5 Reader Activities That Invite Higher Thinking

You’ve taught students to read closely, to annotate, to discuss—now what? How can we get kids to interact with texts in creative ways that require an even higher level of understanding? Here, I’ll share five of my favorite post-reading reader-response activities.

1. Written Reading Responses (RRs)

Doing Reading Responses (RRs) is one of the most effective techniques I know to get kids to formulate new ideas about a fiction or non-fiction text while referring to the text as they do so. It is a logical next step to annotating. This technique can be adapted for middle or high school students.

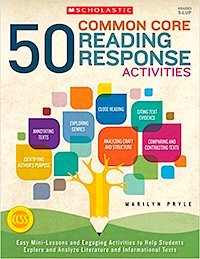

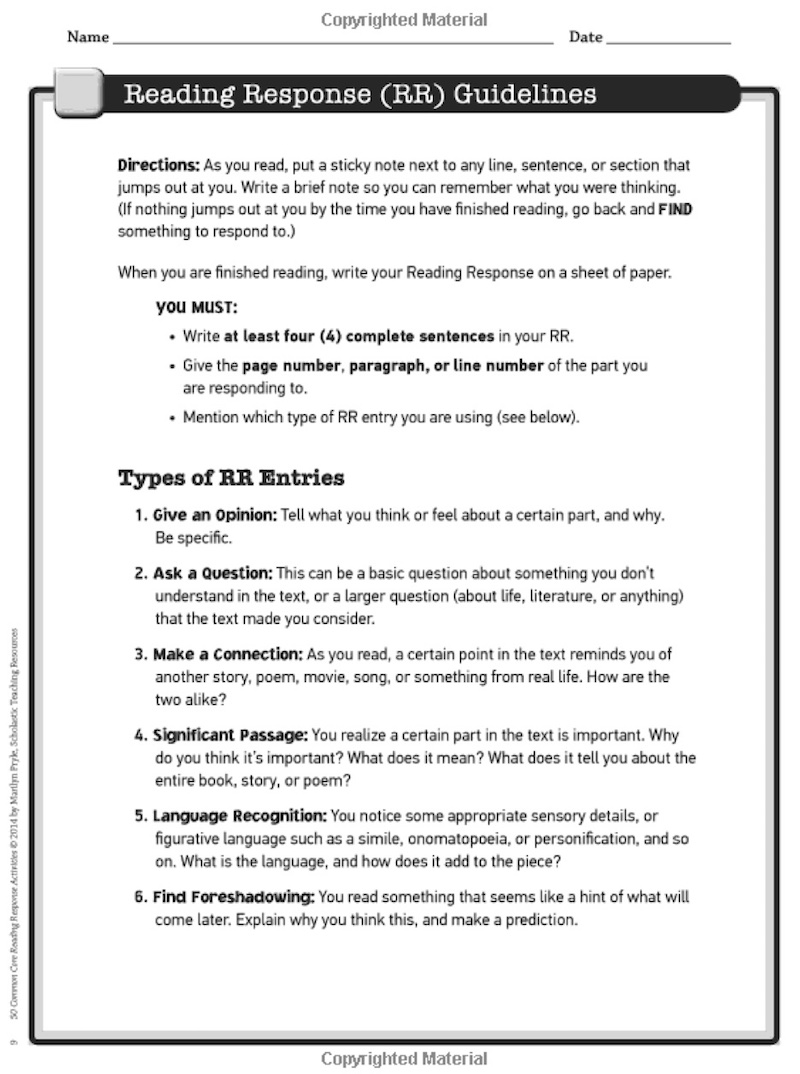

In the beginning of the year, I give students a list of 10-15 RR “types” with descriptions for each. Some of the types include Give an Opinion, Ask a Question, Prove a Character Trait, Dissect a Significant Passage, Make a Connection, Spot the Setting, Find the Figurative Language, Evaluate the Intro, and Mark the Motivation. The rules for writing an RR are as follows:

How To Write an RR

- Label the type of RR you are writing.

- Write at least four sentences.

- Have an original idea; don’t just summarize.

- Quote and cite something in the text to support your idea.

These rules force students to think of an original idea about the text or to elaborate on something they may have briefly annotated. My handout gives them ideas about how to do this. [Editor’s note: Marilyn’s handout is reproduced in her Scholastic book 50 Common Core Reading Response Activities. Used with permission.]

For example, for the Spot the Setting RR, students shouldn’t merely give details about the setting; they should speculate about why the author chose that particular setting, and how it contributes to plot or mood.

The four-sentence rule is required even for questions: I tell students to write a question and then three sentences about what they understand about the question so far. The labeling makes students deliberately acknowledge how they are framing their thoughts about the text.

I usually have students do RRs for homework, and then use their RRs as a springboard and compass for discussion. I often begin class by asking students to share their RRs. As individual students speak up, the rest of us jump to their cited text and follow along. I merely facilitate the conversation, highlighting important points and asking deeper questions when needed. The students themselves will eventually hit upon all the important points of the text; often they will make observations or ask questions I had not thought of myself.

I rarely collect RRs. Instead, after our discussions, I give students another activity to work on, and I circulate to check that the RRs have been done. On days when we haven’t had a whole-group discussion, I might ask each student to summarize his or her RR for me as I walk around. I love this method because it enables me to have a 60-second reading conference with each of them.

Occasionally, though, I will have students complete a “Polished RR,” for which they must choose one of their particularly insightful or interesting RRs, type it up, expand upon it if necessary, and hand it in for a larger grade.

At the end of the first semester, I have students write an RR Analysis Paper in which they examine their reading response habits: Do they always gravitate to one type of RR? Do they have to fight the urge to only summarize? Is there an RR that they have deliberately avoided? What does this say about them as readers and thinkers? This metacognitive exercise helps students see themselves as active participants in their own learning. It also helps refocus and challenge them for the next semester.

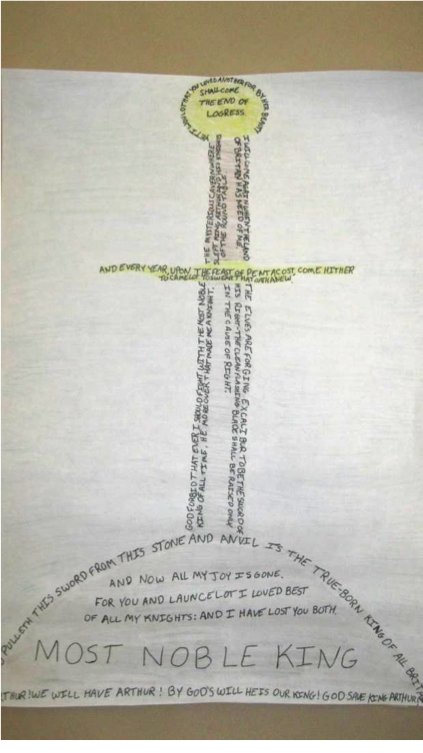

2. Concrete Found Poems

I’m combining two poetic forms here: the “concrete” or shaped poem that middle school students are probably very familiar with, and the “found” poem, which they may not know. Each is a legitimate form in its own right; each can be done with sophistication and deeper meaning. Combining them can push students’ thinking and analysis to a higher level.

To create a concrete found poem, students must only use words, phrases or even whole sentences “found” in their text. Then, they must shape these words into a visual representation on paper. They are not drawing; they must arrange the words, phrases, or sentences into an image on the page.

Students can create concrete found poems about a character, setting, or theme (using a symbol for the concrete structure). They should turn in not only the finished image but also a sheet with the cited words, phrases, or sentences they used to create the image. I require a minimum of ten of these. Below are some examples using the stories of Prometheus and King Arthur:

3. Postcard Home

Most main characters embark on a journey of some kind; this archetypal plot pattern lends itself to a postcard home activity. Have students write in the voice of a journeying character. You could designate a specific recipient or have students choose their own. Here are some questions to get students thinking:

Postcard Brainstorming Questions

Where are you?

Do you like it? Why or why not?

What has happened to you so far? (one or two sentences)

What are you struggling with?

What have you learned so far, about yourself or others?

What will you do?

How do you feel about the recipient?

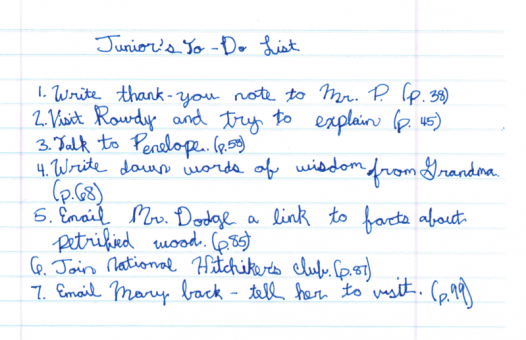

4. Character To-Do List

We all have many things we want to accomplish in the near and far future, and characters are no different! Tell students to choose a character from the text—or you can assign characters so all the characters are represented. Challenge them to get inside that character’s head to create a to-do list. They can think about the following questions:

Character To-Do List Brainstorming Questions

What does he or she have to do on a daily basis?

What does the character want to do or achieve?

What are the character’s responsibilities?

What are the character’s goals?

Where does the character have to go?

Whom does the character need to speak to?

Students should use actual information from the text, of course, but urge them to also infer information and supply text evidence to support their inferences. It helps to set a minimum number of tasks, such as ten. You can suggest that if a character has a large goal on the list, that goal can be broken down into smaller tasks. For example, if a character’s goal is to “win karate tournament,” smaller steps might include, “Practice 2 hours a day” and “Watch opponents compete.” This activity will measure students’ comprehension, their understanding of a character’s underlying motives, their ability to draw inferences from existing information, and their ability to predict a character’s future actions.

For an extra challenge, have students cite the pages containing information from which they drew inferences. Below is an example using Sherman Alexie’s The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian.

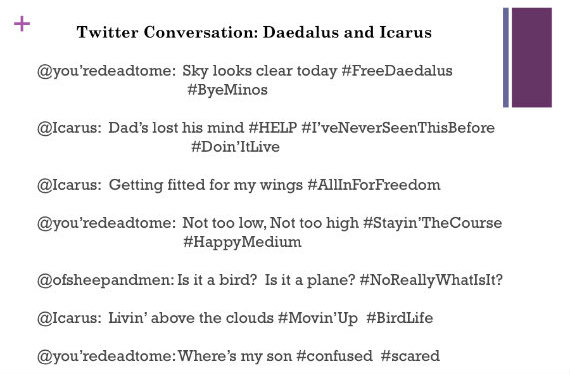

5. Write a Twitter Conversation

5. Write a Twitter Conversation

Students love this! Have them work with partners to rewrite part of the text as a Twitter conversation among the characters. They do not have to actually use Twitter; they can just write out the conversation on paper, perhaps using Twitter’s 140-character maximum length. This is not merely a summarizing activity—deeper understandings can surface with this exercise.

For example, students’ choices of Twitter handles for each character may reveal character traits; their use of hashtags could express inferences about personalities and themes. I am always amazed at the humor and wit of the students when we do this activity, and the students themselves are often gasping with laughter by the end of it.

Below is a Twitter conversation between Daedalus, Icarus, and the shepherd that saw them flying.

Keeping It Real

Applying real-word literacy practices, like Twitter chats and To-Do Lists, to in-class texts engages students and deepens understanding. For more ideas, or to view full assignment sheets and rubric possibilities for the assignments suggested here, please see my book, 50 Common Core Reading Response Activities (Scholastic, 2014). [Read MiddleWeb’s review.]

If you’d like to explore the topic of this post in more depth, Marilyn’s most recent book is Reading with Presence: Crafting Meaningful, Evidenced-Based Reading Responses (Heinemann, 2018). She can be reached at http://marilynpryle.com/.

Great list, thanks for sharing!

Can’t wait to try the concrete found poems for reading science texts. A great way for students to build conceptual ideas about what they are learning. Thanks!

Very good content, we will do this on our own blog site. Many thanks for sharing.