos & Videos (excellent Crash Course video with John Green)

► Visual Literacy: Definition & Examples | Study.com

► Photo Fact-Checking In The Digital Age (tutorial, The News Literacy Project)

► What’s Going On In This Picture? (weekly New York Times Learning Network activity)

► Common Core in Action: 10 Visual Literacy Strategies (Edutopia)

► Visual Literacy for Libraries (book)

► Close Reading of Photos and Graphics (worksheet, Scholastic/UPFRONT)

► Library of Congress Photograph Analysis (worksheet)

Frank W Baker is a longtime contributor to MiddleWeb. His book “Close Reading The Media” includes more ideas and resources in visual literacy and photography. He maintains the internationally recognized Media Literacy Clearinghouse website of education resources. Baker has conducted hundreds of workshops with educators over the past 20 years. You can reach him at fbaker1346@gmail.com and on Twitter @fbaker.