Let Your Students Figure Out Their Misconceptions

As you self-reflect after a long teaching day, unit, or extended break, Kelly Owens’ series of UN-to-RE articles will deepen your thinking about what needs UNDOING and present ways to RESET for greater student success. Her third article highlights teaching practices to help students UNLEARN mistaken ideas through self-REPAIR strategies.

Have you ever tried to correct a misunderstood concept to the point you’re absolutely bone weary? And your middle graders still dig in their heels and won’t budge?

It’s tempting, I know, but whether the confusion involves a faulty math algorithm, a mistaken science phenomenon, or a fragmented literary concept, serving up the correct answer on a silver platter isn’t the best solution.

Misconceptions occur when we don’t understand a concept completely or accurately. They are normal parts of the learning process. We begin learning during childhood as we explore and observe the world around us. It should be no surprise we need to continue refining some concepts. Let’s look at ways to help students fill their knowledge gaps through their own effort.

Getting to the Aha Moment

Middle school students (and adolescents generally) are famous for thinking they know E-V-E-R-Y-T-H-I-N-G. Correcting misconceptions shouldn’t pit us against them.

Rule number one: Don’t flat out tell them they are wrong.

If we just point out faulty understandings, our words will likely fly in one ear and out the other. Rather, we need to guide students through a process for them to replace mistaken information. We can begin by making sure students are being heard.

Start by pre-assessing a concept. It could be a quick Google Form question, a journal response, or an entrance ticket on scrap paper. Giving students time to recall and write down prior understandings is like opening a file cabinet in a student’s brain.

And it’s important for students to overtly record their previous knowledge so they have something tangible to compare with their post-learning reflections. Even if initial impressions are inaccurate or incomplete, don’t discount them!

Leading students to aha moments won’t happen by solely putting a text in front of them. Nor will a teacher-directed lecture or lab demonstration. Students need to go through the messy (and sometimes uncomfortable) learning process of grappling with concepts that challenge their previous thinking.

We need to help them build bridges between old and new understandings and make lasting connections. Simply put, we teach them to learn how to learn.

Take Science Class, For Example

A helpful strategy to use when designing science lessons is what Joan Lucariello and David Naff (2015) call Predict-Observe-Explain (P-O-E). It begins with the teacher strategically planning a class demonstration to target expected misconceptions.

Before beginning the activity, give students time to make predictions. Then conduct the demonstration while students actively observe. Since students don’t perform the experiment themselves, more brain power is freed up for them to compare their observations to their initial predictions.

This comparison process kickstarts the time for self-repairs to begin and true learning to occur. After the demonstration, students revisit their prior knowledge notes and explain why their observations conflicted with their predictions. Focusing on why right IS right is key.

An added benefit is to issue advance notice at the start of a lesson. Tell students to be on the lookout for explanations that may differ from their own. Here’s an example:

A PBS.org article (2013) highlights a science experiment where students illustrated and explained a marble’s path before it rolled off a tabletop (prediction). The instructor advised students that if they had certain preconceptions during the pre-assessment, they might want to focus extra attention on these concepts during the actual experiment (observation).

Students who were forewarned with these instructions showed noticeable improvements in absorbing information that conflicted with their existing knowledge and describing why the marble acted the way it did (explanation).

Activate Metacognitive Thinking

Misconceptions matter. All new learning is analyzed and viewed through the lens of prior understandings. Nothing will change until students can actively engage in learning situations and reflect on the discrepancies themselves. Just spotting them isn’t enough.

When students encounter cognitive conflict, we need to help them resolve it productively. Here are some ways we can do that:

- This, Not That

I learned the value of this strategy when I discovered I was doing an exercise incorrectly during my workout routine. A hammer curl is a hammer curl, right? Nope. After modeling the correct form, the gym instructor showed me what not to do. Immediately, I questioned my technique. The incorrect (and less safe) form I had been doing became clear when I saw the difference between right and wrong.

This strategy isn’t exclusively for physical education teachers. In a step-by-step manual to learn calligraphy, the author showed each letter’s correct form, followed by detailed instructions for creating the stroke. I grabbed my paper, ink, and pen, and crafted what I thought mirrored the model. Then I read the author’s notes and dissected her models of incorrect letters. Once again, my errors were clear to me when I compared the proper and improper strokes she provided.

Math teachers may find this strategy helpful for students to see the difference in place value formats when writing equations. Literacy learners could evaluate models of literal versus deeper critical thinking questions to enhance the quality of their book club discussions.

Most importantly, give students time to compare this and that, revise with scaffolded support, and apply the skills independently.

- Examples and Nonexamples

Our brains like to generalize and group similar concepts together. Each new bit of learning is like a puzzle piece that fits together with other pieces to form our understanding of a concept. This goes awry when you overgeneralize and connect an example that doesn’t apply.

Conversely, undergeneralizations also result in knowledge gaps. To correct these misconceptions, Connie Malamed (2021) suggests allowing students to interact with a set of examples and nonexamples. Our pattern-seeking brains will enjoy the inquiry-based explorations.

This strategy could be used to help students deepen their understanding of vocabulary. Here’s an activity for the word contentment:

Which would be an example where contentment may be used? Explain your reasons.

• Enjoying a good movie with friends at the end of a school week?

• Missing a chance to hang with friends because you have to babysit your siblings?

The best path to true understanding is for students to generate their own examples of a word or concept. Then they’ll know if they still need to clarify any fuzzy areas. Once you have to teach it to someone else, you’ll discover if you truly understand it!

- Graphic Organizers

Charts, webs, maps, and diagrams offer students a tangible place to organize the knowledge they activate before, during, and after lessons. K-W-L Charts and Venn Diagrams are storehouses of information students can reference to confirm or rethink prior knowledge and relate new concepts to old. Also, Frayer Models are organizers which incorporate examples and nonexamples. By documenting ideas throughout the learning process, students can visibly see progression toward mastery as they refine their understandings.

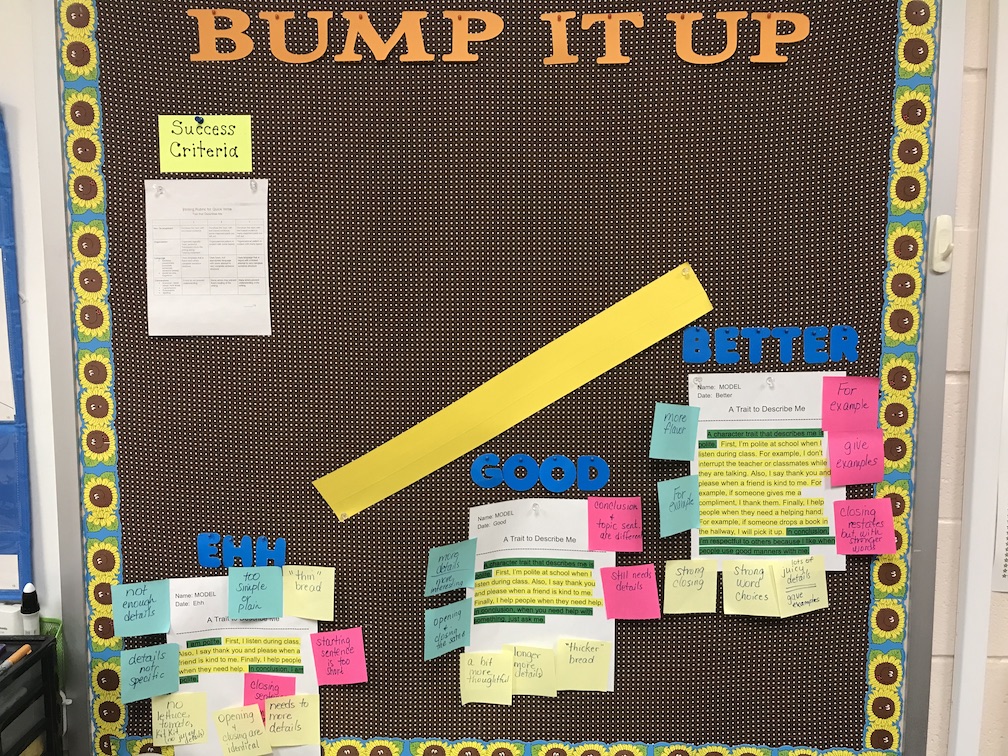

- Bump It Up Bulletin Board

Knowing student writers have been incorporating text evidence since elementary school, I anticipated misconceptions about what constituted high quality evidence. Formative writing samples confirmed it. As a result, I created this bulletin board to show different ranges of supporting evidence. The sticky notes show students’ reflections after comparing ehh, good, and better examples to the success criteria. This experience transformed student writing because they internalized what it meant to include detailed text support in essays.

Students Learn through Their Mistakes

Drop breadcrumbs to lead students to clarify understandings on their own. By highlighting the continuum of learning, students realize through a self-discovery process that they just aren’t there … yet. When students own this metacognitive process, there’s no need for you to be the almighty sage on the stage and sole keeper of knowledge. Guide from the side as students experience the joys of learning and growing.

References

Lucariello, J., & Naff, D. (2015, March). How Do I Get My Students Over Their Alternative Conceptions (Misconceptions) for Learning? American Psychological Association.

Malamed, C. (2021). Six Ways to Use Examples and Nonexamples To Teach Concepts. The eLearning Coach.

PBS. (2013, April 24). The Science of Smart: How to Unlearn Mistaken Ideas. PBS.org.

Kelly Owens is a literacy interventionist who helps middle graders overcome past literacy struggles by building stamina, confidence, and a greater love of learning. As a teacher with over twenty-eight years of experience, she has proudly represented Hillsborough Township Public Schools as a NJ Governor’s Teacher of the Year.

Kelly also co-created Buddies for the Birds, which was featured on Emmy Award-winning Classroom Close-up NJ. Kelly earned her Ed.M. from Rutgers University. Additional writing credits include published work with The King School Series (Townsend Press), The Mailbox magazine, and MiddleWeb.