The Teaching Practices That Work Best for Me

After teaching for almost 16 years I’ve become a little more skeptical.

Perhaps it’s more accurate to say I’ve become more confidant about my own judgment. I’ve realized there is nuance to teaching and every practice won’t work for my teaching style, and even if it does it won’t work all the time.

Conversely, there are practices that are generally frowned upon that I think can be effective. When I go on teacher twitter I often see posts where people are talking about how terrible a teaching practice is, and lots of people will agree how terrible it is, and I’m thinking that it’s not that bad, and that I do exactly that sometimes.

For a long time, I found this really disheartening. It made me feel like a failure.

Over time, I’ve realized that I’m the teacher in my classroom, I know my classes and my teaching style, and I’m the one in the position to decide what is best for my students.

I still get on Twitter, and I get a lot of benefit from it, but I allow for the fact that my opinion can be different and still be valid. I’ve also become more skeptical of sweeping statements, such as “you should never do…” or “you should always do…”.

Working in Groups is Not Always Productive

In recent years I have felt a pressure to make sure my students are frequently working in groups. I feel better when I have my desks arranged in groups, because I think it looks better to observers. I’m not proud of this, but I’ll admit I have kept students in groups past when it was productive because I thought it looked better.

There are several reasons why I have personally found that students working in groups is not always the right choice. Not often but at times, the students do not have the maturity to work with other students and no matter how much coaching or team building we do, it is not going to be successful.

Perhaps it’s different in middle school, but high school students who have not worked in groups in previous years can find it hard to make the adjustment when they are in 10th, 11th or 12th grade. In that case, working in groups becomes such a distraction it impedes their learning.

In cases like this, I prefer smaller bursts of cooperative learning such as turn and talks where students lean in and talk to their classmates for shorter periods.

Also, the concept I am teaching has a lot of bearing on whether I want students in cooperative learning groups. When I am teaching a new concept, I prefer my students in rows. I want to lay out clearly and concisely the concept I am introducing. I prefer cooperative learning as a means to reinforce concepts as opposed to introducing them.

Direct Instruction Can be Effective

Related to the above topic, I have found that direct instruction can be effective. There was a time when I felt guilty going to the board and giving direct instruction.

In fact, direct instruction can be very effective when it is well thought and logically presented. There are students who are much more comfortable with direct instruction as opposed to discovery or exploration activities with other students.

Sometimes Tricks Are Okay

In math, there are words or phrases that have been adopted that are shorthand for math processes. These words or phrases are commonly thought of as tricks and are frowned upon.

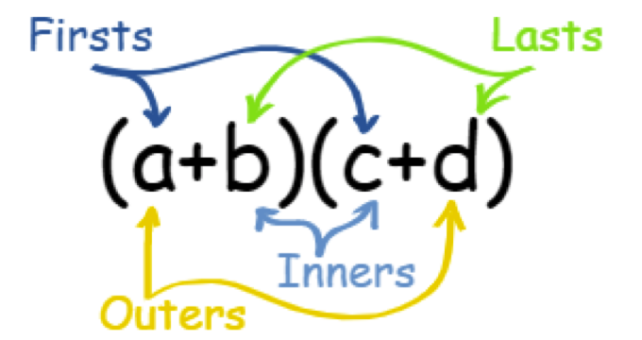

I was once firmly in the camp of “no tricks!” In the math world, FOIL is probably on of the most popular memory tricks used. FOIL is a term math teachers use to remind students how to distribute when multiplying two binomials. It stands for First, Outer, Inner, Last.

Among many teachers FOIL is considered to be a “bad word.” I recently did a search on Twitter and immediately found several threads suggesting that FOIL should never be used in a math classroom. I get it. Students need concepts not tricks. But I think even here, a nuanced approach is probably better. For some students, a mnemonic such as FOIL can be helpful. It can be discussed after teaching distributing to help reinforce the idea of distribution.

After years of avoiding the term at all costs, I mentioned it in my classroom recently after teaching the concept of distribution. Most students were unimpressed, but a few found it helpful. In my opinion, it helped those students realize and remember that they need to distribute four times, and a common mistake is to only distribute the first and the last terms.

While I agree a sound math foundation is based on concepts, in reality there can be room for easy-to-remember phrases or “tricks” that help students recall the nitty gritty of the processes.

What is a Best Practice?

When it comes to teaching math “the right way,” I give myself more latitude than I used to. Using my judgment and experience, I try to address these questions when I am planning my instruction:

- Have I presented the math concept logically and in a way that makes sense for students at this point in their math journey?

- Have I given them a sound enough foundation that they can ask their own questions?

- Have I avoided shortcuts that would pay dividends in the short term but would sacrifice their long term learning?

I try to answers those questions truthfully, and if a practice can fit into that framework, I am okay with it. And if a practice doesn’t further their mathematical foundation, then I don’t want to do it, even if it widely considered best practice.

What are some best practices that work for you? What are some best practices that you haven’t always found successful? I would love to hear your responses!

I agree with all you’ve said. As teacher, you are expected to know your students best and what is best for them, with few exceptions. One of these is that your assessments/perceptions are without any bias [and not just racial, gender, intellectual]. Another is that your lessons are well thought out in considering the level of information shared, esp. when illustrating the past.

I do believe that it is in the classroom where the teacher needs autonomy, voice and support in doing what’s best for students and with the support of families. Truth can be taught tactfully. That’s my take.