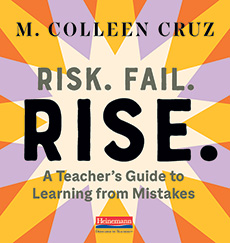

Creating a Culture that Welcomes Mistakes

By M. Colleen Cruz

From the time kids first step into school until the time they leave, we are telling them that mistakes are part of the learning process and that everyone will make them. Kids as young as five know the difference between fixed and growth mindset. And yet… I don’t know of a single educator who does not worry about how risk averse students are.

While it’s easy to point to the many things that might be going on outside of school to contribute to that, it is important to acknowledge that the students who will spend several hours trying to beat a boss on a level of a video game, making a different mistake each time, are often the same students who would rather choose an easy-to-spell word than something more complex but riskier to spell.

When we are brave enough to acknowledge that we might have some culpability in our students’ risk averse natures, we can move on to studying the habits and practices schools embrace that might be undoing our best mistake-welcoming efforts.

Let’s look at five simple things educators can do to purposefully create a mistake welcoming culture.

✻ We can remind ourselves that mistakes do not cost the same for everyone.

For many of us, including some students, mistakes – even huge mistakes – can have relatively temporary or light consequences. For others, even a small misstep like a uniform violation can carry devastating consequences.

Whether this is because of our race, class, position, ability or something else, as the leaders in our classrooms we must acknowledge that our own identity and experience with mistakes will affect the way we respond to the mistakes of others.

When we forget this, and either underestimate a student’s response to a mistake or believe that our responses are always justified and completely unaffected by identity, it can cause harm. When we center identity and experience in our thinking, we tread more carefully and are more likely to respond to mistakes, our own and others, in ways that are positive and risk-affirming.

✻ We can model mistake making.

Most of us recognize the wrong way to respond to mistakes we’ve made. Students have watched countless adults and children respond badly. But rarely do children see adults make mistakes and then name those mistakes–voicing over their responses to them in transparent and instructive ways. The next time you make a mistake in front of students, pause and name it. Model how to respond in productive and healthy ways. This might sound something like:

“Oh, Oscar – thank you for telling me I already read this chapter aloud last week! If you hadn’t, we would have spent our whole read aloud time re-reading when we meant to read forward! I appreciate telling me.

“And now I’m reflecting on why I made this mistake. And guess what? I see that I like to leave my bookmark at the start of where I am reading, and then move it over to my stopping place when I’m done. But I think what I did last week was forget to move it over. So – new habit. I am going to take the bookmark and place it on my lap so I won’t forget it and I can place it on the last page read.”

✻ We can create space for tinkering.

When we think of innovators, inventors and other creative types, one thing we often think of is a habit of mind to tinker, mess around, daydream and create in messy, bumpy, trial-and-error ways. For these thinkers, we expect them to require space and time for that sort of exploration and experimentation.

But, in school, with our ever expanding to-do lists, we are feeling the performance pressure and the urgency for students to gain necessary skills and increase achievement. The time we are willing to set aside for messy exploration is often small or even non-existent. Students are often taught a concept and then asked to practice it to mastery right away, with little time for mucking about.

When we notice students are particularly risk averse in a subject or skill, one classroom habit we can cultivate is to make time for tinkering in that content or skill.

► Kids freezing up in multiplication? Offer multiplication exploration centers.

► No one trying out new vocabulary in writing? Offer some morphology instruction followed up by tinkering time to find, explore and try new words out in a low-stakes conversation.

“Tom liked to fool around.” (Russell Hoban, How Tom Beat Captain Najork and His Hired Sportsmen

This not only makes space for risk-taking and helps students overcome their nervousness, it also teaches them that when we’re stuck, instead of shutting down we can spend some time fooling around with the new things we’re learning.

✻ We can value and celebrate process (over product).

Think about the last big class celebration you had. Whether this was during the pandemic or not, picture it. What were you celebrating? A holiday? The end of a unit? A finished writing piece? A science fair? All of these are wonderful things to have celebrations for.

However, it is also important to think about the intrinsic messages we send when we only celebrate holidays and culminating events.

Kids know we celebrate the things we value. When the only academic celebrations we hold are ones when projects are finished and we talk about how great those finished projects are, students get the message that the goal of these projects is to make the projects great, not all the great learning they did along the way.

Whether this is having kids find and annotate their most interesting computation error, or talking through the biggest problem they faced when engaged in makerspace, or having a revision celebration in writing workshop, teachers can intentionally plan celebrations to make sure they highlight the learning process and not just the culmination of learning. It will go a long way toward sharing the value of process.

✻ We can avoid over-grading.

While we are at it, we do need to be honest about the fact that grading is a major obstacle to creating a mistake-welcoming classroom. When students learn that an assignment will be graded or that they will soon be receiving a grade on a report card, you can guess to the minute how soon they will be asking “is this right?” With the exception of a few predictable risk-takers, the focus will shift to being concerned about the score – to the detriment of the learning.

Students know, despite our emphasis on how mistakes are part of learning, that those who make the fewest errors get the highest scores. The theory goes that grades inspire students to work harder, which will help them learn more, but this is rarely the case. After two-plus decades of being an educator, I have seen very few instances where grading caused students to expand their learning through exploration. Most often it has encouraged them to guide their learning to match what the grading system calls for.

Since many schools and districts are committed to grading, simply ignoring grading expectations is not always realistic. However, teachers can mitigate grading’s negative effects on learning by choosing to not grade, or lightly grade, tasks where mistake making and risk taking are paramount to the learning process.

Next on the list is…

As you’ve read this, you might have thought of more ideas for ways to plan, create and maintain a mistake-welcoming culture in your school or classroom. While fresh ideas are helpful, the most important action all of us can take is to intentionally move beyond the posters and spoken platitudes.

Let’s make sure that our classrooms really are places that welcome risk-taking in the name of learning, and expect and celebrate the mistakes that will inevitably show up where great learning is happening.

Colleen is also the author of The Unstoppable Writing Teacher, Independent Writing, and A Quick Guide to Helping Struggling Writers as well as the young adult novel Border Crossing. She is also a national and international literacy consultant.

I am absolutely an advocate of this, and it is a regular part of my Personal, Social, Health and Economic education development (PSHE in Great Britain) as well as reinforcing it in subject-specific lessons especially Maths.

However, for me the biggest issue is that school administrators don’t take the time to establish the same kind of atmosphere with the faculty that they expect from faculty to students!

So many schools have micro managers that get easily upset and/or dismissive if a staff member should suggest an alternative to one of their own ideas or plans. Many staff are bullied and afraid to voice an alternative option or opinion. This is far more pervasive than from teachers to students, in my humble opinion.