Let Them Read Whole Novels!

This article by 8th grade ELA teacher Ariel Sacks is adapted from the opening pages of her 2013 book Whole Novels for the Whole Class: A Student Centered Approach (Jossey-Bass/Wiley), framed by the publisher as “a student-centered literature program that promotes critical thinking and literary understanding through the study of novels with middle school students.” We’ve browsed the book and find it’s a rich mix of what, why and how, including nearly 50 pages of lesson materials in the appendices. See our review here.

Stories are interesting; there’s no question about it. We are “the story-telling animals,” Jonathan Gottschall shows us in his fascinating book, The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human (2012). We live for the stuff of stories!

We have an innate drive to experience and tell stories; they are part of how we think and relate to the world every moment of our lives. Stories are also an important piece of how our brains learn and remember. Dan Willingham, author of Why Don’t Students Like School? A Cognitive Scientist Answers Questions about How the Mind Works and What It Means for the Classroom (2010), explains: “The human mind seems exquisitely tuned to understand and remember stories—so much so that psychologists sometimes refer to them as ‘psychologically privileged,’ meaning that they are treated differently in the memory than other types of material” (66–67).

Later, Willingham notes that in psychological experiments, stories were consistently rated more interesting than any other presentation format, even if the information was the same.

And yet we also have a widespread problem across the United States of students not wanting to read—not even stories. Kelly Gallagher, author of Readicide (2009), believes the problem has reached a point of “systemic killing of the love of reading” (2), and I can’t say he’s wrong. The coexistence of these two opposite realities suggests one thing to me: when students are asked to read fiction, and this mostly happens for them in school, they aren’t really experiencing the stories.

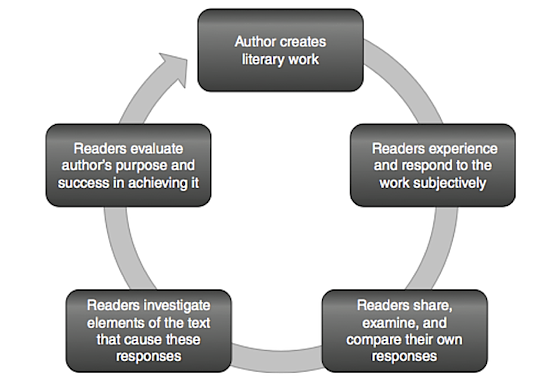

This flow chart shows how

the interaction between student and text

works in the whole novels program,

leading to critical analysis of the work.

Why my students read the whole novel first

Imagine going to see a movie in the theater. You’ve heard good things about this movie, and you feel that special movie theater excitement when the lights go down and the movie begins.

After the second scene, the movie stops. The lights come on, and someone at the front of the theater with a microphone starts asking people what they think about the movie. Why do you think the director made this movie? What is motivating the characters? How will it end? The person in the front then begins taking people’s comments about the movie so far.

You try to listen, but you were much more interested in the movie itself than in what random people in the theater think about it. The person at the microphone starts talking about how one of the characters in the movie reminds her of herself when she was young.

Someone next to you whispers, “I don’t care what these people think about this right now. I came to see the movie!” The two of you begin chatting about other things in an effort to kill time until the movie resumes. Finally, the person in front says, “Well, that’s all the time we have for today. Come back tomorrow, same time, same place, to see the next scene!”

Now consider another scenario. You’ve just seen a really interesting movie in the theater. When it finishes, the lights come up, and someone in front of the theater with a microphone explains that there will be a brief break during which people are encouraged to visit the concession stands. Then people are invited to discuss the film in special rooms in small groups.

The theater will even have the ability to rerun certain scenes, such as the opening scene, to spark discussion. You happen to have an hour to kill until you need to move to your next commitment. Would you consider participating in such a discussion?

The whole-novels method builds on the reader’s interest in experiencing the story in its entirety by allowing students to read the book from beginning to end before formal discussions of the work begin. Adult book clubs use the same structure: members usually take a month or so to read on their own time and then come together to discuss the entire book. College seminars work the same way, using a faster pace of about a week to read a book.

In my experience, that is not the typical process in k-12 education. I have spent time in many different English language arts classrooms in public, private, and charter schools in New York City, and I have very rarely seen students read an entire novel before being asked to speak or write analytically about it. The standard for whole class novel studies in both traditional and progressive classrooms seems to be that students read and discuss the books chapter by chapter.

Why not discuss the novel chapter by chapter?

The chapter-by-chapter model parses up the reader’s experience in a way that takes a lot of the pleasure out of the process and can even interfere with comprehension. The story is a piece of art that is intended to be experienced as a whole. If we were reading a collection of short stories or poems, we could naturally discuss each story or poem. But a novel is a longer form created to allow readers to more deeply enter an elaborate world the author has developed. The power of the novel comes from the time we spend in these worlds with the characters, experiencing the conflicts, the symbols, and the author’s unique style of prose.

Simon Lesser (1962), a psychologist and literary critic who studied and wrote extensively on the psychological impact of literature, explained that in order for a reader to become captivated by the world of a story, “the indispensable condition of such an experience, and the first stage of the experience itself, is a relaxation of the vigilance usually exercised by the ego. A willing suspension of disbelief, a receptive attitude, is essential not only to the enjoyment but even the understanding of comprehension.”

When adults read, we allow the author to guide us with nothing but the work of art he or she created. We need to help students develop that special relationship with a text rather than trying to be a third member of the relationship—especially since we are authority figures for students, and they are conditioned to look to us for answers and interpretations. We need to step away to allow genuine interaction between our students and novels.

As teachers and adult readers, we have a tendency to want our students to “get everything” in the novel, so we don’t want to let them read too much without us. When we try to direct a student to discover all of the features of a text during a first reading, Lesser reminds us that we “may require him to read with a strained alertness, which is inimical to enjoyment.” That state of pleasure and relaxation is necessary not only for a student to like a book, but also for a reader to be able to understand the work of fiction. Kelly Gallagher identifies this problem as “overteaching books,” citing it as one of the four causes of “readicide.”

Reading is a personal experience

We also have to understand that our reading of a story is colored by our own imaginations and therefore is different for each reader. Contrasting writers with painters, Gottschall (2012) explains that writers “give us expert line drawings with hints on filling them in. Our minds provide most of the information in the scene, most of the color, shading, and texture. When we read stories, this massive creative effort is going on all the time, chugging away beneath our awareness.” If we push our own interpretations of fiction on our students, we also push our own imaginations on them, which can shut down their imaginative process of reading the novel. If their imaginative process shuts down, they will lose the ability to comprehend the story. Thus, teachers eager to increase comprehension can easily shoot themselves in the foot as they try to help their students “get the story”!

When we allow students to read an entire novel, they can experience it fully and truly themselves, even though this understanding may be limited to their relatively few years on the planet, as compared with our own.

Student Voices on Whole Novels from Whole Novels on Vimeo.

In the classroom, we can build a social experience of living in the literary world without discussing each chapter. The experience becomes intellectual when having read the entire literary work, students can share their varied responses in a community forum and begin to study the ways in which authors are able to use language to provoke certain responses in their readers. We look at the ways in which those responses differ for each reader and what those differences mean.

These critical analysis skills are central in the Common Core State Standards, but teachers are struggling to figure out how to achieve them in ways that engage students at their own developmental level. Whole novel reading provides a way to bring about critical analysis quite naturally. Perhaps ironically, I’ve found that the key to helping students take a work apart for close analysis is letting them first read the whole thing.

Also see a later Ariel Sacks post:

An Author & Her Readers Collaborate Online

And read her commentary about improving comprehension.

Ariel Sacks has been teaching in New York City public schools for nine years. She studied progressive pedagogy at Bank Street College, writes the popular blog On the Shoulders of Giants, is a coauthor of the book Teaching 2030, and plays violin in a Latin Caribbean soul combo.

When I taught ROMEO AND JULIET and JULIUS CAESAR, we listened to, and read along with an entire scene at a time, no interruptions from the teacher at all. I told my students, ‘when you go to the theater and watch a production, there won’t be an English teacher in the first row jumping up to say, “OK, let me explain.” You have to keep listening and watching, keep collecting information.’ Your movie analogy is spot on. Eager to read your book, even though I’ve left the classroom — I’ll be sharing it with my teacher friends..

I agree with encouraging students to read the entire work of art first, and yet, a well written novel has well defined sections, excellent places to pause the reading for an engaging class discussion. While a good analogy, comparing reading to viewing a movie is misleading, for several reasons. Consider attention span, self-regulated motivation, and topic interest, to mention a few. I actually encourage my students to watch the movie first, to engage them in the story line. Then, as we read the novel together, we stop to analyze the use of literary language…

We need to treat reading comprehension as more than just identifying prediction/main ideas/plot summary. While “sequencing” is a skill learned/taught in school, and often tested for in standardized assessments, vocabulary development and inference are just as, if not more, valuable skills to have, for life long learning. The teacher using a novel in her classroom needs to know how to make words come alive, word by word, sentence by sentence, paragraph by paragraph, chapter by chapter…

Treating the novel as a whole is more productive with advanced learners. So, consider age group/ability as well.

Love the idea that “there won’t be an English teacher in the first row jumping up….” You know, though, there WILL probably be at least one English teacher who WANTS to jump up!

@Claudia, I love the application to a play and the theater. Makes so much sense! I’d love to hear your thoughts after reading the book!

@Jeminah, I agree there are always some great places for pausing.

Two ways I deal with this within the whole novels approach:

1. I know that most of these places will come up in the discussion sessions we have at the end of the book, and we reread and are able to discuss them in light of the whole book.

2. Though I like to keep the basic message and framework as, “We read the whole thing first, and then discuss,” but I also do some informal check-ins with the whole class along the way. Sometimes, especially if one of those great places has just come up in our reading schedule, I’ll check-in by saying, “How’s the reading going?” and then “Let’s pick a part from last night’s homework to reread together.” Students often pick a part I might have in mind–other times they pick something I wouldn’t have thought to dwell on, but I learn something new from the experience! This way, we do a bit of rereading and responding along the way, without my prescribing the experience.

@KEM True! Though I really try to stay away from being the “chief thinker” in the classroom–kind of like an adult basketball player playing his hardest against kids on the court– I do acknowledge the fact that I am the most mature reader in the room and sometimes I have some insight to lend to the group, specially when they are circling around an idea for a while on their own and can use a little push. As long as I’m balanced about whose thinking is really driving the work, I occasionally jump up!

I absolutely love this idea and would like to employ it for next school year. As a lover of reading, I am saddened by how many of my students hate reading when they come to me in sixth grade. Does the book have more information about how to organize and manage this technique?

Kimberly, thanks for the question. You can read a review of Whole Novels here at MiddleWeb.

The reviewer describes what’s in the book. We’ve seen the book ourselves – it has lots of the detail that teachers want and need to do it themselves. Sacks also has a supportive website.

Kimberly, I hear you about the pain of seeing students who “hate reading”! And I’m excited to hear that you’d like to try this idea out in your classroom! The book is definitely a practical guide to bringing this method to life in a real classroom with a wide range of learners. I share my methods which I’ve developed with 7th and 8th graders, and I think it’s easily applicable for a sixth grade classroom. Also, there are a bunch of educators at various grade levels sharing how it’s going and asking questions on Twitter using #WholeNovels! (I am @arielacks) That’s an easy way to get quick feedback and responses to questions and it’s fun :) I hope this helps and I hope to hear from you again!

Have you done this with smaller groups reading different novels in order to differentiate by reading ability? I teach 6th grade, but 2/3 of my class read below 4th grade, and I have a few that are reading well above 6th.