Tool to Help Students Analyze History Texts

A MiddleWeb Blog

by Jody Passanisi and Shara Peters

by Jody Passanisi and Shara Peters

We can assign reading to students all we want, but this doesn’t mean that students will process and understand the information that they read. In history and social studies, we have an even bigger challenge: students need to comprehend expository texts, which they tend to have a harder time connecting to.

The questions we want to address in this blog post are: How can we get students to understand the content of what they read? And equally if not more challenging: How can we get them accustomed to inferring information from text?

The traditional way to check for reading comprehension in history class has been to have students answer the textbook-provided questions at the back of the chapter. These questions tend to be lower on the Bloom’s taxonomy ladder, and the students soon become adept at scanning a chapter for the one “right” answer.

Tools for thinking about text

When devising how we wanted to hold students accountable for reading deeply, we realized that this did not align with our teaching philosophy or methodology. We want students to understand what they read, but also to be able to analyze what they read, to ask questions, and to make inferences from the text.

We hoped to be able to both supply students with the tools to be more engaged with text, and provide them with a metacognitive vocabulary that was developmentally appropriate.

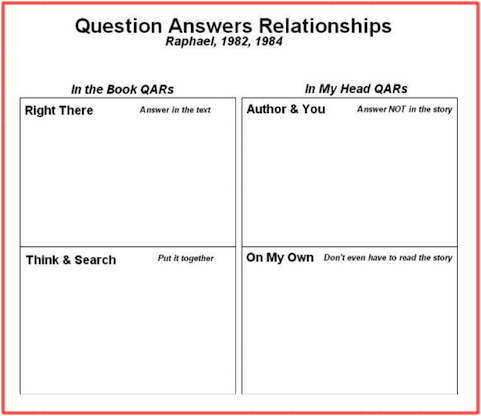

To that end, our colleague and fellow MiddleWeb history blogger Aaron Brock suggested we use the QAR (Question Answer Relationship) reading comprehension strategy. The most important feature to this strategy is that the students craft and answer their own questions.

How QAR works

In a nutshell, this reading strategy allows for students to learn an easier vocabulary for differentiating between levels of thinking. Level 1 questions are “right there” in the text and can be quoted word for word. Level 2 questions require a gathering of information — the answer is in the text, but in a few different places. Level 3 questions are inferential. The answer isn’t in the text, but is based on the information in the text. Level 4 questions are broader general questions dealing with the larger themes of the text but not with the specifics of the text itself.

While teaching this strategy requires a great deal of scaffolding, the pay-off is definitely worth the time. With QAR, students figure out a vocabulary for organizing both explicit and abstract concepts, are able to better monitor their own comprehension while reading, and can think about the text on multiple levels.

(1) The answer they are looking for is not explicitly stated and they will have to make an inference, and

(2) They will be able to figure it out, because it’s just Level 3. It’s achievable for them.

This kind of experience gives the students a sense of self-efficacy when reading a text; they can create their own questions, and have the vocabulary for answering any question thrown at them. This kind of categorization has long been the way that human beings make sense of the world around them, but it is not often that we are metacognitively aware of this categorization.

It makes sense that students would feel more confident once categories are in place for understanding how to read text. The metacognitive aspect allows students to take charge of their own learning processes.

Tweaking the QAR process

QAR is not flawless, however. We have noticed that when students focus on writing and answering questions about the text, they can become focused on the details of the reading selection and miss the overall gestalt of the piece.

We realized this recently, and we are planning to augment the QAR process slightly: before students begin writing their questions, we are going to require them to state the main idea of the text selection. When we know they have created some kind of overview of the information, we can then help them move on to more detailed work.

That’s one of the strategies we have devised. How do you teach students to understand what they read in history class?

Thank you for this post. I am needing as much help as I can get, in that my students are not only not interested in reading, but not interested in history.

Please share other tips.

I am getting your book on Kindle now.

Very good. I am implementing QAR in my GED classes.