Digital Student Portfolios: A Whole-School Approach

Matt Renwick is principal of K-5 Howe Elementary School in Wisconsin Rapids, WI. This article is adapted from the Introduction to his new book Digital Student Portfolios: A Whole School Approach to Connected Learning and Continuous Assessment, available from Powerful Learning Press.

Genesis Cratsenberg has worked as a speech and language teacher in our school for several years. She sees many students throughout the day. This morning, Genesis is meeting with a kindergarten student named David. He struggles to clearly articulate sounds, specifically digraphs (pairs of letters to describe one specific sound).

Genesis starts the lesson by showing David several picture cards. He is instructed to state the name of each image. He does what seems like his best, but often falls short of sounding out each letter and blend. Genesis tells him what he is doing well, and then, being the good teacher she is, kindly points out areas for improvement.

They repeat this activity, in the hope of finding growth. David often glances up at Genesis between interactions, looking to her for the answer to a question that neither of them is seemingly able to solve.

The anatomy of a portfolio entry

At first glance, this would seem like your typical student-teacher interaction. The teacher teaches, the student responds, the teacher assesses, provides feedback and alters instruction, the student responds again, and the process starts over.

This cycle of learning sometime bears fruit. But far too often, it leaves the student and teacher in a perpetual circle of confusion and frustration. Fortunately for David, Genesis is about to pull something else from her instructional toolbox.

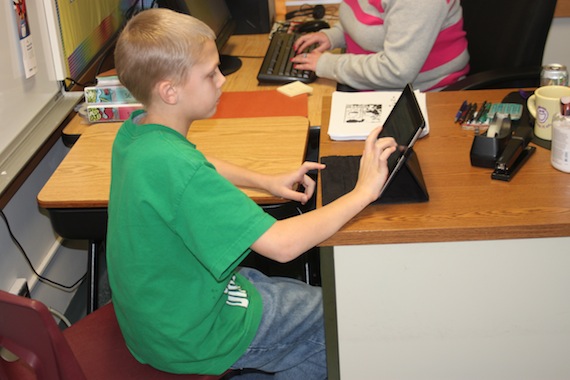

She opens up an app on her iPad that is designed for speech and language teachers. In it, she can record a student’s voice, play back their voice for them, and write down notes – all within the same file. They use the same picture card process as before, except now David knows he is actually going to hear himself speak.

He hesitates for a moment, realizing that this time it’s for real. When he is ready, he again responds to the image that is presented. Genesis stops the recording, plays it back to David, and asks, “Did you say it just like I did?” Instead of frustration, David displays understanding. He has heard himself speak. There is no confusion; he can hear what he needs to improve.

David’s brow furrows, exhibiting a new look of determination as Genesis asks him to try this activity again. This time he slows down his speech, enunciating each sound correctly within the word. Genesis stops the recording and plays it back for him. The smile that comes across David’s face is the feedback Genesis needs to know that he feels successful.

Reflection and follow-through

After the session, Genesis reflects on David’s progress. She writes a few sentences in his notebook within Evernote, a web-based application that can house text, audio, images, and links. She also includes David’s audio, along with any other relevant information. Genesis makes specific comments about his growth in relation to his previous abilities. Much of the feedback is positive in nature. Once ready, she emails this Evernote entry (called a “note”), containing both audio and text, to David’s parents.

A day later, David’s dad stops by to visit Genesis in her office. Before conversation can even start, he states, “I really like that note you emailed us.” Genesis nods and smiles, telling him how happy she is that he found it useful. Dad and Genesis go on to have an in-depth conversation about David’s progress. David’s father and his teacher are partners in advancing his learning. Everyone is focused on the same thing. There is no confusion about David’s progress and current status, where his strengths lie, and where he needs to improve.

Each student in Genesis’ caseload has a series of notes in Evernote. They are organized within an Evernote notebook specifically created for that student. At virtually any time and place, Genesis could pull up any one of her students’ notes to analyze and share. All she would need is a digital device and a connection, either Internet-based or via cellular reception. Thanks to Evernote, the information Genesis has collected from her work with each student is easily organized and quickly accessible whenever and wherever she prepares for future intervention sessions.

The comprehensive collections of work that teachers like Genesis and their students curate and reflect upon on a regular basis are examples of digital student portfolios. Using highly flexible software, they are receptacles for learning from the past, reflections on our current capacities, and goal-setting resources for the future.

Students create meaningful goals

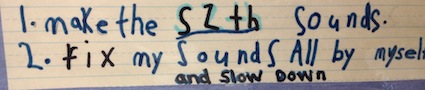

Genesis is not the only person setting the direction for her students’ learning. The students themselves have created personal, meaningful goals for the year. The goals are based on feedback from Genesis, who uses a variety of assessment activities to help the students reflect on their strengths and current reality.

Each student’s learning goals are proudly displayed around her office. The message delivered to everyone who enters her room is, “We are all learners here.” That includes Genesis. As she works with these digital tools and resources, she realizes that her role of teacher has evolved into one of teacher/learner.

She is constantly listening and observing, alert to clues that her students are responding to the instruction she provides. Together, they have agreed upon goals that are high, attainable, and visible every day. And the progress toward these goals is fully documented in each student’s web-based digital portfolio.

This close observation of one teacher’s integration of technology into her daily instruction is an example of where we want to be as a staff. Our K-5 school has engaged in this initiative for the last three years. Our target goal: To enhance and even rethink how we help students make progress toward their learning goals.

Our current portfolio system wasn’t cutting it. To prepare for Portfolio Night in April seemed to suggest that there was little worth sharing between September and March.

While we knew we wanted to bring iPads and Evernote into our classrooms, we did not intend to introduce technology just for the sake of change. Instead, we considered an entry point – ongoing, formative assessment – to begin to bridge the print and digital world.

Pedagogy is still our school’s driver (Fullan, 2014). Technology is treated as an accelerator (Collins, 2001) for change. With this framework in mind, we were able to better manage this shift in how we teach and learn in our school. There were several bumps in the road, but keeping our focus on what was important made the learning process of collecting and organizing student work online more manageable.

Why digital portfolios?

Through digital student portfolios, learners can document current understandings. They can make revisions as their thinking changes and their skill levels grow. Celebrations of their successes can be shared both locally and globally.

The particular software and services used to create these portfolios is a subject of some interest, to be sure, but it is secondary to the “big idea” itself: compiling a dynamic collection of information from many sources, in many forms and with many purposes, all aimed at presenting the most complete story possible of a student’s learning experience.

Different forms of media, such as audio, images, and video, in addition to text, can be inserted into this dynamic compilation of information. Digital student portfolios could be considered a map of a student’s “journey toward excellence” (Routman, 2013). This documentation also serves as description of a school’s own story. We write our own narrative as we work together – students, teachers, and parents – to realize our mission and vision.

Photos: Matt Renwick

Matt Renwick is head principal at Howe Elementary School in Wisconsin Rapids, Wisconsin and author of Digital Student Portfolios. Prior to becoming a principal, Matt served in many other roles as a public educator, including elementary teacher, assistant principal and athletic director. Howe School has earned many accolades for their literacy initiatives and student achievement, including Spotlight School recognition from the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. Connect with Matt via Twitter @readbyexample. He blogs at Reading by Example and writes for EDTECH, MiddleWeb, ASCD and other education resources.

I really like how the student was able to use the recordings to correct the problem practically on his own. The offered immediate feedback allowing the child to take care of it with very little intervention on the part of the instructor. When the students parent came to see the teacher, having used Evernote providedand easily accessible log other student”s progress which in this case turned out to be an illustration of a series of successes. The parent was very pleased. Sounds like everybody wins :-).