Refugees: Using Comics to Foster Understanding

A MiddleWeb Blog

In class discussions, I had been trying to balance the difficulties governments encounter when accepting refugees with the conditions that force people to leave their homes.

To understand what displaced people face, we had:

- Read an account of the Jews sent back to Europe in 1939 on the USS St. Louis, from the excellent U.S. history reader Reasoning with Democratic Values 2.0.

- Looked at a CNN video of a refugee camp in Northern Syria and a US Department of State photo of the Za’atri Refugee Camp in Jordan.

- Heard Samantha Power, former U.S. ambassador to the U.N., provide her definition of a refugee for Facing History and Ourselves.

- Created a chart on refugees versus migrants, based on information provided by the UN Refugee Agency.

- Listened to Warsan Shire’s poem “Home”. Earlier in the year, it served a model for a spoken word poem on current events. Now it reminded us of the people who “only leave home/ when home won’t let you stay.”

We were saturated in voices, stories and images that aroused empathy.

Even so, I decided to show one more source, to give one more first-hand perspective, before a debate on the impact of total war on civilians.

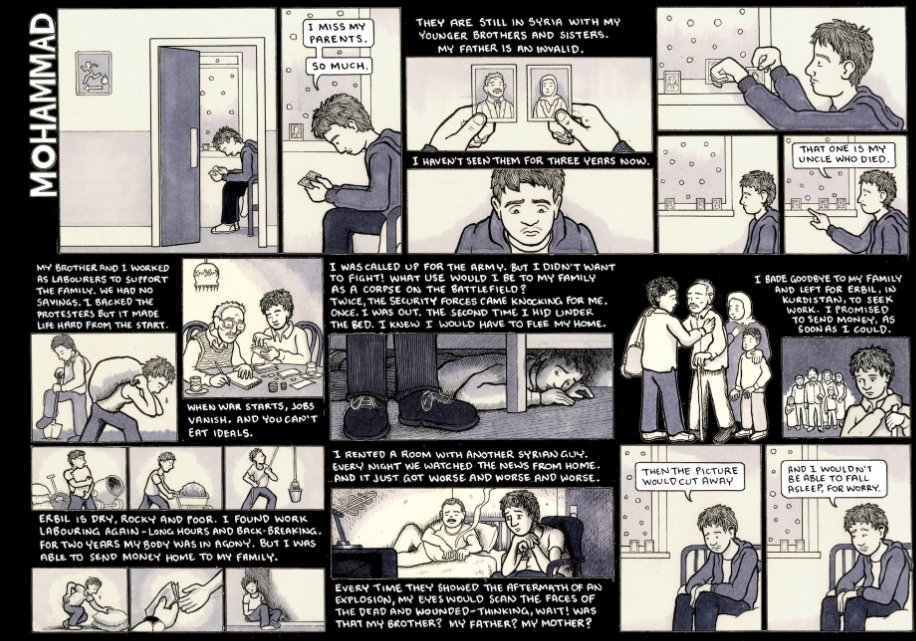

It was a comic strip, from Brown University’s excellent Choices Program. A colleague who recently studied the refugee crisis in Bulgaria, through a Fulbright-Hayes scholarship, had recommended it. Among other immigrant stories, the page told the story of Mohammad, a refugee from Syria who traveled through Europe, hoping to find sanctuary in Norway.

That day in class, I projected the comic strip onscreen. In our darkened room, I read the entire four pages aloud. (This PDF has both the comic and teacher/student resources – images of war may call for teacher discretion.)

By the time I had finished reading – including lines such as “You can’t eat ideals” and “I had driven my family to debt”– the eighth graders were uncharacteristically silent.

Afterward, when I asked students to reflect on how the strip had affected them, they wrote:

-

-

- “It was really sad to see how desperate the refugees were to escape from their original, war-torn countries, & on their long & hard journey, they still have to earn money and help their families.” (Trinity)

- “I think that Mohammad should just stay [in Norway] until he finds a way to pay his debt. It was a powerful way to tell the story.” (Destiny)

- “All he cared about was supporting his family.” (Isabel)

- “The story felt very real and true of what refugees have to deal with. It almost made me angry that he wasn’t accepted to Norway, and his story made me forget about the cons of accepting refugees or accepting too many refugees.” (Alec)

-

Alec nailed it. The comic strip put us into the head of Mohammad so thoroughly that the refugee crisis felt real and individual, not remote and vast.

Why Are Comic Strips So Powerful?

After class, I wondered why I had not predicted the intensity of the students’ reaction.

And last year I loved reading Debbie Tung’s Quiet Girl in a Noisy World: An Introvert’s Story, a thematic complement to Susan Cain’s book Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking.

What I remembered that day in our class is that, while photos and texts can bring alive an issue one medium at a time, comics have the power to drop us into a real situation both visually and verbally. As one student said of Mohammad, “You can’t get out of his head.”

With such immediacy comes intensity. The comics on the Choices site – Syrian Refugees: Understanding Stories with Comics – don’t flinch at portraying death and despair. I would definitely recommend reading through them to decide which might be appropriate for certain groups of students.

What Happened to Mohammad?

After I read aloud the coda to Mohammad’s story – “Mohammad is still anxiously waiting for a decision to be made under the Dublin agreement if he will be returned to Hungary” – a number of kids in each class asked, “So what happened to him?”

The site didn’t say.

I emailed the Choices Program, which directed me to the comic’s original creator, Why Comics? It’s a London-based group that “exists to educate, inspire, and engage young people on contemporary humanitarian and social issues to promote equality and diversity through innovative educational resources.” (If you’re interested, you can download their 13-page Teacher Guidance PDF.)

A representative from the site emailed me back: “Mohammad’s comic story was produced some time ago now, so our founder has reached out to Norwegian People’s Aid (the association that facilitated our interviews with the participants) to know how Mohammad is. We’ll let you know as soon as they get in touch.”

School finished. I forgot about the email exchange. But then, a couple of weeks later, I heard back from the organization again: “I’m happy to share very good news with you – I nudged some people in Norway and I was able to find out that Mohammad has been granted permanent stay in the country.”

This sounds like a happy ending, worthy of a new comic strip.

Want more? For a plethora of graphic novels that teach history, check out this excellent list from YALSA, the Young Adult Library Services Association. The New York Times Learning Network also offers a page with dozens of ideas for using comics in education: From Superheroes to Syrian Refugees: Teaching Comics and Graphic Novels With Resources From the New York Times.

__________________________________________________

This is a wonderful article. Thank you.