Help Students Start Asking Questions Again!

A MiddleWeb Blog

One of the toughest – and most worthwhile – classroom teaching tasks is working with students to develop their capacity and confidence to ask good questions.

As soon as they are old enough to talk, kids want to know everything about the world around them. Where does wind come from? How do birds not get tired? Why do we have armpits? Each inquiry is a reflection of their inexperience and natural inclination to seek out information, explanation, and clarification about their environment (Isaacs, 2018).

Unfortunately, the older students get, the fewer questions they ask. Some stop asking them all together. The questions our tweens and teens do offer up are mostly procedural…mere attempts to find out information about an assignment.

This happens for a number of reasons, including heightened self-awareness, fear of ridicule from their peers, and classrooms that are often overflowing with teacher talk but suffering a drought when it comes to questions posed by students.

Three Questions for Every Teacher

As educators, we understand the value in promoting student participation. Practice in formulating questions is part of that process. When learners devise their own questions, they are obliged to think about the material, analyze it based on what they already know, evaluate information using evidence, and determine what they have yet to learn (Soiferman, 2019).

That’s just what we dream will always be happening in our classrooms.

For teachers desiring a classroom rich in inquiry and student-created questions, consider asking three How’s as you design each learning activity:

1. Valuing Student Questions

Teachers should start by asking themselves, How do I communicate to students that I value their questions? Most of us establish (and even post) classroom expectations and norms dealing with peer interaction, procedures, and behavior. It’s equally important to establish an expectation for engaged learning by formulating and seeking answers to questions.

Consider including at least one one norm or ‘awareness’ statement such as…

- We learn through questions.

- We are question askers.

- Asking questions is a sign of active, powerful thinking.

- Questions are valued in this classroom.

- Questions are asked by and of all learners, including the teacher!

Much of our communication occurs “in the moment” through verbal cues such as…

- I really appreciate the questions that have been asked so far.

- That is a really interesting question.

- I can tell we are really thinking about this.

- Let’s hear from someone we haven’t heard from yet.

- I feel like I have done a lot of talking. What questions do you have?

- What would you like to discuss or find out more about?

- What questions do you have that haven’t been addressed yet?

A teacher’s nonverbal communication is equally important (Stern, 2019) when we are encouraging student inquiry and thinking. This includes making eye contact, nodding as students share thoughts and questions, and moving away from the front of the room during student discussion to communicate the need for students to take a more central role in classroom communication.

Another way to communicate to students the value of questioning could be to have students work in teams to define and discuss the difference between being ready, willing, and able to ask questions in class.

Regardless of the approach we take, the intent should be to help students seek explanations and alternatives more frequently, take an increasingly active role in their own learning, think deeply about what they are trying to achieve, express themselves more easily, and use self-assessment to monitor and evaluate their own understanding (Moss & Brookhart, 2019).

2. Time and Space for Student Thought

It’s not enough for teachers to simply acknowledge the importance of students’ questions in the classroom (Mueller, 2016). We must also work to make student inquiry an integral part of every lesson by asking ourselves… How will I ensure that students have sufficient time and space to formulate questions?

How much do you talk? Videoing a lesson or having a colleague sit in makes it possible to chart student vs. teacher questions, to observe which students are responding, and catalogue the types of queries students make.

It’s also crucial for both teachers and students to remember that there is no single, perfect question for us to come up with. Instead, we should make a conscious and concerted effort to work before, during, and after a lesson to develop skills like critical thinking, building on (and making connections to) background knowledge, and practicing metacognition.

Despite our good intentions, students are rarely afforded enough time to process information, make connections, formulate questions, and respond to each other’s ideas (Hattie, 2012).

When I asked an exceptional veteran teacher how much wait-time learners need, she wisely answered, “More than you think they need and more than you feel comfortable giving.”

Tools To Help Students Craft Good Questions

Technology can be an effective and powerful means of encouraging students to formulate, collect, and share student questions.

- GoSoapBox allows students to anonymously contribute questions and opinions without worrying about the reactions of their peers. The teacher, however, is able to see who says what in order to identify misconceptions, gain insight into student learning, and prevent any inappropriate use. (There’s even a “confusion barometer.”)

Students can view or vote on questions while teachers can mark them as answered as they are discussed in class. The tool is free for small classes (fewer than 30 students), and can be upgraded for larger class sizes for a small fee.

- Google Forms can be a wonderful tool for students to submit questions during or after class. Click here to view a sample template for teachers or here to make a copy of it.

- For teachers using Google Classroom, the question tool can also be used to ask students to formulate and submit questions and queries that they have. A quick tutorial on how to get started can be found here.

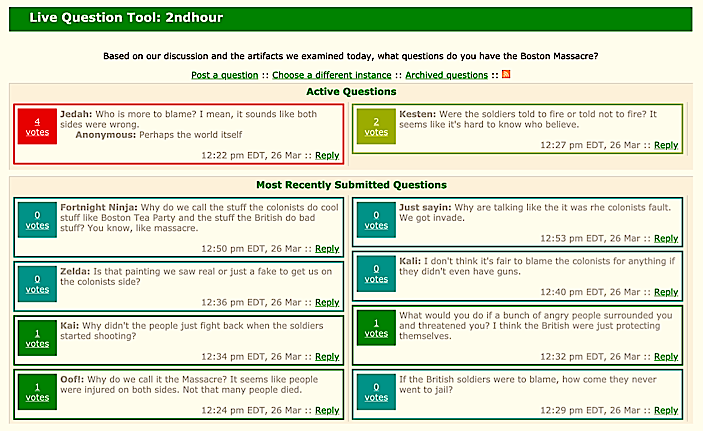

- In a previous post, I shared the Live Question Tool that allows students to pose questions electronically and then vote on which ones are the most important or relevant based on the lesson. Here’s an example I’ll reshare from a friend who’s a history teacher.

3. Use Models and Menus as Scaffolds

Explicit modeling and practice are fundamental for students working to formulate worthwhile questions. That’s why I always like to ask myself… How can I scaffold and support student questioning and move them toward greater autonomy?

Whether provided by the teacher or more experienced peers, modeling allows students to observe the thought processes that experienced “question creators” go through and then try out some thinking techniques likely to result in success.

For example, in a recent post for TeachThought, Terry Heick shared 75 questions that students can ask themselves before, during, and after new information is presented. In addition, Jackie Walsh shared suggestions on MiddleWeb for How to Get Your Students to Ask More Questions with examples and stems for various types of questions to kick off the process.

Lively Forums of Learning

The task of a teacher is to create opportunities for others to become independent thinkers and self-directed learners. We get our students off to a good start by providing models of constructive thought and menus of sample questions. Over time, however, as our kiddos practice, develop patience, and improve their own capacity to deepen understanding through inquiry, our classrooms can become lively learning forums driven by student curiosity and the thirst to know more.

Lots of excellent points here about the importance of questioning. This post might also be of interest: https://www.middleweb.com/10734/number-one-close-reading-skill/

This post might also be of interest: https://www.middleweb.com/10734/number-one-close-reading-skill/

Excellent ideas. Thank you.