How to Create Culturally Responsive Classrooms

A MiddleWeb Blog

Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT) is a current buzzword in education. And you know what? As an ambassador for English Language Learners, I’m going to capitalize on this momentum.

Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT) is a current buzzword in education. And you know what? As an ambassador for English Language Learners, I’m going to capitalize on this momentum.

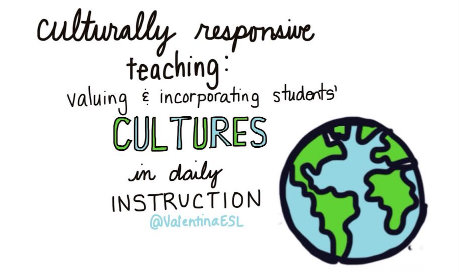

First, let’s make sure we have a common understanding of the term. There’s nothing more frustrating than someone saying, “let’s be more culturally responsive” or “teach with more rigor” but not really defining what that means.

There are many definitions for CRT. To sum them up, CRT is teaching that takes the experiences and assets of the students and uses them to enrich the curriculum. Rather than taking the curriculum and trying to fit it into the students’ lives, CRT reverses this mindset.

Culturally Responsive Teaching

What it is…

♦ assets based

♦ student centered

♦ values native languages, cultures, and experiences of students

♦ challenges and supports students

What it is not…

♦ strategies

♦ curriculum

♦ only for some students

♦ watered down lessons

When we take a culturally responsive stance in our classrooms, students will respond by having a lower affective filter. Their walls of fear and anxiety will come down. When students feel safe and comfortable to learn, they will be capable of learning more in their content classrooms. Their cognitive and linguistic development will progress at a faster rate.

A classroom or campus that is culturally responsive believes that the students who learn in their building enrich the building with their cultures and backgrounds. These teachers want students to share their cultures, traditions, and languages with the class. Students feel safe and secure, self-confident and proud of their individuality. Instead of feeling they have to shed their native language, culture, and traditions, students feel empowered by their uniqueness.

CRT embraces differences and creates an environment where all learners are valued. CRT is not about eating tacos once a year to celebrate Cinco de Mayo. It is everyday practices that embrace the cultures of all students no matter where they come from, what language they speak, or what color their skin may be.

How does this happen?

1. In order to be assets based, the teacher must get to know the students beyond the permanent record folder.

ELLs and students who struggle benefit from feeling that they come with useful knowledge. If a student knows a lot about families who make a living from the sea, we can use that to help them progress. Knowing students’ likes/dislikes, hobbies, and family life to help make connections with learning proves beneficial.

2. Keeping students at the center of learning is key to success.

Remember that we teach students the curriculum and not vice versa. Cooperative learning, project based learning (PBL), and student choice will help students develop and accelerate reading, writing, listening, and speaking skills. With PBL, we can take our students’ assets (what the students know well) and use them to help drive learning.

For example, if a student has a curiosity for rain forests and would like to research them because there were many in his native country, this may be a good topic for him. When students have choice in learning, an environment is created where students feel that their learning is valued. In addition, placing student work on the classroom walls and including signs in other languages helps to build an inclusive, accepting community.

3. Valuing a student’s native language gives them power and a sense of assurance that it’s okay to speak a language other than English.

Feeling that you have to shed your native culture and language is one of the worst feelings ever. Letting our students know that what they have is something special and unique is important. They need to hear it from their teachers. We are influential role models in their lives and when we verbalize this to them, it means something.

We can value their native language by learning a few key words and using them in the class. Words like hello, how are you, bye, seasons, days of the week, etc. Encouraging students to speak in their native language helps build empathy and models for English-only students that we value and accept other languages.

As with encouraging ELLs to speak their native language, reading their languages builds their self-esteem and confidence as a bilingual student. And for our monolingual students, it sends a message that we embrace and invite other cultures into our classrooms and lives.

4. We have to remember that not knowing English (yet) is not an indicator of intelligence level.

For instance, I don’t know Korean (yet – maybe one day I’ll decide to learn it), but I would not want my intelligence judged on how much Korean I can read, speak, write, or listen to.

That being said, if I did go to Korea as a grade school student, I would want to learn grade level curriculum. I certainly wouldn’t want my teacher to give me coloring sheets. ELLs are entitled to equal access to grade level curriculum using scaffolds and accommodations to support their current linguistic needs.

It is up to us as educators to learn more about how to effectively instruct ELLs. If we are not meeting their needs, it is not something they are doing wrong. We have to look at our practices and reflect.

Unfortunately, pre-service teachers receive very little training on serving ELLs, and much of the learning happens hands-on when we get our first classrooms. It’s up to us and the districts where we work to ensure that we continue to develop the skills required to meet the diverse needs of our changing population.

Our ELLs need us to set high expectations for them. They are expecting us to expect much of them. We have to remember that they are just as capable of achieving as all of our monolingual students. ELLs may be carrying a heavier workload because they are learning English along with learning a new culture and new content, but they have dreams and hopes like every child. We must set high goals for them as well.

Creating opportunities for each of our students to shine

The bottom line is always the same — the student comes first.

I LOVE this post! Your straightforward advice is refreshing. I have long been critical of edu-speak that isn’t defined well. Thanks for the great read!

Thank you, Rita! I agree! It’s so important that we’re all on the same page when we talk about classroom expectations.

Hi, Valentina! Congrats on the launchof your new blog! You are unstoppable!

This article is great! Teachers in our field of education first must help students feel thatthey are ina safe place, where they are cared for, and where they are protected. Once they believe and trust us, they will then be more willing to take linguistic risks.

These four suggestions are great! Keep the posts coming!

Tan, you are such an inspiration to all teachers including me! Thanks for reading my new blog, cheering me on, and sharing it with others!

Thanks for this explanation of CRT and the specific examples of what teachers can do. I’ve heard of CRT before but wasn’t sure how to implement. So thank you, great job!

Hi Carol! Thanks for the feedback. I truly appreciate it. Have a wonderful year with your students!

I will share this with my pre-service teachers. They are currently writing a culturally relevant lesson in math, and I suggested that they pair it with another assignment they have – writing a journal about a community walk or an interview with a student. I suggested that getting to know a student would help them to write a culturally relevant lesson.

Thank you for sharing, Shelly! I agree. Getting to know their students will help them write culturally relevant and responsive lessons.

Great Article! Thanks!

In this article, This #4 really hit some reality in our district. Some teachers still need to understand ELL students in a different culture. In our district our students are 90% Navajo students. Not from a different country but a different culture. This statement is exact the reason for CRT:

“4. We have to remember that not knowing English (yet) is not an indicator of intelligence level.”

This next statement also clarifies CRT need.

“For instance, I don’t know Korean (yet – maybe one day I’ll decide to learn it), but I would not want my intelligence judged on how much Korean I can read, speak, write, or listen to.

That being said, if I did go to Korea as a grade school student, I would want to learn grade level curriculum. I certainly wouldn’t want my teacher to give me coloring sheets. ”

Some teachers need to understand the right for ELL to received general curriculum with accommodations (repetitive instruction, visual aids, more time, etc.) and not label ELL as:

“Or label me SPED.”

If I were a student or parent I would not accept “just coloring papers or word searches, etc.” Would You accept this?