The ASCEND Saga: Respect

This transformational story begins on the day Elena Aguilar asked 6th graders to use her first name. It’s the first in a series of stories about a remarkable public school experiment in the Oakland (CA) Unified School District.

Who Has Power in a Sixth Grade Classroom?

Who Has Power in a Sixth Grade Classroom?

by Elena Aguilar

“My name is Elena Aguilar,” I told my new students on their first day at our new school. “Call me Elena.”

My 48 sixth graders looked confused. I continued: “Why should you call me by my last name if I call you by your first name?”

“We always call teachers by their last name,” said a boy.

“Why?” I said.

“I’ve been taught to respect my teachers,” said another boy. “Isn’t it disrespectful to call you Elena?”

“Is it just our status alone that merits respect?” I asked. “The fact that I went to college, got a piece of paper that gives me permission to stand in front of you today?”

“Yeah,” called out a girl. “I had a teacher in third grade who used to cuss us out, make us put our heads on our desk for an hour and she’d sit and read magazines. Why should I respect her?”

“Ok, so what deserves respect?” I asked. “Talk about it at your table groups. You’ll have 10 minutes to create a list of your ideas and then share with the class.” The room got loud.

How students addressed me was within my domain of control as a teacher and I was intent on shattering this hallmark of hierarchy. My mission was transformation—and there was no way to do this without addressing traditional power dynamics in the classroom. I would start with the way that my students and I addressed each other.

We created a small, autonomous school

In September of 2001, I was one of a group of teachers and community members who started ASCEND, “A School Cultivating Excellence, Nurturing Diversity.” This public K-8 in the Oakland (CA) Unified School District was born as a “small, autonomous school.” We opened as an alternative to the huge, impersonal, overcrowded, chaotic institutions that were the norm in our district and that pushed our students out onto the streets by the thousands (at that time, the dropout rates were estimated at over 50 percent in our high schools).

At ASCEND we would know all of our students and their families, attend to social and emotional learning, integrate the arts into all content areas, and offer a model of instruction called Expeditionary Learning based on an Outward Bound framework. Approximately 70% of our predominantly low-income students were Latino, with the remaining students drawing from African American and South East Asian communities.

My 48 sixth graders were the founding middle schoolers at ASCEND. (We started with grades K, 2, 4 and 6 and added a grade level each year.) I taught history and English; another teacher taught science and math. I looped with my students for three years, through their 6th, 7th and 8th grade.

I made positive assumptions

I had never taught middle school before—I came from elementary—and this made me anxious as I planned during the summer before ASCEND opened. However, I remembered my own middle school experience: I was bored to death and teachers underestimated what I knew or could do. This led me to make some assumptions about my kids before I met them: that they had the capacity to grapple with big ideas, to be pushed really hard to think and produce and work at a level that was far beyond what anyone thought they could do. I wanted them to think until their brains dripped with sweat, and I wanted them to think about power.

That was the theme of our year-long study: Power. Our primary guiding question was: Who has power and how is it wielded? A set of sub-questions focused our inquiries:

- Who had power in the ancient world?

- What kind of power does a 6th grader in Oakland have?

- What kind of power do you have if you can tell your own story?

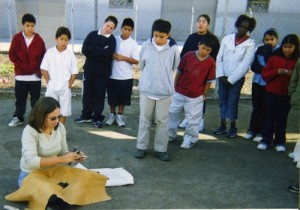

I designed exercises to give students an appreciation for their ancient ancestors. That’s what Suzanna learned on the day she sat in the courtyard for three hours trying to make fire with two sticks or when we painted in the light of a flame in order to get a sense of what ancient cave-painting artists experienced.

We talked about power

“When 19th century historians—the majority of whom were rich white men—depicted ancient people as primitive brutes, it gave the dominant culture permission to subjugate the peoples of Africa, the Americas, and Asia. This historical interpretation is still being used to justify the criminalization of young people of color in Oakland today. That’s why you have to know this history,” I lectured. “If you don’t know how power was constructed or what it’s based on, you won’t have the power to change it.”

Yes, this is how I talked to them. My diatribe was within their zone of proximal development; they understood on many levels. “Discipline problems” were nonexistent. Students became frustrated or angry—they were “normal” preteens—but they were never “defiant.” I never suspended a student and there was no such thing as detention in our school. (We did use “give-back time” and other restorative practices when students violated our community agreements.)

I also challenged my students intellectually. In our decrepit portable classroom under the BART (subway) tracks, I pushed them academically. They complained, and I pushed them some more. They worked harder and harder, I kept pushing them, and they learned and learned and quickly surpassed everyone’s expectations.

I don’t want to simplify this picture. There were numerous visible and invisible structures that allowed me to do what I did and for our students to have the successful outcomes they had. ASCEND was granted a range of autonomies that permitted us to make decisions about curriculum, instructional practices, class size, hiring, and budget. Teachers had a ton of support from coaches, plus regular collaboration time, meaningful professional development, and a strong voice in decision-making. And our staff, students and parents were on the same page when it came to our vision for learning.

ASCEND is my transformation touchstone

I often go back to those first years at ASCEND as a touchstone. My experience as a teacher was completely different from anything before or since. At many moments, ASCEND was a transformed school, a transformational experience, and in many ways we transformed the lives of our students. Having witnessed what a small group of hard working people (working under certain favorable conditions) were able to do, transformation does not seem all that distant and impossible to me now. In fact, it seems very doable. Because of what I experienced at ASCEND, I know we can transform our schools.

There are many more stories to tell about ASCEND (which is still going strong). There are stories of integrated curriculum units, project-based learning and performance tasks that received media attention, impressive test score growth, and even stories of our students graduating from high school and going to college and ultimately becoming teachers.

But where does the story start? For me, as an educator, it started on the first day, when I asked my students to call me by my first name because at the core of a transformed education system lies a whole different set of power relationships.

NEXT: The first year

1 Response

[…] If you have an interest in The Art of Coaching Teachers, be sure to check out the new Education Week blog of that title, authored by California coach Elena Aguilar, a MiddleWeb contributor. Be sure to […]