Read Like a Reader, Read Like a Writer

By Jacob Chastain

Classes are filled with processes and procedures. Teachers everywhere have procedures for turning in work, sharpening pencils, when to ask to go to the restroom, and processes for how to work through complex tasks, such as breaking down test-like questions, complex words, or even starting a draft on a new piece.

Classes are filled with processes and procedures. Teachers everywhere have procedures for turning in work, sharpening pencils, when to ask to go to the restroom, and processes for how to work through complex tasks, such as breaking down test-like questions, complex words, or even starting a draft on a new piece.

Teachers understand the power of processes and procedures because both contribute to a classroom that functions properly and supports an environment conducive to learning.

As a reading-writing workshop teacher in middle school, I have become fascinated by processes and procedures that guide but do not limit, that support but do not hinder. In my own work I have tried to take such “stuff” out of the class so that I can have students focus more on the individual work they are doing.

I’ve tried to work in processes and procedures that operate as “out of the way” as possible so that they become more like habits my students develop than tasks or directives from me.

Enter: a process and procedure of thought.

The Workshop Mind

Workshop isn’t just a style of teaching – it’s a state of mind that shapes how everything in a classroom works. Mini-lessons become more about being a catalyst for thinking rather than being a command to think about something specifically. The work students do becomes more about how they process through complex ideas, emotions, and purposes, rather than just what is turned in on the due date.

This doesn’t downplay the importance of final products, of course, but rather shifts our focus as the lead learner in a class. Workshop is about the work students are doing now and about supporting them to go through that process to achieve at higher levels. Rather than focusing on the end product, we shift its role into being what we use to judge the effectiveness of the work that happened before.

But what procedures and processes support this line of thinking? How do we guide without restricting students in their reading and writing?

I have found one indispensable process and procedure of thought that is essential in a workshop. It has made a massive difference for my students and made their reading and writing lives that much deeper.

Read like a Reader, Read like a Writer

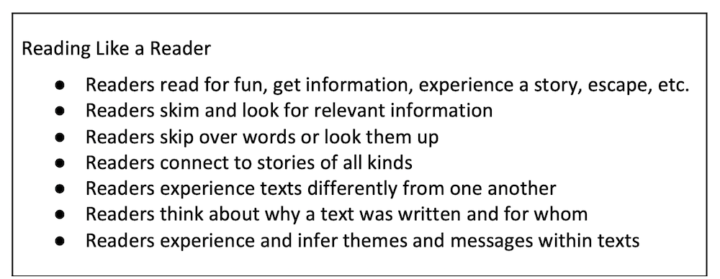

In my work with middle school students, I have discovered the power of prompting students with two phrases. Either I say, “We are going to read like a reader,” or “We are going to read like a writer.”

With these phrases I support students in thinking purposefully about the work we are studying. Whether it’s a passage, poem, novel, or peer writing, at the sound of either of these prompts, students pull up their background knowledge and engage at higher levels. These cues subtly support students in selecting the proper skills I have taught them, or that they have learned previously, for the task at hand.

For example, if we are reading a complex poem with lots of sensory language, I might prompt them with, “Alright class, on our first pass, we are going to read like a reader first. Let’s experience the poem and discuss what we get from it.”

Before this moment, I have taught students what “reading like a reader” means in my class. They know that we are looking for how a piece makes us feel and react, or what it triggers in our minds. When we read like readers, we are trying to understand what a text is saying to us and why.

We discuss and explain our thoughts with one another or as a class. We write down our observations, thoughts, or even questions we have about the piece being studied. As the teacher and lead learner, I have pre-planned questions in advance to prompt them towards our learning objective for the day as well.

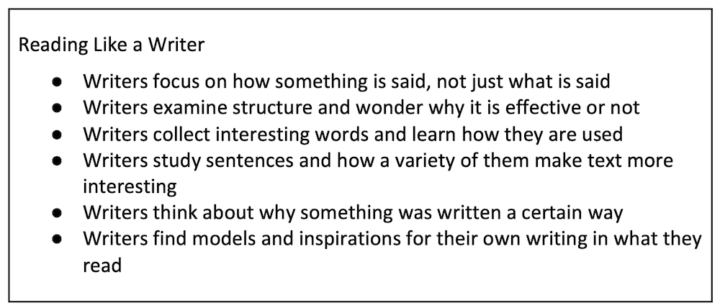

Once we have read the piece as readers, then it’s time to say, “Now, let’s read this as a writer.”

When we read like writers, we are trying to understand how the writer crafted a piece or excerpt to make us feel what we did or make us think what we thought. Questions in line with this act might be something like “What tools or techniques did the author use to get these reader reactions from us? Based on what we have learned as readers, was the writer successful in doing what they wanted to in the piece? Why or why not?”

We begin as consumers of words first. We read a piece as readers and get all we can from it, and then we flip our perspective to analyze the piece on a mechanical level.

By going about a lesson like this, a teacher can invite students into a multidimensional approach to understanding text. If a student can not only understand what they are reading, but be able to break away from being a reader and become a student of the craft as a fellow writer, they can answer any question thrown at them.

Better yet, they can process on deeper levels and grow more because of it, becoming dynamic readers and writers in their own lives.

Paradigm Shift

This process and procedure of thought is a lot like any you’d have in class. You set an expectation, teach the expectation, and practice over and over again until it’s automatic with students.

If we begin as early as the first lesson asking students to follow the procedure of thinking as readers and writers, we begin to shift their paradigms as thinkers around literature, poetry, and non-fiction.

Students begin to think deeper about all that they read because they are no longer just reading to read, or reading to get answers to questions, they are analyzing the text in a multidimensional way. They are receiving the information and processing, but they are also asking why this was written, why it was effective or not for them, and synthesizing information across both perspectives.

Students become active in their reading when asked to read like readers and read like writers, and are no longer just passive consumers of information. The procedure triggers a process they can follow over and over again, and it can apply to all kinds of texts.

Just as importantly though, this procedure and process doesn’t detract from their thinking. Many strategies can make the act of reading more about doing the strategy right versus reading and interacting at a deep level with the text at hand.

Because “read like a reader” is a process and procedure of thought, it guides without being restrictive. We are inviting them into an authentic reading experience guided by what we have already prepared them for.

Begin Naturally

To build this process and procedure into your daily routine, it’s not necessary to teach every aspect of what reading like a reader or writer means. Begin by asking what it means to them to read like a reader. What do we do when we read? Why? Then do the same with reading like a writer. What are the decisions writer’s make? Why?

Not only does this serve as a great formative assessment for you as the teacher to know where your students are in how they think about reading and writing, but you are also honoring where they are starting by using their ideas to guide their thinking.

Make these early ideas into an anchor chart or into notes students have and add to it over time. As you teach more strategies for reading and writing, your list will grow and students will have a deeper and better understanding of what goes into reading like a reader and reading like a writer.

By starting with what they already attribute to reading like a reader or writer, students will feel more connected and engaged with this process and procedure, making it more effective in the long run as your practice grows in complexity with what these phrases mean in an academic and even personal setting.

It’s the Small Things

This isn’t a process and procedure that you can buy online or take pictures of for “the Gram,” but it’s a powerful one. Truly, it’s often the small shifts in how we speak in class, what we focus on, and the repetition that lead to the biggest gains for our students.

Chastain currently teaches seventh grade English in Ft. Worth, Texas, where he lives with his wife and son. He holds dual master’s degrees in curriculum and instruction and administrative leadership from Dallas Baptist University.

Edutopia has republished portions of this article.