Helping Kids Develop Their Cognitive Immunity

By Gillian E. Mertens, Angela M. Kohnen and E. Wendy Saul

Gillian

What if we could vaccinate ourselves against misinformation?

Over the past year, vaccines have dominated the news, and many of us have learned more about the science behind vaccination and immunity than we ever thought we would.

But there’s another kind of immunity that is also relevant in our current situation: cognitive immunity.

Angela

Currently, two epidemics are endangering Americans: the COVID-19 epidemic and an infodemic the World Health Organization defines as an “overabundance of information – some accurate and some not – that occurs during an epidemic. It can lead to confusion and ultimately mistrust in governments and public health response.”

Wendy

As teachers and citizens, we recognize and resonate with this notion of the infodemic. Surely it is/was evident as we watched scientists, government officials, journalists, and even celebrities offer conflicting information regarding treatments, vaccines, masks, and lockdowns.

But the idea of an overabundance of information, some accurate and some not, is a worry which extends beyond the pandemic. Is there anything we might do in our classrooms to protect students against misinformation?

The Twitter Opinion Market

In a chillingly predictive vignette, cognitive psychologists Lewandowsky, Ecker, and Cook opened a 2017 article on misinformation with the following:

Imagine a world that has had enough of experts. That considers knowledge to be “elitist.” Imagine a world in which it is not expert knowledge but an opinion market on Twitter that determines whether a newly emergent strain of avian flu is really contagious to humans… In this world, experts are derided as untrustworthy or elitist whenever their reported facts threaten the rule of the well-financed or the prejudices of the uninformed. (p. 254)

While Lewandowsky and colleagues did not predict the precise information crisis wreaked by COVID-19, their insight speaks to how online environments enable the spread of misinformation and disinformation.

The information superhighway allows users to locate information at remarkable speeds – yet also facilitates the increasingly fast spread of misinformation and disinformation. Such an environment causes us to ask: what would a healthy cognitive immune system look like?

Cognitive Immunity

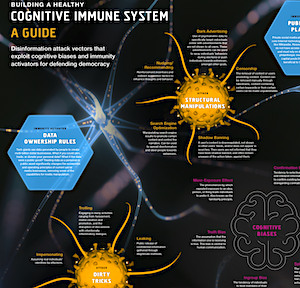

Cognitive immunity is not a new concept, and we certainly didn’t invent the term. For example, The Institute for the Future has created a detailed map of what a healthy cognitive immune system entails.

Although many of their recommendations are beyond the control of individual educators, they note that education has an important role to play in immunity-building.

Behavioral scientists have been using the metaphors of immunity and vaccination since the 1960s. While there are multiple kinds of vaccines, the end result is largely the same: a vaccinated person’s body has the immune system “memory” to fight off the germ.

Extending the vaccination metaphor to misinformation, then, would involve equipping individuals with knowledge, experiences, and techniques that provide mental defenses against the battery of misinformation and digital noise that users encounter online daily.

Vaccines are often a proactive step in eliminating disease in both individuals and society. Ideally, you get a vaccination before you encounter a virus or infectious bacteria, and the vaccination prevents you from getting ill. Therapies and drug treatments are also important medical tools, yet they are reactive, used after you are sick—and often they are applied too late to keep an individual from passing the illness on to others.

Fact-checking and debunking misinformation are akin to therapies or drug treatments – potentially useful tools for an individual to identify and correct misinformation (and resultant misinformed beliefs) once encountered, but often of limited utility for the society at large.

Inoculation, though, may help control the spread of misinformation before it can run rampant across our communities.

Practical Steps to Cognitive Immunity

For a time, research on cognitive immunity focused on protecting against misinformation about specific topics, such as climate change science, rather than on the techniques that make misinformation more likely to spread. However, new research has shifted that attention.

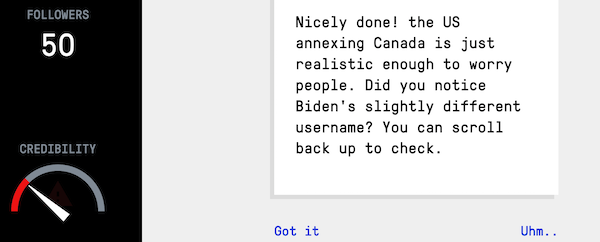

The creators of the gamified cognitive immunity website “Bad News” (screenshot above) describe their efforts as “pre-emptively exposing people to weakened examples of common techniques that are used in the production of fake news [to] generate ‘mental antibodies’” (see more here). The same team of researchers recently created a game all about COVID-19 misinformation called Go Viral).

In both games, the player assumes the role of misinformation disseminator within the controlled game environment. Because of this, the games are recommended for those over age 14 (Bad News) and 15 (Go Viral), and we encourage teachers to visit the games and the information sheets before deciding to use them in the classroom.

Yet we believe the ideas behind these games can be applied in all middle school classrooms, especially when paired with other generalist literacy activities. As we have written previously at MiddleWeb, many times individuals are misled by bad information not because they can’t fact-check but because they choose not to.

We argue that the generalist identity (the identity of someone who is skeptical, committed to accuracy, curious, and persistent) can override other identities and affiliations when one is faced with new information. In other words, the generalist identity can serve as a proactive measure to protect against misinformation.

Scaffolding information evaluation

While putting students into the role of misinformation creator may be problematic for middle school, teachers can help students assume the active role of evaluator, with a supportive teacher to model how generalists think through information evaluation.

All misinformation is not malicious in its intent – sometimes it’s the result of an honest mistake or even a joke. Teachers can find age-appropriate examples of viral misinformation using Snopes or other fact checking sites, or even through their own social media experiences.

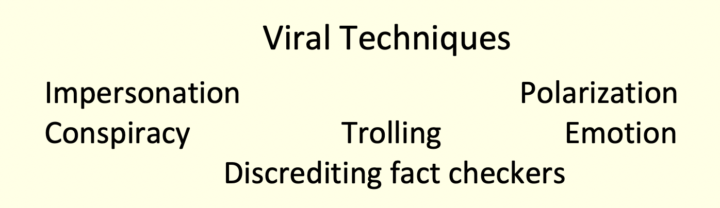

Importantly, we encourage teachers to guide students through their own evaluation process by highlighting some of the common characteristics of viral misinformation, including:

- use of highly emotional language,

- credentials (either real or impersonated), and

- presence of conspiracy theories (or information that casts doubt on accepted narratives).

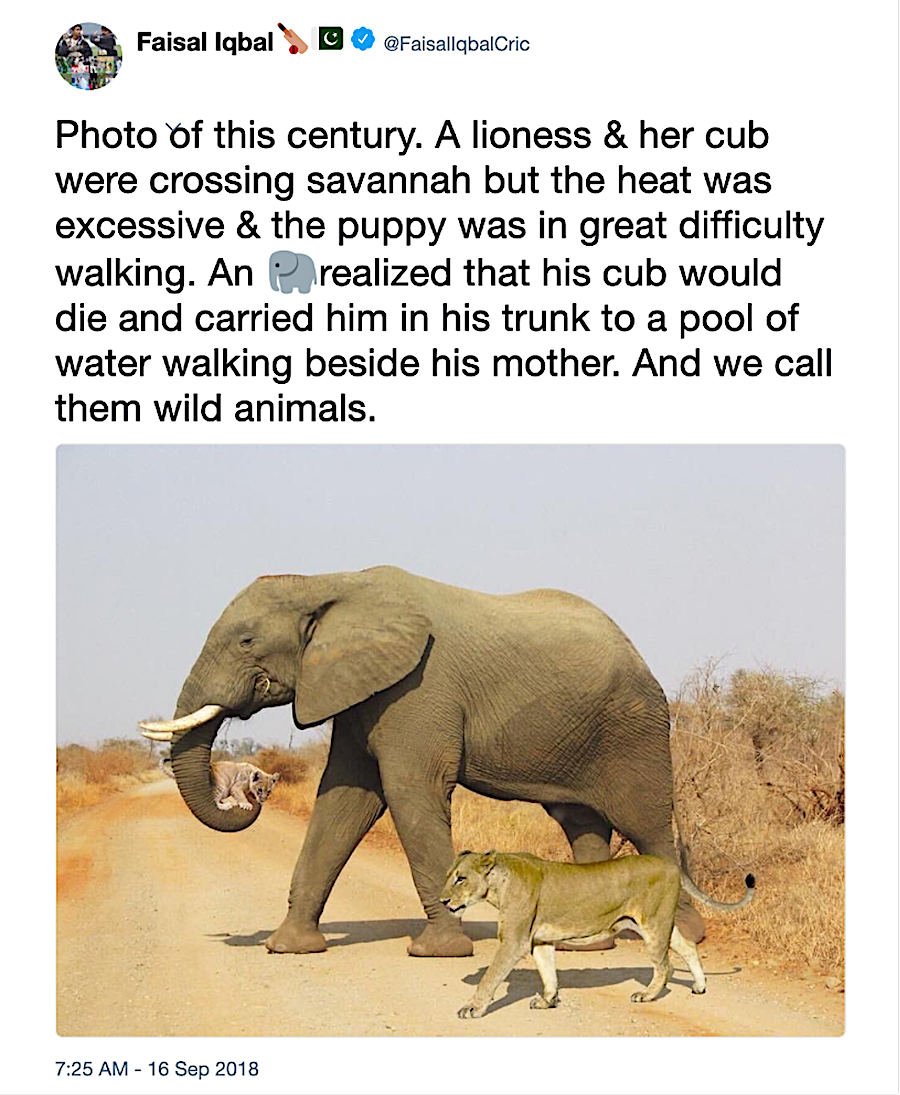

For example, Gillian created an activity that led 8th graders through an evaluation of a viral tweet from cricket star Faisal Iqbal (see the Snopes story here). The tweet (below) accompanied an image of an elephant carrying a lion cub in its trunk, declaring it a “photo of the century” and ending “and we call them wild animals.”

With Gillian’s guidance, students noticed their initial reactions – which ranged from “Awww, so cute!” to “Fake!” – and thought about why emotion leads tweets to go viral.

The conversation in Gillian’s class also led to a discussion of why we often trust images so instinctively, even when our logical brain tells us they can’t be true.

The key to activities like this is to do more than simply debunk the misinformation – the goal is to help students recognize the reasons the information was believed by so many people. Teachers may wish to keep a classroom list of strategies that lead to viral misinformation. The Bad News teacher’s guide includes several common techniques and links for further reading.

Vaccine Hesitancy

As with traditional vaccinations, some parents and students may be vaccine hesitant. In our experience, parents who learn of misinformation lessons at school are most concerned that students will be required to create social media accounts or engage on platforms that parents do not trust. And we’ve even seen stories where students have been asked to create misinformation as a learning experience—and the misinformation ends up going viral, with real consequences.

We stress that cognitive immunity activities, like current vaccinations, should not contain “live viruses.” In other words, the activities should be outside any actual social media platform, and students should never be asked to create harmful misinformation about real people as a learning activity.

And, in truth, this vaccine metaphor is for teachers, not for students. Learning this way doesn’t need to be framed as “inoculation” at all—in fact, it’s a lot more effective when it’s gentle and focused on discovery.

Also see

“Helping Our Students Identify as Generalists”

by Kohnen and Saul.

Gillian E. Mertens recently completed her doctorate in English Education at the University of Florida. Throughout her career as an English teacher, she’s loved exploring issues of credibility, curiosity, and metacognition with young learners. Gillian has taught 7th and 8th grade with experience teaching mainstream, gifted, ESE, and ELL students.

Wendy Saul received her teaching credentials from the University of Chicago and her PhD in Curriculum and Instruction from the University of Wisconsin, Madison. She taught middle school on the Lower East Side of New York City and reading, writing and children’s and adolescent literature at UMBC and UMSL. Saul’s interest in the world of science which her husband and friends occupy and explore resulted in a number of books and National Science Foundation grants, including Vital Connections: Children, Science and Books and Crossing Borders to Science and Literacy Instruction.

Angela and Wendy are the authors of Thinking Like a Generalist: Skills for Navigating a Complex World (Stenhouse, 2020).