Using Dystopian Fiction to Explore Citizenship

This article about a major project exploring citizenship through dystopian fiction and a study of whistleblowers was first posted in August of 2015. Links and bio material have been checked and updated. (3/5/25)

By David Sebek

The 2013 image is iconic. Edward Snowden, pale and unshaven, sitting in a bright, mirrored hotel room, attempts to explain to the world why he leaked classified information from the United States National Security Agency.

His soft spoken plea for understanding lasts twelve minutes and thirty-five seconds and has more than three million views on YouTube. The interpretation of his actions is polarizing, his place in the historical timeline debatable. How will he be remembered? A hero or a traitor?

But defining ambiguous concepts like citizenship requires an inductive approach, one where we need to look at many examples in order to define the concept, and more importantly, how each student applies it to their own lives.

I’d like to consider several questions here: How do we approach a definition of citizenship in our classrooms? Where do we find the examples of citizenship in question? What are the criteria we use to evaluate a person’s actions in terms of citizenship? And how does citizenship connect to the massive interest in dystopian fiction among today’s middle schoolers?

Defining Citizenship

Citizenship is not clearly defined in many standards (Common Core or State Level), but in the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills teachers are given some guidance in the 2nd Grade Social Studies Objective: identify characteristics of good citizenship, including truthfulness, justice, equality… responsibility in daily life…

Using these four concepts as a guide (truth, justice, equality and responsibility), students might construct criteria for evaluating the actions of others in relation to citizenship. Unfortunately these are slippery words – abstract terms that vary among cultures and resist applicable definitions in real world contexts.

Even in middle school, I’ve found that picture books can provide a shared experience and opportunity for class discussions or socratic seminars on these four components of citizenship. Some examples:

Johnny Express on YouTube. This comedic and tragic look at a futuristic delivery man can also augment the responsibility discussion, as we evaluate actions in terms of whether they are responsible or selfish, at various levels of awareness.

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cSGZyRBpMBE&feature=youtu.be]

Equality: It’s not a video or picture book, but the short story “Harrison Bergeron” by Kurt Vonnegut hooks readers with a memorable opening line: THE YEAR WAS 2081, and everybody was finally equal. After reading the story (here’s a reading at YouTube), I set up a simulation where I tell students that their grades have been equalized; everyone in the class is going to earn the class average this grading period. Some students rejoice and some rage.

I let students express their dislike for this idea and why they are so opposed and they point out that everyone in the class will stop trying. I counter by saying America was built on the ideal that “all men were created equal.” The usual pushback is that we have equal opportunities, but taking advantage of those opportunities is up to the individual. This is a fairly simple interpretation, and at higher levels the ideas of equal opportunity and equity could be explored at a deeper level.

Students synthesize these four concepts into a working definition of citizenship. They combine the four terms to describe what they believe to be a productive citizen.

Citizenship (and Dystopia) in Action

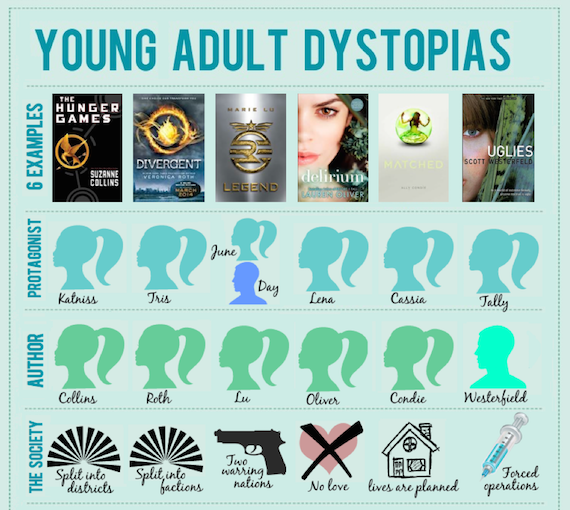

Students need case studies to test and evaluate their definitions of citizenship. This is where literature, and particularly the explosive rise of YA and other dystopian literature , is an ELA (or social studies) teacher’s best friend.

What’s the appeal of dystopian literature? Students love the what if. What if we lose control of this fragile egg we call society? The connection between dystopian literature and the students is that they imagine themselves in these futuristic worlds and test the waters of “Wow, could this really happen?”

In living vicariously through these scenarios, students might (depending on current events in their world) also take a measure of how well they have things compared to the protagonists, while secretly expressing their angst and rebellion against authority figures like teachers and parents. (Springen, 2010).

And in these worlds lives the dystopian protagonist, the character whose actions the students are going to place on trial, to evaluate and ultimately decide how the character’s deeds should be remembered.

In analyzing the actions of various dystopian protagonists, students build a character traits chart that displays many of the common characteristics of the dystopian protagonist. This chart becomes very important as they apply their work to historical situations later.

The common dystopian character traits are:

- often feels trapped and is struggling to escape

- willingness to accept legal punishment for their actions

- believes or feels that something is terribly wrong with the society in which he or she lives

- faces oppressors much more powerful than they are

- faces utter defeat or sometimes Pyrrhic victory

- helps the audience recognize the negative aspects of the dystopian world through his or her perspective.

I do not give students these traits upfront. As we work through various forms of text they look for the patterns and commonalities and build a list similar to this through their investigation of the actions of various characters in various dystopian settings.

Begin with Videos

When starting something new, like character analysis, I try to redistribute the cognitive load on the students so that they can focus on the new process with easier text. In this case, I start with video clips because the cognitive load is more on the analysis, rather than the interpretation of written text. As students master the process, I will redistribute the cognitive load so that there is analysis of written text.

Here are three great short videos (and one brief movie) to start the process of analyzing the actions of the dystopian protagonist. (If you have problems with link clicking, copy the links in brackets.)

The Scarecrow by Chipotle Grill

- [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cpp8Xpn7hEo]

- Routine Republic by Taco Bell

- [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o4MH4hapxaM]

- The 1984 Apple Super Bowl Commercial. You may want to print out the voiceover for this commercial because parts are hard to hear,

- 2081: Film Adaptation of Harrison Bergeron. It’s a 25-minute film that tells the story “surprisingly well.”

After watching videos I bring in text via musical lyrics that students analyze for the voice of the dystopian protagonist. Songs include:

- Uprising by Muse

- Won’t Get Fooled Again by The Who

- The Trees by Rush

- Radioactive by Imagine Dragons

You might substitute songs with similar messaging more familiar to students.

Evaluating the Actions of Others

Once students establish the traits of dystopian protagonists, we revisit Harrison Bergeron. This time, as students look at the text, we ask them a broader question: based on Harrison’s actions as a dystopian protagonist and using your definition of citizenship, is Harrison a hero, traitor, rebel or revolutionary? Please use text evidence to support your answers.

After this analysis, discussion, and opportunity to revise personal definitions of citizenship, students can now extrapolate their knowledge to a historical whistleblower.

You could share with students names from the Wikipedia entry on whistleblowers or go to whistleblowers.org and begin researching, analyzing and evaluating the actions of whistleblowers and their role in history and how we should judge their actions in terms of citizenship.

If your students need a little more scaffolding with the process, you could visit the documentary The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers produced by PBS (see the trailer here) – the full feature available on Prime).

To begin the whistleblower exploration, students might look at these questions:

- What problem(s) influenced the actions of the whistleblower?

- What was the whistleblower trying to resolve?

- What conditions led to this problem or event?

- What were the effects of the actions of the whistleblower?

- What is the significance of this event?

- What are some ethical issues surrounding the consequences of what the whistleblower did?

- Why is this issue so paradoxical to citizens in _________________?

What happened over time that would cause a person to…?

- What do you wonder about? What are you puzzled by?

- What concerns you about the actions of the whistleblower?

- What issues does the whistleblower want us to be aware of?

- What should we be investigating?

- What are the consequences of it?

- What is the reaction over time of the whistleblower’s actions?

- What big ideas influenced the whistleblower’s decisions?

- What patterns influence the behavior of the whistleblower?

The students argue that the whistleblower they chose to study is either a hero or a criminal. And they use their understanding of justice, equality, responsibility and truth to justify their analysis. The final product can take a number of different forms but has to address these key questions:

- What are the responsibilities of individuals who encounter disturbing information that they consider damaging to those in power?

- When is it justifiable for an individual to go public with certain information?

- What is the society’s right to know versus the controlling agency’s right to secrecy?

- When does a claim of justice supercede a promise of fidelity?

The students create a plea for understanding for either the whistleblower or the society. Their job, using their evidence and definition of citizenship, is to explain why the whistleblower is a hero or a traitor.

Citizens with a conscience

Teaching is a hard job because the work is never finished. On the final day of school, when the last student hugs you goodbye and your room is an echo of memories, you realize that although those students have moved onto the next grade, their learning is not finished. They remain eternal works in progress, moving on to the next step of their transformation, from dependent children to independent, productive members of our society.

As a teacher, the best you can do is hope that the time you spent with your students will help them in America’s future, that their conscience has grown, that they will work to impose their free will in building their lives, and that, most importantly, they will take action when they know something is wrong.

ALSO SEE HERE AT MIDDLEWEB:

Dina Strasser’s “Speculative Fiction for the YA Classroom”

When this article was written in 2015, David was teaching middle school in Missouri City, TX, the same year his co-authored book Stand Up! Speak Out!: The Social Action Curriculum for Building 21st-Century Skills (Prufrock Press) was published for grades 6-8.

Learn more about David’s current work at his LinkedIn page.

What happened over time that would cause a person to…?

What happened over time that would cause a person to…?

David – this is brilliant! Thank you for the wonderful resources and your focus on the citizenship part of civics education blended with ELA!

Thank you Frank. Literature offers so many varied opportunities to help our students grow.

David,

What an amazing and provocative discussion framework! Relevant, broad-minded, and culturally literate to foster powerful thinkers. I’m passing this along to all of my ELA and SS colleagues.

Thank you Steve, I appreciate you passing these ideas on to others.

Excellent ideas that are relevant outside of the US as well! I will share with my education connections.

Thank you Catherine. I agree that there is a much larger cultural component that could come out of discussions like these.

Thank you for your article. We read and discuss The Giver with our 8th graders, and it sparks some lively discussions! The Giver movie is terrible, but the novel is wonderful and throught-provoking.

Good evening Sandra,

Jonas is a great example of a Dystopian Protagonist. Nice place to start conversations about the role of a citizen in a society.

This also can be connected within the History curriculum to the issue of civil disobedience and the Civil Rights movement. The danger is always that we bias the discussion in favour of good examples of law-breaking… and kids (and their parents) get the wrong idea. Ultimately the only “right” type of civil disobedience is when it turns out you are on the side of justice.