Supporting History Claims: Post it, Place it, Prove it

A MiddleWeb Blog

The standard to which our students are being held has been raised, even as, in the case of my hard-pressed urban school, the resources with which we are expected to help students meet those standards are being reduced.

This has forced me to take more risks in the classroom, and get creative with how I keep students engaged while at the same time asking them to do something that may be outside their zone of proximal development. What follows is a description of a recent lesson about citing textual evidence that I felt went particularly well.

The Activity

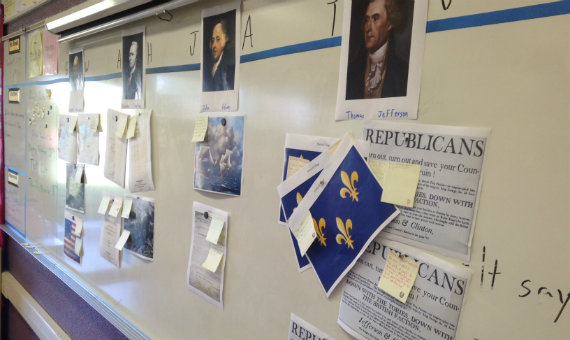

My students are currently learning about the early United States, with a focus on the successes and failures of four American leaders: John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington.

They spent the past two weeks reading and annotating texts about these four men, as well as completing graphic organizers to scaffold reading comprehension and force them to make evidence-based judgments about each leader.

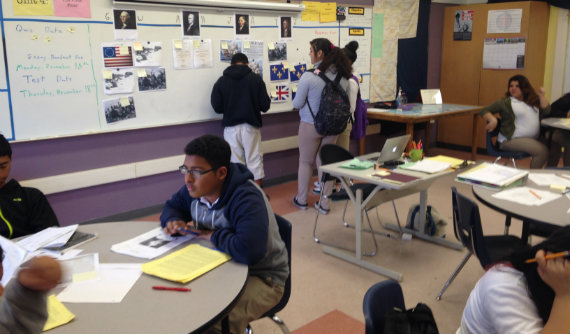

To set up for the activity, I posted pictures of Washington, Adams, Hamilton and Jefferson on one of the white boards. Student groups were provided with sticky notes, a colored pencil (each group had a different color), and an envelope containing four primary sources. Each source could be matched with one or more of the leaders being studied.

I told students to use the texts to determine which leader was the best match for each item, then to write their explanation on a post-it with the colored pencil. After the note was attached to the primary source, the student team would send a representative to the white board to place the primary source near the appropriate leader using a magnet.

Once I determined that there were enough sources on the board, we moved to the next step of the activity. I invited one team at a time to examine the sources placed by their classmates. The team at the board had to choose an item they believed was misplaced or inadequately explained and take it back to their table.

The team was then supposed to use their colored pencil and a new post-it to explain where the source really belonged, or what evidence the other student group should have used to explain their placement of the source. Then one student from the second group would place the source where they believed it was supposed to go, with both sticky notes attached.

To complete the activity, I returned the sources to their original teams. Each team then had to respond to any corrections they received from other teams. If the original team believed they were still right, they had to go back to the text and explain what made their case stronger than the other group.

If a team agreed with the correction, they had to use evidence from the text to explain why it made more sense than their original answer. Students attached the post-its to the final response so that the claim, counter-argument and rebuttal (or agreement) could be seen together.

Rationale

►For many of my students, any amount of reading or writing can be a daunting task. Matching a picture or document with a particular person felt easy, despite the fact that it actually meant they needed to reread large chunks of text. Similarly, although they were only writing one sentence at a time, the net result was easily two paragraphs of writing in complete sentences.

►The second part of the activity was peer review. My students rarely examine the work of their peers, and have very little practice giving constructive feedback. Middle school students are often very sensitive, and this can make it difficult to include peer review in our classrooms. This allowed each team a safe way to give and receive critique, as the only identifying characteristic of the comments was the pencil color.

►The final step forced students to examine their own work more critically. Students who were not clear about particular passages were able to ask me targeted questions, rather than falling back on the ubiquitous phrase “I don’t get it.” Instead, they approached the text as something to be read for comprehension (something that is still not standard practice for the majority of my students).

►Bonus: most students were engaged the entire time. Very few looked bored or completely lost. As there were several viable connections for each source, every team was able to make at least one connection supported by textual evidence.

Many students were genuinely excited to find connections between their sources and a particular person, or to recognize an error made by other students. Some even figured out that the text supported more than one connection for each source, which is an important step in appreciating the nuanced complexity of real historical inquiry.

Final Thoughts

Activities like this do not always go as planned. There is definitely an element of controlled chaos in a classroom that does not center on direct instruction or individual seatwork. However, when lessons like this do work, they address several skills and concepts at once.

More importantly, the responsibility for figuring out and utilizing those skills is placed squarely on the shoulders of the students. The students themselves do most of the teaching, while the teacher gets to watch and learn.

Getting the kids to learn and get the material together on their own is a great way! True the kids get to teach and the teacher watches and learns.

Reversing the roles in the classroom is one of the best ways to maintain empathy for the teachers and the students. Most importantly, a learning environment that is active and invested is much more valuable than one that is static and scripted.

Thank you, Aaron, for that article. That was/is encouraging. And thank you, Joe. That comment of the “active and invested” learning environment is so true. I regularily teach a class of diverse ages and find that I also keep learning the best when we are active and invested. And it is exciting to see the students gain a hunger for learning.

Thanks for sharing, Aaron. Is it possible for you to post the lesson plan and primary source docs online? My kiddos are in the middle of a Constitution DBQ and I am interested in providing this type of activity as a change of pace for our next unit.

I love this- would it be possible to know what primary sources you used? Thanks!