What Kids Gain When We Don’t ‘Teach’ Books

By Stephanie Farley

I go on to explain that what’s cool about my students selecting their own reading material is that it is an inclusive practice. Each kid gets to pick books that speak to their identity and interests. As a result, students actually read the books, which in turn means students develop takeaways.

In this way, I assert, my students get to experience what it’s like being a reader in the wild…forming connections, seeing relationships, and creating meaning. My job isn’t to dictate the meaning of specific books to my students; rather, my job is to create the conditions in which students make books relevant to their own lives, which is the whole point of literature in the first place.

At the end of my proclamation, people will usually nod and wander off, perhaps wondering about the “canon” and the standards and the SATs. However, if the people to whom I’m speaking also happen to be English teachers, they simply ask, “But how do you have discussions?”

This article is for the teachers who see the incredible value of allowing students to read what they want, but would like more details about the mechanics of teaching English without a shared text.

Targeting learning outcomes

The first issue to sort out is that of learning targets. In order to convince administrators that it is the right move to allow students to read what they want, you need to be clear about the learning outcomes you seek. Can you achieve those goals if students have different texts? Yes! Most standards are written broadly enough that a variety of texts will align with the stated goal.

For example, one of my learning targets for reading is “I can identify the big idea – or purpose – in what I read.” Neither the learning target nor the standard it is based on is about a specific text; rather, it’s about the student figuring out the purpose of whatever they read.

Once you’ve determined your learning targets, you can make a similar argument with your department chair, curriculum coordinator, or principal.

Widening students’ horizons

A second issue to address upfront is breadth of reading. While I am convinced there is no better way to teach kids to love reading than letting them read books of interest for school, it is also true that kids don’t know what they don’t know, so teacher help is needed to broaden horizons.

Consequently, I’ve collected a number of short stories and essays to supplement my 8th grade class’s novel reading. In this way I can easily target themes, writing styles, and literary devices that I want my students to learn.

Being able to rattle off an array of authors presented in English class – both “classic” and contemporary – has the added benefit of assuring dubious administrators!

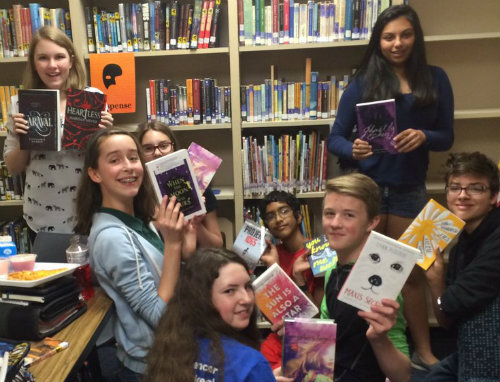

Piling up appealing books

Next, when the school year begins, I present my students with a list of suggested books. The suggestions come from my former students, my teaching partners, and the school librarians. I read every book on the list because I want to speak knowledgeably about the titles and help students find an appealing read.

I bring all the books from the list into the classroom and dump them on the floor. I have students sit around the books in a circle and handle them. They ask each other and me questions about the books, like “what is this about?” or “is this good?”

If it’s clear there is momentum in the room, I let the kids tell each other about the books, as this is the best possible way to begin. If information isn’t free-flowing, I’ll introduce a few titles and see whether I can generate any interest.

Several students will ask if they can read a book they have at home. I say yes and ask what it is. I tell students they can have a few more days to decide, but by some deadline, they need to tell me the book they’ve selected.

Responding to reluctant readers

At this point in the process, a few students will say to me, “I’m not that great of a reader.” I’ll respond, “Tell me more about that,” and we take it from there. Sometimes, a tutor or educational therapist is already in the picture and we’ll talk about how beneficial that is, while other times I’ll recommend audiobooks and/or professional support.

Still other times, the student really just means that they don’t like to read. That’s okay, too. For those kids, we talk about their interests and if there’s any reading they naturally gravitate to, like skateboarding magazines, serial online manga, or Reddit boards about their favorite video game. From there, we’ll agree on acceptable reading material for the purposes of this school project.

Knowing who’s reading what

Once every student has selected their books, I create a spreadsheet for myself listing the student, the title, and the month the book was read. This way, I can keep track of who has read what, watch for emerging patterns, and make suggestions as needed. Reading is assigned in “chunks.” Over a period of 10-14 days, students read 25% of their books. In the following 10-14 days, they’ll read the next 25% of the book, and so on.

I give the reading schedule in advance and say, “If you fall behind, it’s no big deal. Just do your best. You should still be able to complete the assignments even if you haven’t completed all of the reading.”

Because everyone is reading different books, we don’t have daily discussions. Instead, 4 times per book, when the reading assignments are due, students are assigned a small, in-class project to complete.

Structuring individual projects

The intention of the projects is for students to show what they know about the book. A typical first project is to build the setting for the book, complete with representations of the main characters. Some students draw a picture, some build a paper diorama, while others create a digital landscape. After this is done, all students present what they’ve made and take questions from their peers. Students like hearing about each other’s books and what each reader finds important about setting and characters.

A second project is usually about identifying the conflict, the third project is about identifying literary devices and character development, and the final project is about understanding the themes from the book.

In this fourth assignment – themes – students are also asked to consider how the book addresses the essential question for the class, which might be something like, “how can I be more awesome?” or “what makes life worth living?” Always, students present their projects to the class and we discuss them.

Having students share their realizations

Early in the year I teach students how to effectively comment upon each other’s work and how to use sentence starters such as “tell me more about what you mean by…”. By the end of the first book, students have built a sense of community through seeing each other’s work, hearing from one another, and talking about the big ideas in the stories they’ve read.

It doesn’t matter to the kids that they aren’t all reading the same story. What they’re interested in – and what I’m interested in as the teacher! – is the ideas in the books…the way the writer uses details of plot and character and setting to advance a theme, or how certain phrases or descriptions perfectly capture a truth about the world.

In their sharing, students are inspired by each other and develop theories and have epiphanies, just as they might if they had read the same work. And, when it’s time to read the next book, many kids will pick a book their classmates just finished! It’s like an in-person, super-tailored version of GoodReads.

Building reading and writing skills

While the inclusive aspect of choice reading alone is worth making the change, another element that all English teachers have to consider is how well their students read. The good news is that when students select their own books, they tend to pick books that are at or near their level.

While a few of my students elect to challenge themselves with, say, Octavia Butler’s Kindred – a book whose language most 8th graders find opaque – others are comfortably challenged by Justina Ireland’s wonderful Dread Nation. I trust my students to find the works that both entice and stretch them.

Writing about books is still in the picture as well. Not only do the students create projects about their books – which involve writing – but they also complete in-class assignments about what they’re reading. Additionally, my students often pick up the style of the authors they’re reading, which is excellent practice.

Students introduce unreliable narrators, twist endings, and elaborate sentence structures into their own compositions. Kwame Alexander, Neil Gaiman, and Kristin Cashore are highly effective writing mentors, so much of our class time is spent determining how to use the literary devices introduced by whatever authors the students have just read.

Implementing the choice process

The last detail I want to share about this process is that it took time to implement. I started slowly, with just a few choice books per year. Over the course of about 4 years, I edged out all required novels with choice novels. Along the way, I kept data in the form of student writing, grades, and student evaluations of the course to show my administrators.

I also had to convince my teaching partners this was a good idea, of course, but that was easier because once they tried the choice books, they saw the excellent results in terms of student learning and motivation. Choice in books is especially successful with those students who don’t like reading. One student said to me, “You mean I don’t have to pretend to read Lord of the Flies this year?” That kid was funny.

It’s a keeper

Ultimately, choice in reading is about student autonomy and motivation. I value choice because I value student engagement pretty much above all else. If I can make decisions that help students want to learn, then 90% of the work is done. Oh, and in case you’re wondering, my students have performed just fine on the SATs!

Stephanie Farley has been an English teacher and independent school administrator for 27 years. Interested in instructional design, assessment, feedback, and grading, She has served as a Mastery Transcript Consortium Site Director and has been on a number of California Association of Independent Schools accreditation committees. Most recently, Stephanie is coaching with grades 4-12 teachers and teaching ninth grade English.

Thanks for sharing this fascinating approach, Ms. Farley. Could you share more about what your daily ELA class looks like? Do you use ANY mentor texts? Do students ever all read the same grade-level text (even if not a book)? How do you teach them to write evidence-based responses to text? TIA for any more info you can share.

We’ll make sure Stephanie sees your questions, Sarah. Also – she says this midway through her post:

“While I am convinced there is no better way to teach kids to love reading than letting them read books of interest for school, it is also true that kids don’t know what they don’t know, so teacher help is needed to broaden horizons.

“Consequently, I’ve collected a number of short stories and essays to supplement my 8th grade class’s novel reading. In this way I can easily target themes, writing styles, and literary devices that I want my students to learn.

“Being able to rattle off an array of authors presented in English class – both “classic” and contemporary – has the added benefit of assuring dubious administrators!”

Hi Sarah,

I appreciate your interest and questions! Yes, my students absolutely read shared works by the likes of Roxane Gay (a favorite is “I Was Once Miss America”), George Saunders (we examine his 2013 Syracuse University Commencement Speech), and Kelly Link (“The Wrong Grave” is hilarious and 8th graders tend to enjoy it). The way my class works is that I assign long-term projects–such as to write a personal narrative, essay, or story about the theme of “adventure”–then my students have direct experience of an adventure (that I create), they read adventures like “The Wrong Grave”, and together we analyze the components of adventure stories so that they are fully prepared to write their own adventures. I directly teach big idea or theme, theses, details, description, and voice so students are aware of how to use these constructs in their writing.

As I mentioned in the article, students write about their chosen books, picking out sentences and paragraphs that are compellingly written or that reveal literary devices like unreliable narrators, plot twists, foreshadowing, or in-depth character description. Again, I’ve read the majority of the books they select, so if they get stuck, I can help them. I even have students select sentences from the books they read, copy them into a document, and analyze the sentences for meaning and grammar, so that students understand how authors create meaning through the choices they make about parts of speech and phrases.

Not every day looks the same in my English classes, but I do know that students finish the year feeling competent and confident about their improvement in reading and writing. I hope this helps!

With good wishes,

Stephanie