Value and Success Can Build Student Motivation

By Barbara R. Blackburn

Would you like your students to be more motivated internally? Intrinsic motivation has two foundational elements: People are more motivated when they value what they are doing and when they believe they have a chance for success.

Although you can’t provide either of these for your students, there are several key building blocks that support each.

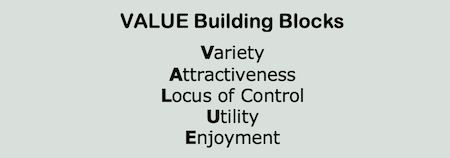

Building Blocks for Value

First, students are more likely to be intrinsically motivated to learn if they value what they are asked to do. There are five building blocks to add value in your classroom.

Students are more likely to be motivated when they are not asked to do the same thing over and over again. What is your least favorite routine task? I hate paperwork. It doesn’t matter if it’s completing a travel form for reimbursement or organizing my tax records, I would rather do almost anything else.

One day I realized that if I had to do paperwork every single day, over and over again, I would be miserable. That, however, is exactly how our students feel about some classes. There is an element of work involved in learning, but when students view learning as drudgery, they are less likely to be motivated to work. When we add variety – when we avoid doing the same thing day after day – we provide an antidote to drudgery.

Variety is enhanced when you make a lesson attractive. Attractiveness doesn’t mean adding fluff to a lesson; it means integrating elements of curiosity and originality into what you teach. Charlene Haviland, a teacher in Norfolk, Virginia, has developed lessons that incorporate this concept.

Variety is enhanced when you make a lesson attractive. Attractiveness doesn’t mean adding fluff to a lesson; it means integrating elements of curiosity and originality into what you teach. Charlene Haviland, a teacher in Norfolk, Virginia, has developed lessons that incorporate this concept.

For example, she has used the Harry Potter books to teach science concepts. For a discussion on the flying broomsticks used in the game of Quidditch, Haviland said, “We can even go into Bernoulli’s principle and explore how we can take that from flying on a broom to…how airplanes work…and why some fly better than others.” (Spellbinding Science: An Interview With Charlene Haviland. Curriculum Review, v45 n1 p14 Sep 2005. Accessed May 8, 2024: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ726405)

I don’t know about you, but I’d sign up for that class quicker than I would a standard class on aerodynamics.

The third building block, locus of control, refers to how students need to feel as though they have some control or choice in a given situation. This basically means that if Kinu feels trapped and like she is following orders, she is less likely to be motivated. Students are more apt to be intrinsically motivated if they have ownership in the learning – if they believe they are a vital part of the learning experience, rather than simply being told what to do.

Students also need to see the utility in learning. When I do workshops with teachers, I know they come into my session with one burning question: “How can I use this information immediately?” Adult learners are juggling so many demands, they prioritize activities and their attention based on how well something meets their immediate needs.

Kids are similar, except they don’t have the choice to leave the room. So often we forget to show students why they need to know what we are teaching. I was observing a student teacher when a student I’ll call Darin asked, “Why do we need to learn this?” It clearly flustered her, particularly because I was there to observe her, and she snapped back, “Because I said so.” You can imagine the look on Darin’s face.

Kids are similar, except they don’t have the choice to leave the room. So often we forget to show students why they need to know what we are teaching. I was observing a student teacher when a student I’ll call Darin asked, “Why do we need to learn this?” It clearly flustered her, particularly because I was there to observe her, and she snapped back, “Because I said so.” You can imagine the look on Darin’s face.

Her answer ranks right up there with “Because we have to. It’s on the test.” Neither helps students understand why learning is important. Students are more engaged in learning when they see a useful connection to themselves.

The final block for building value is enjoyment. Students are more motivated when they find pleasure in what they are doing. During my first year of teaching, another teacher told me two things: “Don’t smile before Christmas; and if your kids are enjoying the lesson, you’re doing something wrong.”

Now I realize how unhappy she must have been. Although you need to have a classroom with structure and order, that doesn’t require a “prison camp” atmosphere. It is absolutely, positively okay to smile and have fun. Play games, make jokes, do something fresh and different.

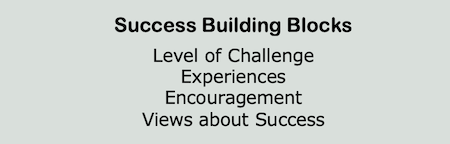

Building Blocks for Achieving Success

Students are also motivated when they believe they have a chance to be successful. And that belief is built on four additional building blocks.

First, the degree of alignment between the difficulty of an activity and a student’s skill level is a major factor in self-motivation. The level of challenge needs to be right. Imagine that you enjoy riding a bicycle, and you have competed in a local race. Now you have the opportunity to compete against five-time World Champion Hannah Roberts for a spot on the US 2024 Olympics BMX team. How do you feel? There’s plenty of opportunity for challenge – too much challenge!

Or perhaps you love reading novels, but the only language you can read is Russian. How motivated will you be in an English literature class? For optimal motivation, the activity should be challenging but in balance with your ability to perform.

That’s a struggle for many teachers, but that is the foundation of our jobs as teachers – starting where a student is, and moving him or her up to increasing levels of difficulty, providing appropriate scaffolding for learning at increasing levels.

A student’s past experiences are also an important success factor. I’m more likely to believe I can be successful in science if I’ve been successful in other science activities. On the other hand, if I’ve had multiple negative experiences doing a lab, I’m less likely to want to try a hands-on experiment because I don’t think I can.

A third building block to feelings of success is the encouragement a student receives from others. Encouragement is “the process of facilitating the development of the person’s inner resources and courage towards positive movement” (Dinkmeyer & Losoncy, 1980, p.16).

Encouragement is not praise. The difference is simple: praise focuses on the performance of a student and is a form of extrinsic motivation; encouragement recognizes the student’s worth based on simply being present and capable of learning.

When you encourage, you accept students as they are so they will accept themselves. You value and reinforce attempts and efforts, and help the student realize that mistakes are learning tools. Encouragement says, “Try and try again. You can do it. Go in your own direction, at your own pace. I believe in you.” Encouragement can be in the form of words, but you can also provide encouragement through a consistent, positive presence in your students’ lives.

Finally, it’s also important for students to develop a nuanced view of success. They need to read and learn about people who failed before they succeeded because the final building block is a student’s views about what it means to succeed or fail. Many students see failure as the end rather than as an opportunity to learn before trying again. How they define success and failure drives many of their beliefs about their own ability to accomplish a task or overcome a challenge.

Whether you use examples of actors or musicians who failed first, or you share the story of Steve Jobs who was fired from Apple before he came back to invent the iPhone, your students need to learn that success seldom comes immediately. In addition to learning about real people, reading novels that focus on resilience can help your students learn about persevering to success.

A Final Note

Although we cannot make students be intrinsically motivated, we can create an environment that includes the critical elements of value and success. When we do, students are more likely to be internally motivated.

Dr. Barbara R. Blackburn, a “Top 10 Global Guru in Education,” is a bestselling author of over 30 books and a sought-after consultant. She was an award-winning professor at Winthrop University and has taught students of all ages. In addition to speaking at conferences worldwide, she regularly presents virtual and on-site workshops for teachers and administrators.

Dr. Barbara R. Blackburn, a “Top 10 Global Guru in Education,” is a bestselling author of over 30 books and a sought-after consultant. She was an award-winning professor at Winthrop University and has taught students of all ages. In addition to speaking at conferences worldwide, she regularly presents virtual and on-site workshops for teachers and administrators.

Barbara is the author of Motivating Struggling Learners: 10 Ways to Build Student Success (Routledge/EOE, 2015) and many other books and articles about teaching and leadership. Visit her website and see some of her most popular MiddleWeb articles about effective teaching here.