Pairing Graphic Novels with Their Text Originals

Dr. Jason DeHart is a scholar of graphic novels – and a North Carolina classroom teacher. Here he shares a three-step method he uses to engage students in both the YA chapter book Serafina and the Black Cloak and the book’s graphic adaptation.

By Jason D. DeHart

The first is that comics are not “real books.” This idea, if we are not careful, takes us down the path of only holding certain types of books in esteem; many voices and ways of composing are then left out.

The second myth is a little different and focuses on the pedagogy itself. That is – teaching comics is just like teaching any type of text.

I know, I know. I just made the case that comics are real books (and they are). However, given the composition of comics, we need to take a unique instructional approach. If you don’t believe me, try reading a graphic novel out loud to a class without finding a way to share the visuals.

Teaching a comic or graphic novel

Comics are combinations of words and images, with an interwoven relationship between these two elements that sets them apart from picture books. In this post, I follow Chase, Son, and Steiner’s advice from their 2014 Reading Teacher article and think about ways to initiate the teacher who has not yet decided how best to teach a comic.

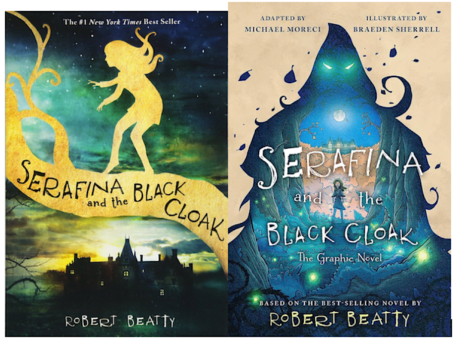

I’ll be highlighting Robert Beatty’s novel, Serafina and the Black Cloak and its recent graphic adaptation by Michael Moreci and Braden Sherrell, both published by Disney Hyperion.

A number of graphic novel adaptations of text-only books have been published and are available. They range from comics-based renderings of upper elementary/middle grades stories (e.g., The Crossover by Kwame Alexander and Dawud Anyabwile, Turtle in Paradise by Jennifer L. Holm and Savanna Ganucheau) to evocative and mature works for older readers (e.g., Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood, 1984 by George Orwell).

The ideas in this post apply to one text specifically but can be tailored for any text pairing you might choose to teach.

Step One: Recognize What Each Version Brings

In teaching Beatty’s novel and adaptation, my first move is to highlight what each version of the story brings. One affordance that a novel/graphic novel combined unit offers is the possibility for thinking about key scenes and how these are rendered in both forms. Beatty works in the world of prose, fashioning characters, setting, and mood from the words that he chooses. This is not small feat and is work worth noting. When he begins a chapter with the phrase, “The ax is gone” (p. 106), these words are chosen and their placement is key for building narrative.

One goal of mine is to disrupt any ideas about one text being more “booky” than another. I would recommend moving the discussion back and forth, highlighting the novel first, then the graphic novel. In this way, the adaptation is not always playing “backup” to the prose novel.

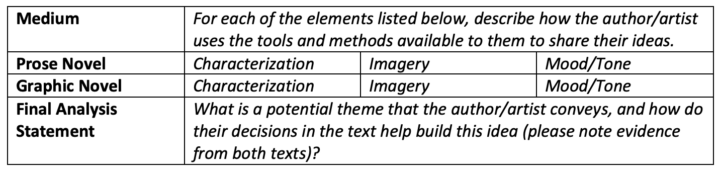

This working back and forth fosters comparison, and a graphic organizer/table like the one below can be useful for identifying elements. It helps students to think about how characters and designs match our expectations, yes. But there is more.

The design of characters and settings, among other literary elements, can act as a scaffold for readers who have trouble imagining scenes and moments in the story purely from the author’s words.

On the other hand, the use of visual design can be a fruitful place for analysis. Teachers can accomplish this in one stroke, with some follow-up conversation, through a simple and inviting question like What does the graphic novel add to your reading? We can also point to the choices from panel to panel and page to page, as when Beatty begins his chapter with a provocative statement.

I have found that there is not a single aspect of the literature or informational text standards for English/Language Arts that cannot be addressed with a graphic novel. With this in mind, teachers can refashion graphic organizers like the one above.

Step Two: Work Across Texts with Purpose (Slowly)

As we pursue cross-text comparisons, we can use an overhead projector/screen share of the graphic novel’s pages, take screen shots of particular elements, or use sticky notes with physical copies to do an intentional close reading of particular moments.

When I first began teaching, my nervousness and anxiety led me to speed through texts, sometimes reading works simply because I loved them. While it is wonderful to share books we love, I have found intentional choices to be all the more powerful in helping students develop key takeaways.

This kind of close noticing requires a necessary amount of pausing and waiting – all the more difficult if we teach online classes, but quite possible. Questions can be formed in relationship to the methods of the author and artist, just as they can be formed with the prose author and that version of the text.

Sample questions about the graphic version:

- What is the effect of this wordless panel?

- What happens from panel to panel?

- What mood is created by the images and colors?

- What alterations does the comics writer/artist/team need to make in order for the story to work?

- How do each of these approaches to the story achieve their purposes?

When Robert Beatty opens the novel with the description of Serafina opening her eyes and taking in the woodshop setting, a slow and close reading of this page can involve having students locate specific adjectives and phrases that help bring the visual to life in the mind.

From there, the author takes us to a description of what is happening in the character’s mind before dialogue begins. It might be helpful to point out to students that these are the very same words that the composer of the graphic novel used when they were creating a script and illustrations.

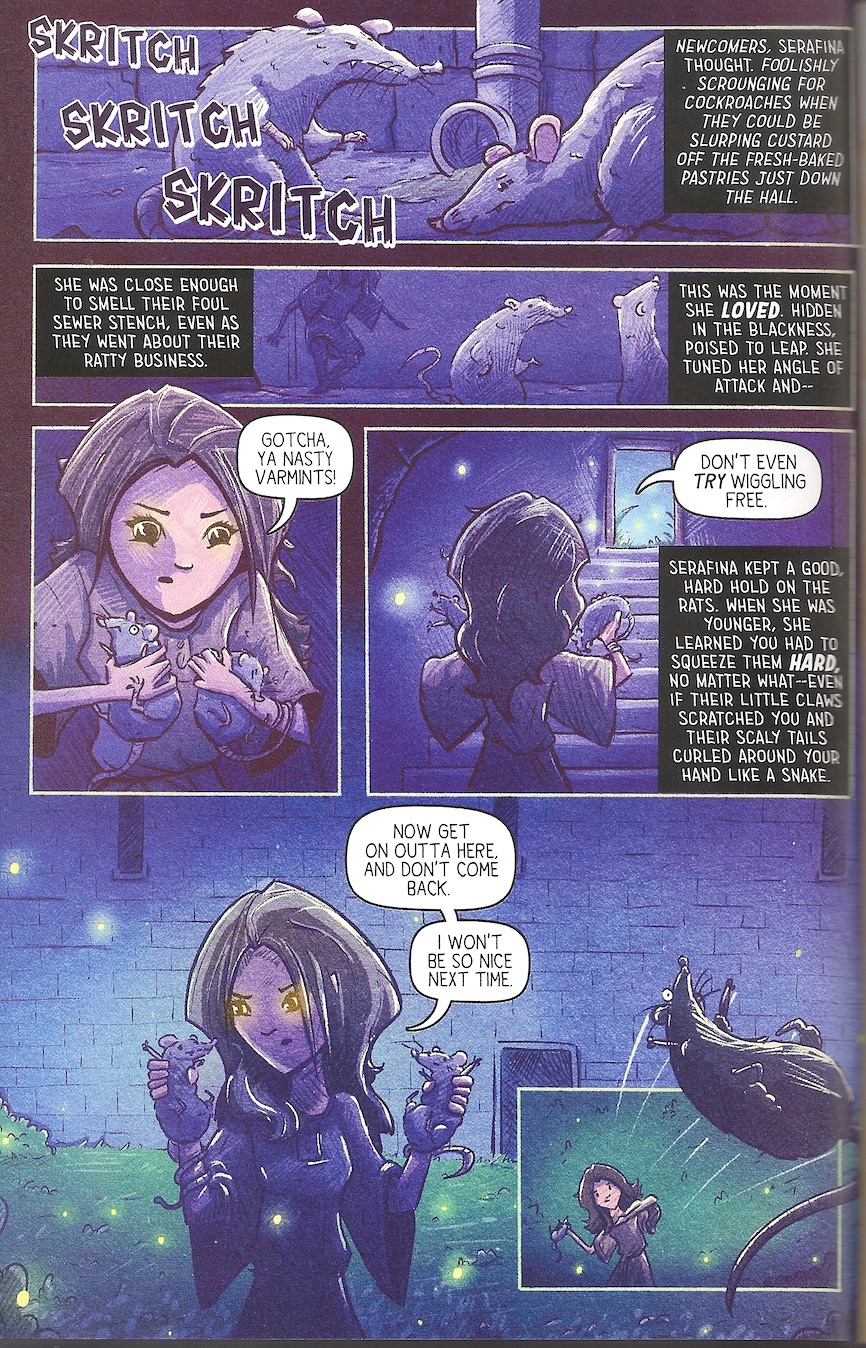

Graphic novel opening (above)

Prose novel opening: Serafina opened her eyes and scanned the darkened workshop, looking for any rats stupid enough to come into her territory while she slept. She knew they were out there, just beyond her nightly range, crawling in the cracks and shadows of the great house’s sprawling basement, keen to steal whatever they could from the kitchens and storerooms. (Chapter 1)

Beatty’s mood-setting text continues for pages as he begins to build Serafina’s backstory…then he returns to the present and describes how she seizes “two huge rats covered in greasy brown fur [that] had slithered one by one up through the drainpipe in the floor” and carries them to the edge of the forest. Here the graphic novel creators pick up the essence of Beatty’s language:

[from the comic]

(speech bubble) “Don’t even try wiggling free.”

(narrative box) Serfina kept a good, hard hold on the rats. When she was younger, she had learned you had to squeeze them hard, no matter what—even if their little claws scratched you and their scaly tails curled around your hand like a snake.

[from the novel]

The rats wriggled wildly, but she kept a good, hard hold on them and wouldn’t let them go. It had taken her a while to learn that lesson when she was younger, that once you had them, you had to squeeze hard and hold on, no matter what, even if their little claws scratched you and their scaly tails curled around your hand like some sort of nasty gray snake.

If time allows, teachers can dive more deeply into the process of comics-making, as well. Through close-up images of the character’s eyes, coloring and shading choices, and the use of narrative boxes, the graphic novel team of Michael Moreci and Braden Sherrell worked to bring this story to visual life in their vision of the story.

Step Three: Let the Comic/Graphic Novel Guide Your Assessment

Let’s take a brief look at the possibilities for composition with comics. I’ve mentioned the links to literature and informational text standards, but objectives about comparative media and design decisions are also included in many state standards.

Writing standards need not always be essay-driven, as students can benefit from multiple ways to compose. This range of writing and creating practices can benefit students who are not yet confident in their writing abilities, who may have trouble with some aspects of fine motor production, and who may find images and symbols to be effective means for communicating ideas they do not know the words for yet.

Visual composing and creating can also be a means for enlivening ideas about what is possible in writing, and these activities link strongly with the digital and image-based world in which we live. Teachers can work with readers of all ages and all aspects of literacy development to brainstorm the best ways to share stories.

In short, the novel and graphic novel pairing can be a scaffold or icebreaker not only for reading, but also for composing.

The invisible process of reading

Images are more than a way of creating comfort for readers – they are also a means of getting a glimpse into the invisible process of reading itself. By asking students to compose visually and to approach stories multimodally, teachers can develop a “shared vision” of what students are thinking about as they navigate pages – regardless of the type of text that is being used.

This kind of intentional work is about building readership and showing students, rather than just telling them, what it means to be a reader.

Dr. Jason D. DeHart teaches English at Wilkes Central High School in Wilkesboro, North Carolina. He taught English Language Arts to middle grades students in Cleveland, Tennessee for eight years, earned his doctorate, and served as an assistant professor of reading education at Appalachian State University before returning to his first love, the secondary classroom.

Jason’s work has appeared in Edutopia, SIGNAL Journal, English Journal, The Social Studies, and the NCTE Blog. See all of Jason’s MiddleWeb posts here – including a 3-part series with teacher and school librarian Jennifer Sniadecki on using picture books with middle level readers. His website Book Love: Dr. J. Reads offers book reviews and author interviews.