Taking the Struggle Out of Group Work

A MiddleWeb Blog

by Jody Passanisi & Shara Peters

by Jody Passanisi & Shara Peters

Most history and social studies teachers understand the value of group work, especially now, in the era of collaborative learning.

Most of us assign group work. And most students, at one time or another, struggle with it.

These struggles are often universal in theme:

I do all the work, so-and-so doesn’t do ANY work.

I don’t like working with ______. We can’t agree on what to do, can’t we just do it alone?

I want to work with ____ instead.

What’s going on here? It’s true that often one or two students in a team do most of the work. But can that be ameliorated?

How we help groups work together

A colleague, Jacob Hall, studied group work for his master’s project at Mount St. Mary’s College in Los Angeles. He found in his research that assigning a pool of points for a team, say 40 points for four students, and having the students divide the points up depending on who did which percentage of the work, was effective in raising students’ participation in a group project.

A colleague, Jacob Hall, studied group work for his master’s project at Mount St. Mary’s College in Los Angeles. He found in his research that assigning a pool of points for a team, say 40 points for four students, and having the students divide the points up depending on who did which percentage of the work, was effective in raising students’ participation in a group project.

We have tried this multiple times, though not for every group project, and each time we are surprised at how honest the students are in their responses.

Most often, the students who did not do their share of work (“10 points”), know it – and they also know who picked up their slack. A student may say on their anonymous card/email that they did only six points of work, but a teammate did 14.

This also goes a long way in placating the students who feel like they have shouldered the brunt of the work as participation points are then factored into the whole project grade.

Moreover, the students realize that there is a tangible effect if they do not do their work. Their 10 points did not go away. Someone else had to do their share. Someone else stepped in and took those points.

Tracking participation with digital tools

Another, very quantifiable, way of discerning and holding students accountable for what they accomplish during group writing/projects is using Google Drive to track participation.

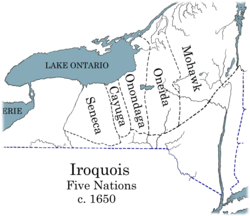

Recently, Jody had her student teams collaborate on a paragraph about the influence of the Iroquois Charter on the Constitution. When she noticed that two students in one team were doing the bulk of the content discussing — and the two other students were doing the bulk of the off-topic talking — she checked the revision history on their Google document. Sure enough, the students talking about off-topic items hadn’t done any work in the past 15 minutes.

Recently, Jody had her student teams collaborate on a paragraph about the influence of the Iroquois Charter on the Constitution. When she noticed that two students in one team were doing the bulk of the content discussing — and the two other students were doing the bulk of the off-topic talking — she checked the revision history on their Google document. Sure enough, the students talking about off-topic items hadn’t done any work in the past 15 minutes.

While it does seem a little intense, perhaps, to quantify contributions by tracking a counter, it really does allow this subjective experience to be concretized in a small way. Jody simply mentioned to the students in question what she’d noticed, and they refocused and jumped back into the writing.

Teamwork is stronger than “group work”

The most important thing about collaborative work, we have found, is making the students metacognitively aware of their role in a team.

Like Aaron Brock, our fellow MiddleWeb blogger, we call the groups “teams” so that the students feel more invested in their work together–identifying themselves as all on the same side, working for a common goal.

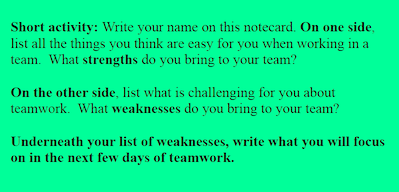

At the beginning of the year, after some small group work and before really intense group work, we have them reflect on past experiences, what has worked, what hasn’t, what role they tend to play in a group, what their goals are for themselves in group work.

This discussion, of course, doesn’t solve every problem, but it does give teachers and students some common goals and a shared vocabulary with which to frame the the work they will be doing collaboratively in the coming year. And when good intentions and the solid foundation break down, THAT’s when we use the point system.

How do you hold students accountable for group work in your social studies and other classes?

In my classes (middle and high school and adult ed) I use a variation of the 40-point system identified in the article. Each time I start a project, I begin with a review of expectations for working in groups, as well as a reminder of why working with others can be a benefit for student learning. I also clearly review the project stages and expectations and rubric. Once the project has been completed, I assign the entire group a single group mark based on the project rubric/evaluation form. For each student, this “whole group mark” comprises 50% of their final mark (rationale: they were part of the group, and the group earned this mark).

I then go through a self and peer feedback process whereby I use a simple math formula to identify “Total Group Points.” This formula is simply [number of people in the group] x [mark out of 100 earned by group] + [1 point for each person in the group]. For example, a group of 3 that earned an 80 would have 243 points (3 x 80 + 1), while a group of 4 that earned an 80 would have 324 points (4 x 80 +4). I then ask each person to divide the “Total Group Points” among the group members in a way that makes sense to them, based on what happened when the group did its work. I ask them to “use the numbers to describe reality.” These numbers are written down on a sheet of paper that is given to be privately. I then use the student-generated data and my own observations to assign each individual group member a second mark out of 100, their “individual contribution to the group mark.” Their final individual mark for the project is [group mark] + [individual contribution to group mark] divided by two.

A couple of quick additional comments: The [+1 per person] addition is actually pretty key. This allows a group that was ALMOST completely equal in their workload to either give an extra mark or two to one person without bringing other people’s marks down or to give everybody an extra 1 point, which I am okay with if they were actually that committed to pulling an equal workload. As importantly, in addition to submitting the peer and self-assessments, they also need to give a comment or two to explain their mark assignment…and the sheet also has room for additional comments, which are occasionally needed to address the complexity of issues that can emerge in group contexts. It is also key that the teacher assigns the mark, while the students simply contribute data…this takes some of the blame and frustration away from group members when someone ends up with a deserved mark they are unhappy with—they can’t blame their colleagues as easily when the teacher is the one who assigned the mark. This also provides opportunities for a conversation as well, which can be a good thing. My students have consistently stated that this is the “fairest” system they have seen. It takes time, but it is worth it…and the payoff usually comes the NEXT time our class does a group project…

Sean, thank you for the detailed explanation of how you deal with this issue in the classroom. Will have to try it!

Great post and fantastic ideas about having students/teams own their work and responsibility! In addition to Google Doc monitoring, I would love to know other ways to assess students’ contributions to collaborative work (how as the teacher I can discern who contributed what to a section in the document) without assigning sections to students. Any suggestions?

Thank you so much for reading and commenting. Ariel, that is the million dollar question, right? To me, the easiest would be with Google Doc monitoring, but another option is a longer analysis of individual contribution–a reflection of some sort–that asks students to identify the individual parts that they did in the context of the larger project. They could also talk about whether that breakdown of work was effective in getting the project done, and whether they would have organized the parts in a different way if they had to do over again. It would require honesty and self-disclosure, but that kind of detailed reflection would be good for them in terms of the meta-cognitive aspect, too.

What about having each person in a team volunteer to be responsible for a certain section of the project? The grade could then be based on total team presentation with a percentage of the grade coming from the section they chose to present. That way students are graded as a team and their individual effort.