Helping History Students Regain Common Ground

A MiddleWeb Blog

It’s an understatement to say that being in class since the presidential election has required extra sensitivity toward the views of all students.

Each day, I find myself looking at the news article we are about to discuss through a prism of questions.

- Is this from a reasonably neutral source?

- Is this an article that can be discussed in a bipartisan way?

- How can I discuss this topic without offending students on the right, left, or in between?

- Should we just skip talking about politics for the day and look for other news instead, as with these fascinating images on Black Sea archaeology I showed last week?

from New York Times story: “A photogrammetric image of the stern of the Ottoman-era ship showing coils of rope and a tiller with elaborate carvings. A lack of oxygen at the icy depths of the Black Sea left the wrecks relatively undisturbed.” Credit: EEF/Black Sea MAP

Some days, even a battery of such screening questions doesn’t prevent metaphorical blood on the table, as students quickly get riled up about the actions of one political party or the other.

That’s why one recent eighth-grade history class felt so liberating. With civil discussion about a current and then a historical topic, students reminded me of a tool we history teachers can pull out even during the most difficult conversations: We can ask students to shift their perspective, to adjust their lens.

They can imagine the opinion of someone on the other side. They can learn more information and analyze how these additional facts shape their view. They can watch their beliefs evolve even while expressing an opinion they thought they held.

Hamilton Raises Questions of How to Protest

We started with a topic I enjoyed both because it involved one of my favorite musicals and because it had two interesting sides.

On the night that Vice-President Elect Mike Pence saw Hamilton: An American Musical, a cast member read a statement addressed to Pence at the end of the show, urging Pence to “uphold our American values and to work on behalf of all of us.” The next day, President-Elect Donald Trump tweeted asking the show to apologize for being rude, while Mike Pence talked on Fox News about how “this is what freedom sounds like.”

With the students I showed two clips, the original statement from Hamilton and the follow-up interview on Fox News with Chris Wallace interviewing Pence. Afterward I asked them to write for 4-5 minutes about their opinion.

Was it rude for the show’s cast and producers to call out Pence like that, when he was just trying to enjoy the show? Was such a statement simply an appropriate expression of the actors’ First Amendment rights? Was there another way to convey the message?

Students then shared their responses with a partner so that they could see the diversity of opinions represented.

The students were deliberative, weighing both sides even if they came down on one. As my student Bradley wrote, “It was an okay message, but not the appropriate venue to say it…. Wrong time, right message.”

Students’ opinions also changed based on additional information they heard through the course of the videos and discussion.

Silas reflected, “At first, I didn’t think the cast of Hamilton was rude at all. I thought they were just acknowledging Pence. Then I let their words and Mike Pence’s thoughts sink in. I realized that saying that then and there wasn’t the politest. I feel that Pence didn’t deserve the rudeness at all.”

Through one current event, we had touched on how and why people protest and where are appropriate places and times to do so. Unlike during the previous week, when some students were up in arms about Trump’s Cabinet choices, this was an article that addressed politics in a palatable way.

Jumping Back to Jefferson

Coincidentally, my main lesson plan for the day involved another discussion about appropriate behavior. This one was far more serious: the contradiction inherent in Jefferson’s owning slaves while also being the primary author of the Declaration of Independence.

To dive into this topic, the eighth graders had read an essay for homework called “A Luxury We Can’t Afford: Thomas Jefferson and Slavery,” from an excellent book by Alan L. Lockwood and David E. Harris, Reasoning With Democratic Values: Ethical Problems in United States History.

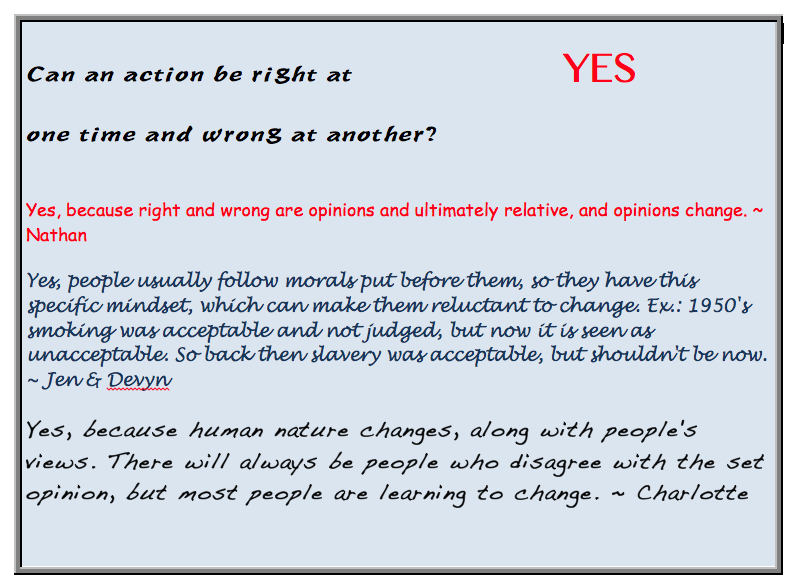

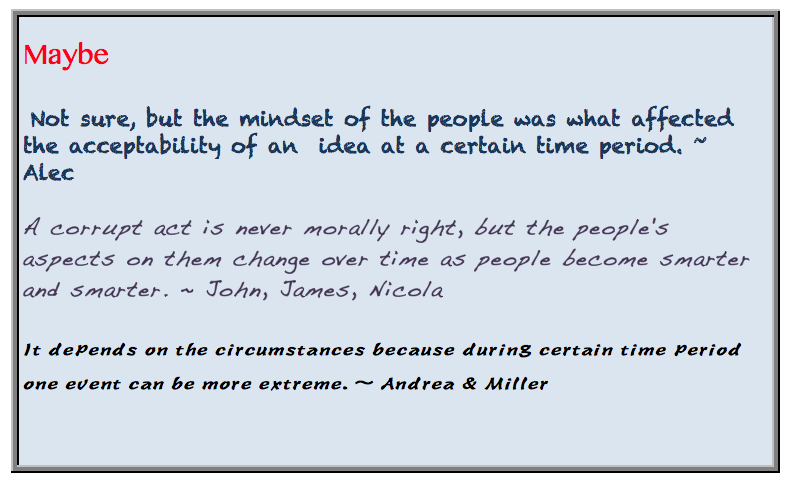

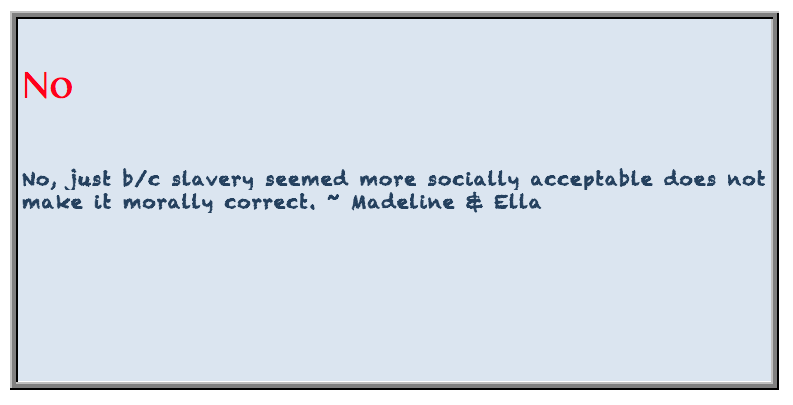

Each student had answered a question from the text: “Some have argued that it might be wrong to own slaves in the 20th century, but that during the 18th century it was morally acceptable. Can an action be right at one time and wrong at another? Explain your thinking.”

After the Hamilton discussion, students shared their responses in pairs to the homework question and then wrote at least one argument on the board for everyone to see – categorized under Yes, Maybe or No. After giving the caveat that I understood no one was arguing that slavery has ever been ethical, I asked students to explain their ideas.

Even those who landed firmly in Yes or No saw the arguments of the others, with almost everyone eventually supporting the idea that society shapes our views, but that individuals can stand up for what is morally right, if they realize it.

As Jazzy wrote in her response, “I believe that an action can’t be right at one time and wrong at another, especially slavery. Over time, more and more people start to realize what is actually happening and start to build more sense. Often times, bystanders are usually the ones to understand the mistake of the action, not the person who’s doing the action.”

What Made This Class Work While Others Didn’t?

As opposed to other post-election discussions of current events that had made me cringe because I felt a level of vitriol simmering just beneath the surface, this class reaffirmed my faith in gracious conversation and dialogue among middle school students.

So, what did I do to shape this discussion that I hadn’t done in other recent post-election discussions? In other words, how could I try to recreate this success in the future?

- Pick topics with substantial middle ground where people can meet, think and compromise.

- Acknowledge that different views will exist, and we want to hear all of them.

- Pair a relatively light news topic with a heavier historical topic. It’s often easier to moderate our passions when we are discussing something in the past.

It worked once. I’m crossing my fingers that, with careful choices of topics and a discussion focused on finding common ground, it can happen again.

Outstanding lesson!

Thank you, Mary! That means a lot coming from you.

This was an outstanding lesson! You did not present your opinion and simply stated facts. The students were then asked to form their opinion based on what was presented.

If we are unable to have such discussions then what is the point of a liberal arts curriculum. Just to teach facts?

Please send another column.

John, thanks for reading and for your points about holding balanced political discussions. I appreciate it!