José Vilson’s New Narrative

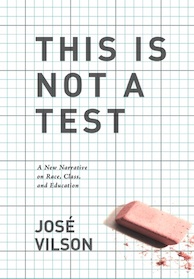

This Is Not a Test: A New Narrative on Race, Class, and the Future of Education

By José Luis Vilson

(Haymarket Books, 2014 – Learn more)

Let’s listen in.

“Do you think we’re going to pass this test?” Emilia blurts out.

Instead of my mundane Mr. Vilson answer (“Of course, you’ll be fine! And don’t worry about it. It’s only a diagnostic test anyway!”), I let my inner Jose out.

“Well, let me see.” I flip through the pages. “This one we did, this one we didn’t, oh boy, this one, umm, yeah, we did this one, yes, yes, no, no, yes, yes, yes, maybe. . . I’d say about 60 percent of this we’ve covered.”

“Then why do they want us to take it?”

“Because they’re mean.”

“No, you’re mean.”

“True, but they’re meaner.”

They laugh.

“No seriously, I can’t understand why they’re making us take this stupid test if they know we’re not going to do well on it.”

“To be honest, me neither.”

“What is this for, anyway?”

Mr. Vilson takes over where Jose left off. “Well, teachers would like to see what you’ve learned and what we need to work on in order to get you ready for the big test.”

“Oh, I see what you mean. But you think this will help us graduate.”

“Well. . .” I waffle here. “Yes, it does.” Expletive.

* * * *

There’s always the one student who does the bad-kid trifecta: shakes the seat, snickers loudly, and yells, “I don’t wanna do this bullshit!” Jimmy came in half an hour late, with one of the deans trailing him. I heard a get-in-there follow him down the chambers.

Mr. Vilson, the professional me, says, “Now, why do we need to yell all that?”

“I don’t want to take this test!”

Jose thinks, Good, me neither.

Mr. Vilson says, “I understand, but don’t you want to do well?”

“No, I don’t want to.”

“You do know how important this is, right?” Not very, kid.

“I don’t care!”

“Yes, you do.” We don’t either.

“I wanna go home!”

“Now, is it necessary to make all that noise while we’re trying to start this test?” Rebel! Please rebel!

“Fine, I’m going to put my head down because I’m not doing this shit!”

“Okay. I’ll still have your test ready for you.” It hurts us almost as much as it hurts you.

I start maneuvering through the aisles, around desks perfectly aligned in units,handing out bubble sheets and exams with natural ease. I start reading the instructions: “Today, you will take the New York State Interim Examination in Mathematics.”

* * * *

I can’t help but feel that when my students walk out of their exams, they aren’t just frustrated by the inordinate amount of testing they’re subjected to. They’re starting to sense that the process of schooling in and of itself was not actually designed with them in mind—a feeling those of us born into poverty and racism know all too well.

By teaching students of color that the best way to succeed is to respond to tests the way the state demands, determine the validity of an argument under the state’s rules, and examine essays only if they follow the state’s standards, we are creating education via deculturation, or stripping a culture, instead of transculturation, the merging of cultures.

We didn’t land on education reform. Education reform landed on us.

But these thoughts are for another time. “Please put your pencils down,” Mr. Vilson says. “You have completed your test.”

Jose thinks, Actually, far from it.

A voice shaped and raised by connection

“The parallels between the lives of kids in impoverished neighborhoods and those of rats do not escape me,” Vilson says. “They help explain why I write as I do. Those who have lived similar experiences to mine understand why we keep a guarded demeanor even when expressing our deepest emotions.”

Vilson further developed his cautious persona on the streets of Lower East Manhattan, still the wrong side of town in the late 1980s and 1990s when he attended public and Catholic schools. Walking there could be “an exercise in survival, even for those of us who considered ourselves nerds or outcasts.”

Significantly, Vilson observes here that “tired of waiting to be heard, many of us have created our own spaces, lest we too get washed down the sinkhole.”

In his own case, some of his most important spaces have been built using social media and the technologies associated with 21st century life, including the Internet, where he is today a highly visible, thoughtful and progressively outspoken commentator on three critical American cultural issues of our time, identified in the subtitle of his book: A New Narrative on Race, Class and Education.

While Vilson may have struggled some to bring his social-emotional side to the surface as he wrote This Is Not a Test, he has been largely successful. I know this not only from reading his book but from a personal relationship that needs to be noted here.

A brief but full disclosure

I first got to know José Vilson “virtually” in 2009, when I helped recruit him into the national Teacher Leaders Network, a program of the Center for Teaching Quality (where he is now a member of the board of directors). As then-editor for TLN’s “teacher voices” initiatives, I worked with him and many other teacher leaders to develop and publish articles about school. We did eventually meet F2F at CTQ headquarters several times, but not surprisingly, email and Skype proved to be our preferred means of communication.

Later, when I and my partners launched the “new” MiddleWeb (founded in 1996 and reinvented in 2012), we drew on Vilson’s skills as an early WordPress adopter and part-time website developer (he has a B.S. in computer science from Syracuse University) to help us build our own internet outpost.

Over the course of time, I have seen drafts of some pieces of this book, and as Vilson notes in his Acknowledgments, offered some encouragement and advice. But the finished product is the result of several years of writer’s sweat on his part, and the support of his excellent editors at Haymarket Press. So I’m comfortable writing about the result here.

Part autobiographical – all educational

While This Is Not a Test is part autobiography, it is all about learning, with several unifying education themes woven throughout its 220 pages. The two dozen chapters (divided into three sections) have the feel of short essays, enriched with Vilson’s blogger sensibility and his need to tell stories.

We first follow Vilson through his K-12 years, including his time spent at Xavier High, a well-thought-of Catholic school where his hopes for racial harmony were dashed by the bitter sarcasm of a racist teacher.

By that time, I had played the trombone at the Columbus Day Parade, taken on the role of Superman at the last minute for the freshman play, fundraised for the David Cone Foundation, and volunteered in the pediatric unit at New York–Presbyterian Hospital. I had been included in the Who’s Who Among American High School Students collection. Yet I still found myself wondering who the hell I thought I was.

Vilson’s time at Syracuse raised his awareness about many things (as our college years tend to do), including the need to speak out about race and class issues; the lack of satisfaction likely to be found in a computer-oriented career, and the weak teaching skills of many college faculty:

My math classes didn’t go much better: I got lost in the one hundred–to-one student/teacher ratio and my eyes glazed over regardless of whether I sat in the back or the middle of the dimly lit auditorium. I struggled with a C average in those classes, the whole time thinking, “I can teach this better. Much better.” I usually took a nap shortly after that thought.

After (somehow) graduating from Syracuse with the computer degree in 2004, and spending some time doing unsatisfying work (data entry, while living with his mom), Vilson began to find his way toward the teaching profession. Back during his senior year, his Teach for America application was rejected when his sample lesson on exponents failed to shine in front of 15 other applicants “who knew this material rather well.” A year out of college, he now sought to become an NYC Teaching Fellow. After running the admissions gauntlet, he was first denied entry, then two weeks later NYCTF reconsidered and he was accepted into the program.

Readers can follow Vilson’s adventures through his sketchy preparation as a middle school math teacher: six weeks of pedagogy, several graduate courses, and a brief summer internship at the very school – IS 52 in Washington Heights – where, come September, José would morph into Mr. Vilson, and his idealistic illusions about the “call to teach” would begin to first degrade and then transform into something fiercer, more meaningful and more lasting.

Classroom stories; growing advocacy

In the middle third of Jose Vilson’s book (Part 2), those of us who love classroom stories that awe, inspire and even depress us will find what we we are looking for. An early version of the chapter “A Homeroom Is a Home” was published here at MiddleWeb in 2012, and is still a good sales piece for this book – showcasing both Vilson’s ability to laugh at himself, and his insights into the promise of good professional relationships, the stolid absurdity of school bureaucracies, and the joy and heartache of public school classrooms crowded with wonderful kids.

Since these first days, Vilson has found himself in roles as middle school math teacher, instructional coach, master’s degree holder (mathematics education, CUNY) – and increasingly, restless educator. Part Three of This Is Not a Test chronicles his rise into the visible world of education commentary and advocacy, accelerated by the parallel growth of connected educator communities, social media and the many websites and virtual publications hungry for meaty and sometimes provocative content.

We learn of his participation in the Save Our Schools march in Washington, his TEDx talk on teacher leadership and voice, and his growing criticism of oppressive test-driven reform strategies disproportionately visited on the poor and on children of color.

Vilson & students at Yankee Stadium

In truth, in this period from roughly 2009 to the present, Vilson’s journey reflects the path taken by other committed younger teachers who are using their voices to anchor themselves in an often poorly led profession, buffeted by policy winds that wear on the most dedicated of souls. Some of us, Vilson tells us, must stick with this – and who more so than the rarest of educators, the Black Latino male middle school teacher.

As a teacher, Vilson says, he brings his own experience into the schools and classrooms where he works among students whose childhoods in the streets of Inman/Washington Heights are not unlike his own. It “makes lessons more profound” for children and adults alike, he says, citing Paulo Freire’s description of the cyclical nature of being a student and a teacher, in his Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

Vilson’s frank appraisal of the state of American public education may make some readers uneasy. So be it. He recognizes he was lucky, and most kids with his history will not be:

It always goes back to the same root: our educational system is meant to keep certain people docile and uneducated. These simple changes we ask for, like character development, extra accommodations for students who struggle with state tests, and a more supportive school system as a whole for all parties involved, are always regarded as “too expensive” or “pending” some litigation that usually gets drowned out by some other mess. Some of these simple adjustments may have worked in individual schools, but as a system, we’re just not doing well.

However, he is not despairing in his summation. His somewhat existentialist view comes through in a series of “tips” he shares from his 32-year old perspective, prefaced this way:

So what can we do? Maybe that’s the better question. After a recent conversation with a younger teacher, I thought I’d list some things that might be helpful with the socio-emotional part of this education process. I’m learning along the way, so suggestions and comments are welcome.

Vilson, a Millennial in every way that matters, tells me he thinks GoodReads is a good place for that.

Something more profound

He says it in powerful and compelling ways in This Is Not a Test, illustrated by stories from his own life and the lives of his students. Vilson’s deconstructed anecdotes cut through the platitudes of politicians and the endless alibis of central office admins, into the heart of America’s unresolved contradictions: public education and democratic principles; equity and privilege, race and class.

It is, indeed, a new narrative, spoken by a still-young teacher whose voice rises from the very center of urban America. As he says in his conclusion, “A Note from This Native Son” —

At its most revolutionary, the collective of women and men of color in any field see themselves as the spiritual mothers and fathers of those who seek to come afterward. As a teacher of color, sharing a lived experience with your students makes it imperative to do your best for your students.

… My job is to lead them on the path to success knowing full well that, systemically, the odds are truly against them.

In his book Possible Lives, Mike Rose tells us that “public education is bountiful, crowded, messy, contradictory, exuberant, tragic, frustrating, and remarkable.” Jose Vilson’s must-read book shows us just how true these rich adjectives really are – and where we might find courage to do something about the tragic and frustrating parts.

This Is Not a Test is available at Amazon and Barnes & Noble. If you order it from Haymarket Books, you’ll support the enterprise that made this book possible.

A wonderful summary. I can’t wait to read the book. I am a 51 year old, first year teacher. I also happen to be a white, male in a small rural county in southeast Georgia where our student population is about 50/50 but our faculty includes only one African American male. I appreciate Mr. Vilson’s perspective and applaud his leadership. Our children are struggling in a system which does not consider them, let alone represent them.

Thank you, Dave. As a native southerner and a journalist who’s written often about rural schools, I too see the surprising connections between Jose Vilson’s urban experience and the educational plight of rural children in poverty. Although I know that many dedicated educators are working to change things, the message often heard by these kids is: “You don’t matter.”