Which History Approach Works Best for Kids?

A MiddleWeb Blog

Two years ago I developed a unit on federalism with a colleague from another school who was working on his doctorate in education. When he asked me to think of concepts that are particularly difficult and important to teach, the tension between state and federal governments topped my list.

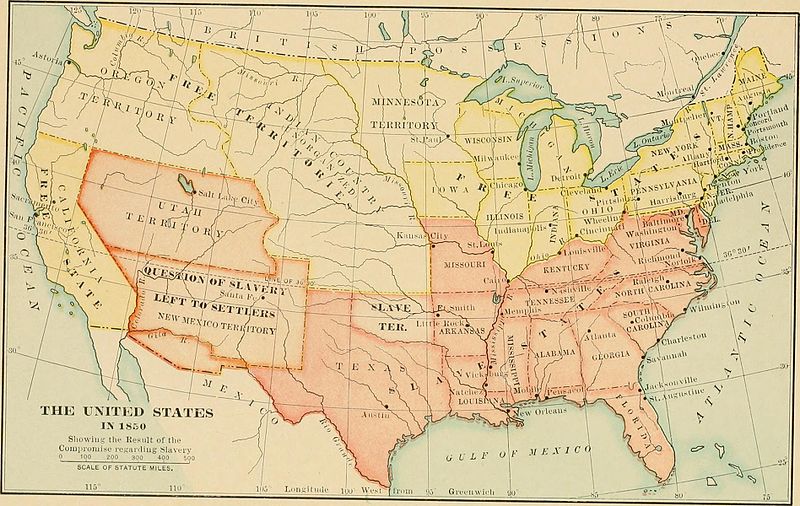

In this three-week unit, the eighth graders and I discuss the problems with the Articles of Confederation in the 1780s, jump to the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850, dash through the 1850s with a brief stop at Lincoln’s “House Divided” speech, mention Fort Sumter in 1861, and then catapult 100 years into the future, to Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School in 1957.

Throughout, I bring in current events relating to federalism, such as Ohio’s recent decision rejecting legal marijuana, Houston’s vote against an anti-discrimination statute, and a Mississippi man throwing a bomb into a Walmart because the store had stopped selling Confederate flags.

The pros and cons of time hopping

There are so many things I love about these three weeks:

- The framework of federalism across time demands complex thinking.

- Students read the newspaper with a new lens and realize that the creative tension between the national and state governments is everywhere.

- I have to stay current. Last year’s enormous federalism issue was gay marriage; now that’s literally history. This year recreational marijuana, gun control and abortion laws are playing large on the national screen.

- Students realize and appreciate the idea that conflict is “hardwired” into the American political system – that we are supposed to take risks and experiment, as individuals and as states.

And yet… and yet…

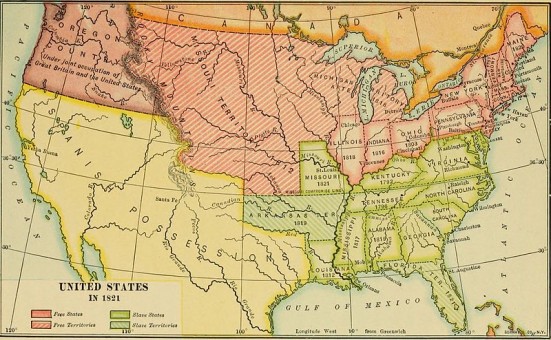

This morning, as we looked at a map of the Missouri Compromise, Arek asked, “What happened if a slave ran away across the Ohio River from Kentucky into Ohio?”

“Yes!” I said, throwing my arms to the sides, thrilled by how perfect his question was to open a discussion. “That’s called the Fugitive Slave Act, and you’ll be reading about it tonight with the Compromise of 1850. Actually, this was the second such law – the first one was passed in 1793, a few years after the Constitution was signed.”

At which point the self-doubt started.

How can students possibly understand the magnitude of slavery and the Fugitive Slave Act if we haven’t yet read the Constitution?

How can I possibly be teaching the 1850s tomorrow if they don’t know about the Mexican-American War?

When can I fit in an excerpt from Uncle Tom’s Cabin to make them feel what it was like to cross the Ohio River in 1852?

And, most disturbing, I wonder: Am I bowdlerizing the narrative of history by cherry-picking the highlights?

Which approach will mean more to students?

What makes these questions more difficult to answer is that today’s thematic class felt rich.

We read Thomas Jefferson’s magnificent “wolf by the ear” letter about the compromise, writing out main ideas and then drawing thumbnail sketches of two favorite images, such as “a fire bell in the night” or “justice…in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.”

But – and this is a big but – which approach will inspire students to apply more history to their lives? Which approach will inspire them to read more about the time period: focusing on one topic per class to give a deep and narrowing understanding, or covering many details during class to show the depth of government policy and human biography?

Ultimately I come back to the idea of what students will remember in one, five or ten years. If we spend most of a period on the Missouri Compromise, the self-doubt and fallibility of the decision makers will likely sink in more than if we simply read a textbook and discussed the 36’30” line for a few minutes.

But today, for whatever reason, I’m yearning for some old-fashioned history. History that builds up in our minds, layer by layer, as it did when it happened.

If you’re a history teacher, would you describe yourself as more chronological or thematic? Do you feel this tug-of-war in your teaching?

To me, a retired teacher and administrator, your class sounds wonderful! Keep doing what you’re doing, and remember that even educators have gaps in their education and what you want is to create life-long learners who love history. It sounds like you’re doing that.

Mary, thank you for your encouragement. I love the idea of creating life-long learners, and I hope you’re enjoying your retirement.

I have this exact same dilemma at least 5 times per day. Seriously. It is a great thing to think about. I keep coming back to the fact that as history teachers it is our job to teach skills that will help our students in their future. Think of it this way. Tony Wagner in his book Global Achievement Gap, writes about the seven survival skills.

1. Problem-solving and critical thinking; Open ended questions, essential questions, big ideas…

2. Collaboration across networks and leading by influence; Wikis, SharePoint, cooperative learning, discussions, community member speakers…

3. Agility and adaptability; Debates, presentations, open source software…

4. Initiative and entrepreneurship; Teams, project based learning…

5. Effective written and oral communication; Reporting, newspapers, tweets, blogging, web sites…

6. Accessing and analyzing information; Using search engines, learning search modifiers, library research…

7. Curiosity and imagination. Make school fun…

These things can all be done chronologically BUT… I think teaching your kids to think about how history is not really history. It is still happening and it is a long process. Race relations are still tense. Religious freedoms and persecution happened in the 1600s when America was colonies and now we do the same to other religions. Elections are still contentious like they have alway been. Politics are still nasty and have always been. Propaganda is part of our world and it has been for a long time.

Our job is to teach kids the ability to think and learn and improve upon the skills they need for future success, how we do that best fits them being done in a thematic way connecting time periods as much as possible.

Eric, I really enjoyed reading your list of skills, and I agree that thematic history can definitely approach every item on the list – maybe especially #7! It sounds as if your own classes are lively and fun.

The “talking about teaching” book group at my school is reading Tony Wagner’s “Most Likely to Succeed: Preparing Our Kids for the Innovation Era” for our next meeting, and I’m looking forward to thinking about innovation in relation to history teaching.

Sarah,

First, this is a great post – one that I’m sure has many fellow history teachers pondering this very notion/dilemma of teaching our discipline straight chronologically, or through themes. As a “recovering traditional” history teacher, I found myself constantly working hard to plan authentic and engaging ways to teach my curriculum(s) – much of which was successful but I felt did not fully engage the 21st century learner. That’s when I decided I wanted to start each unit with a more engaging “hook” – usually a current event or something contemporary for my students. Since then (nearly 3 years ago) I haven’t looked back and have continued to link “history” to current events through themes and patterns.

For example, I am just finishing up a unit called “Race and Civil Rights in America” (I teach 8th Grade US History at an Independent all-boys school in Massachusetts). We lead with a revisitation of Slavery, followed up by the Reconstruction period. By doing so, my students have a strong foundation (content wise) for WHY humans were commodified by other humans. Moreover, my students are better able to trace the origins of racial tensions that have sparked some more recent, heated debates such as the #BlackLivesMatter vs. #AllLivesMatter saga. The students also look at many of the strategies of Civil Rights advocates and explore whose strategy was the most realistic in the context of time they lived in versus today. This unit closes with a study of life under Jim Crow rule and a viewing of “The Freedom Riders” documentary which, again, is brought into context by discussing the role of students not much older than them leading the charge for social change.

Are there gaps and periods of history that I cannot fit-into my 9-month curricula because of this thematic approach? Absolutely. However, working at an Independent school allows flexibility and freedom to create a curriculum centered around what’s in the best interest of the students. Likewise, being a big proponent of Project-Based Learning and student-centered learning, I always revert back to the “6 C’s of Project-Based Learning”: Collaboration, Cultural Competencies; Communication; Critical Thinking; Creativity; and Character” as the way in which I can assess my own teaching practice. It allows students to actively explore history in relation to their own lives today, and help them achieve (or at least strive to) understanding of these 21st century skills mapped out above. To me, these skills are more important than rote memorization of facts.

Keep up the good work!

Love your thinking Brad. This is right along how I think and hope to continue growing toward. Can I contact you and pick your brain some more??

Absolutely, Mr. Kipling (I assume you do have a first name, too?!). Please shoot me an email: bbelin@fessenden.org

Brad, what a wonderful unit you describe. Using current issues to launch discussion sounds very rich. Your description of yourself as a “recovering traditional” history teacher made me smile, and it does seem that you and Eric overlap a lot in your approaches. Thanks for the inspiring words.

Hi Sarah,

I love the fact that you’re willing to grapple openly and thoughtfully with this issue. Many educators territorially cling to one end of the spectrum. It’s an easy way to approach things, but seems to lack the depth and nuance you consider so well.

I’ve taught for 40 years and have been fortunate to hold a few positions where I could go around the country to examine pedagogical techniques – “highlight best practices” in the parlance of maybe a decade ago. For my money, what you’re doing now shows the nobility in the education profession. We keep trying to improve so that we can help our kids to improve.

I teach MS history. Our eighth grade course runs from 1865 – present. We hit things chronologically, except that during our study of each issue we look at the way that issue shows up today. We’re looking at immigration in the late 1800s – early 1900s. Are you kidding? How much more topical could this be? We look at the European refugee crisis, Mexican immigration, etc., and several kids call or write state or national congresspeople.

We just finished with 19th-century imperialism. Today? Is Putin acting as an imperialist in Ukraine? The west in Iraq? Afghanistan? Kids come down heavily on both sides here. Write to Putin and ask him. Some have.

Plessy v Ferguson, DuBois, Washington? Affirmative action. Bakke decision. Ferguson. Eric Garner. Laguna McDonald. But British policewoman diffusing violent situation with dance-off. Many articles about police saving people. Providing protection to communities vs. institutional misuse of power.

I’d suggest that you can teach chronologically, yet promote thematic thinking.

Keep wrestling with the big issues, Sarah. Simply by being willing to do this, you’re modeling the intellectual investment you want from your kids.

Cheers,

Mark

Mark,

Your course sounds so exciting. It also seems that you promote activism in our current world by studying issues of the past. Writing to Putin is a fantastic idea! (This year my students are fascinated by both him and Donald Trump.)

Speaking of the immigration issue, I’ve loved the lyrics in the new musical “Hamilton” (http://www.middleweb.com/26340/hamilton-on-broadway-student-tickets-available/) that speak to the power of immigrants to reshape a country.

Thank you for your encouraging words about the power of intellectual modeling, too.

All the best,

Sarah

Love to hear the feedback and your approaches. I teach U.S. history at the 6th grade level at a private, progressive school and begin with colonization and go chronologically through time. I know we cannot “cover” all the topics I would like to , but as one educator told me recently, focusing on what we can help the students “uncover” is important. I combine group and individual research skills as we use projects to focus on historical periods, but also put them in perspective with more current matters. We did a nice unit on the Salem Witch Trials, which brought up the broader issue of witch hunts, incorporating McCarthyism, post 9/11 events, etc. I love how the students grasp onto the historical events, and recognize that history not only repeats itself, but is all around us, whether good or bad. We also accentuate public speaking skills and utilize debates quite often to recognize the events as historically important, but also as a way to get our 6th graders to think deeply, extemporaneously, and with sophistication. I have only been teaching 6 years after a prior career, and I find this segment of my life fascinating.

Gary, I am going to start using the term “uncover”! Your unit on the Salem Witch Trials sounds relevant historically and currently. Glad to hear you are enjoying teaching so much, too.

When I was a junior in high school (lo these many years ago), I was subjected to an experimental approach to American history. The subject matter was divided into four thematic quarters: political history, economic history, social history, and a fourth that I haven’t remembered for years. Four history teachers each took one topic, and the students cycled through each teacher’s classroom through the year. My impression was that we learned a lot more about the latter three subjects than we had in earlier history classes. Most history was taught from a political slant in other years.

This was in a West Texas school district in the late sixties. For reference, I was a top-1%-of-the-class student and later earned a degree from Rice University including a Texas teaching certificate, so my experience may not have been typical. But I felt I learned a much broader understanding of American history.

Kathleen, the program must have been powerful if it has stayed in your mind over the years. Thanks for sharing an approach that sounds as if it could still work today!

My guess is that either way your students are lucky to have you. Your post makes me wonder about the role assessment plays in this too. It would seem that regardless of teaching chronologically or thematically you would want your students to demonstrate their knowledge of themes…and to do so in a manner which demonstrates critical thinking and the ability to connect the past with the present…and even the future.

With that, I wonder about the potential of asking students to role play and debate both historical and contemporary issues. I wonder about how you might ask them to consider historical themes, such as common causes of past political revolutions for instance, and then how you might ask them to make an argument of where/when we could expect to see that theme again.

What if you came in character as the Director of the CIA, handed each of your analysts (students) a top secret envelope with a memo about the urgent need to identify the next country most likely to see political upheaval? The necessity of the assignment is to “ensure the safety of our field agents and citizens abroad.” Then using a list of historical criteria established collectively (formative assessment) by you and the department (class)…individual students or teams could research and then present the facts and arguments for the country they feel most likely to experience upheaval.

Of course, all of this would need to be done in character!

@finleyjd

This is a fantastic idea for predicting hot spots and truly understanding themes. Are you teaching middle school history now? If so, and you try something like this, I’d love to hear how it goes. It sounds like an ideal example of performance-based assessment.

I appreciated ready this post. I have been on the thematic side of the argument and worry about students’ lack of chronology. I did conduct a study that compared the two methods and was happy with the results. I started using the thematic method mainly due to a lack of resources that required a multi-source approach. After that I was sold, and believe the benefits of teaching historical thinking through a thematic lens outweigh the negatives.

Thanks for the interesting post.

Andrew, your study sounds really interesting. A thematic approach definitely benefits from a variety of sources. Thanks for the feedback!