Teaching MS History: Themes or Timelines?

A MiddleWeb Blog

Other students echoed his complaint. What do these dates matter? Why should we need to know the difference between 1789, when the Constitution was ratified, and 1765, when the Stamp Act was passed? Isn’t saying they’re in the 1700s enough?

At this point, after a year and a half of teaching 8th grade U.S. history thematically rather than chronologically, I started wondering whether I was on the right track. If my students weren’t understanding these connections, maybe I was giving short shrift to the momentum of a strong historical narrative.

The power of chronology

Teaching a U.S. history survey course to juniors also left little doubt about the power of chronology. Certain themes, such as reform movements and U.S. intervention in world affairs, appeared over and over. To recognize these patterns was to understand the rhythms of a young country’s experiments at home and abroad.

With a chronological approach, a lot of the work of history happens naturally. This leads to this leads to this, one after the other. Lincoln’s 1858 “House Divided” speech gives way to South Carolina’s secession two-and-a-half years later. China’s artistic Tang Dynasty, contemporaneous with Europe’s early Middle Ages, shines all the more because of its contrast with more militaristic earlier reigns.

I get it. The students get it.

But when I returned to 8th grade U.S. history two years ago (after seven years teaching English), I did not simply want to march through the same material students would encounter again in three years, in the soup-to-nuts survey course they would take as high school juniors.

My thematic approach

My thematic approach

Instead, I wanted to highlight U.S. history’s greatest hits, the moments that most laid the groundwork for today.

Amazingly, my school gave me flexibility to choose the content of the class, as long as there was a reasonable focus on civics and the Constitution.

So, for the past two years, the first semester’s curriculum has covered the following:

- Current events, including how to read and look for news articles;

- The American Revolution, 1763-1783, with a focus on philosophy and primary documents to make it different from many elementary school curriculums;

- A research project on a dictator in another country, to tie in with our focus on governments and to connect with George Orwell’s Animal Farm in English class;

- Federalism in U.S. history, focusing on the conflicts of the 1850s and the early civil rights struggles of the 1950s;

- The Constitution, 1781-1789.

Second semester has been even more thematic. It covers:

- Social reform movements, including women’s history, affirmative action, and Progressive Era reforms;

- A research project on a reformer in American history, including the film “All the President’s Men” to show the power of investigative journalism;

- Civil rights during the Civil War, a short unit centered on the film Glory;

- Total war, using Sherman’s March to the Sea as a springboard, in which we also touch in World War I trench warfare before focusing on the nuclear bomb. In future years, I would like to include 9/11 and its aftermath.

My goal in constructing these units has been to give students a grounding in government, current events, social history, civil rights, and warfare.

And deep questions have easily emerged: What does it look like to be a good citizen? What makes change happen in American history? When should the United States be the world’s police officer?

But we miss a lot

The first year, I didn’t teach John Marshall’s theory of judicial review from Marbury v. Madison, and students’ understanding of the Supreme Court’s power suffered as a result. Had I been teaching the Early Republic chronologically, this topic would have been at the top of the list.

Last year I also realized, as we were finishing the Glory unit, that my students had no idea what Fort Sumter was. Oops! While we had read the pages on social history from the textbook’s Civil War chapter, we had unfortunately skipped exactly how the war started. This year I made sure to discuss the election of 1860 and Lincoln’s decision not to resupply the fort, and my class felt more grounded as a result.

At moments like the Fort Sumter omission, I sometimes despair that I have not taught students enough, that I have left out something crucial. And then I remember: We all leave out something crucial when we teach history. We cannot include every date, every strike, every financial crisis.

National standards lean toward thematic study

Many national standards acknowledge this impossibility by focusing on skills rather than content. The Common Core standards for “literacy in history and social studies” discuss reading and writing literacies, and the National Council for the Social Studies standards cover ten key themes of history.

Even the College Board has jumped on the thematic bandwagon in recent years, with new AP U.S. History course guidelines in 2014-15 and AP European History guidelines in 2015-16 that emphasize historical analysis skills and depth of content more than before.

A swinging pendulum

As the year ends, I do know that the 8th graders in my class need more help realizing the importance of cause and effect. Before our final exam, I plan to remind Danny and the others that the dates I force upon them help illuminate how one event leads to another – just as the events in their lives lead one to the other.

And I’ll hope that this year’s web of history, however scattered, make sense as it relates to the personal identities that these 13- and 14-year olds are forming, as well as to the drumbeat of history that we are all trying to establish.

Images:

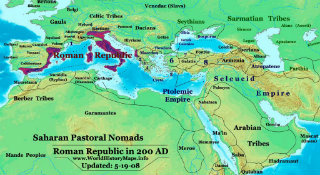

Roman Empire, 200 BC – Thomas Lessman, via Wikimedia Commons

Mesoamerica: via Wikimedia Commons

Great ideas, Sarah. It is a challenge to balance themes and chronology. I think chronology has to play a key role in any history course. But, as you point out, if it’s just one long march from year to year, law to law, war to war, it will be meaningless to students. So you have to use themes AND chronology.

Lauren, I think you’re right that a middle ground is important. As with all teaching, it’s a balance among so many things.

I have this same debate with myself every year when I review my curriculum and think about making revisions. In the last few years, I have tried to get that balance. For example, I teach WWI, then the Russian Revolution, and then WWII, because the chronology makes so much sense! And then I have thematic units in the second semester centered around revolutions, dictatorships, etc. I’m still not sure if I’m making the right choices, though.

Erin, that is so interesting about teaching the Russian Revolution after WWI. I imagine students’ understanding of Russia is deep after having studied the war. Our dictators unit is one of my favorites. I’m not sure there are “right” choices as long as students are engaged and learning specifics about the narrative of history.

This seems to be the consummate challenge for many of us. Realizing that this generation of students can easily retrieve the myriad of facts that make up 8th grade US History, but conversely connecting the dots to the events and understanding the cause and effect phenomenon that reoccurs throughout history is a challenge. My struggle is with student relevancy of the 8th grade curriculum and how it impacts them today. Looking at issues of slavery both during the Antebellum period and the issue of modern day slavery have helped, but finding that marriage between our content and the present is the daily challenge. You article definitely gives food for thought and discussion between high school and intermediate teachers.

Chris, similar to your slavery through line, my students have been fascinated by the history of race relations across the centuries, especially with all the current events this year about police brutality. Relevance for them seems to start when they identify with people – and primary sources – in the past that make them think about their lives today. Thanks for your thoughtful comments.

Thank you for this thoughtful post! Here at CommonLit (www.commonlit.org), we have done a lot of thinking around the benefits of thematic organization for a middle school setting. We hope these resources are useful!

Michelle, what a wonderful site. I love the variety of texts you bring up under various themes. Thanks for posting!

I am inspired by your approach. As I was reading I was picturing the timeline books I love so much. You know the ones that show what was happening in other parts of the world during events happening in the US. Perhaps you and your students could build components of a time line to help the chronological aspects.

Jacqui, what a neat idea about the timeline. I have dreamed about having the students create multiple timelines of different colors – for social, political, economic, and religious history, for example – run all around the walls of the classroom. Now I might be more likely to ask students to use an online timeline creator, such as Tiki-Toki. The simple version on the site (http://www.tiki-toki.com) is free. Thanks for your feedback!

Thank you for bringing this issue up for analysis and discussion. I prefer to teach social studies chronologically but feel that honoring themes within units of study is critical and allows my 8th Graders to deeply understand history and their role in it.

Michelle, “honoring themes” within chronological units sounds like a wonderful road to understanding.

Great post! We seem to have much in common, though I teach 3000 miles away in MA. My curriculum also starts around 1763, my students also read Animal Farm in ELA, and I also struggle with theme/chronology/topic planning.

The good/bad news is that 19th century America is HUGE — so much change in so many ways with so many people! There is a canon of 15-20 items that you gotta include. (Fort Sumter might not even be one of them, but John C Calhoun certainly is.) Beyond that it’s all about historical skills and thinking, with as many interdisciplinary connections as we can for reinforcement.

Thanks for posting!!

Andrew, you are so right about the 1800s being enormous. My students always find riveting those intense photos of John Calhoun and John Brown. How neat that we share so much in common curricularly – thanks for the feedback!

I used to teach US History (11th grade) thematically through PBL in an integrated course (with ELA). The switch from chronological revolutionized the way I thought about my content and my ability to make it feel authentic to my students. After each project along with our standard project reflection we would add to a giant class timeline to help draw new connections and raise new questions. With very careful curriculum mapping we were able to cover our standards but bring so much more meaning to them and as a result I’ve become a passionate advocate for thematic teaching. I enjoyed your article and recognized many of your moments of growth as moments that I had myself. It sounds like you have a very engaging classroom and kudos to you for mixing things up a bit!

What a big impact on your class, and how fabulous that you actually did a giant class timeline! Do you have a photo of it? I would love to see.

Sarah, as a former middle school history teacher (Gr. 7), I too, struggled with this decision. Typically, I went with chronological order, but I think thematic would have been more beneficial due to the importance of social factors in cognition. You might want to check out Matthew Lieberman’s article “Education and the social brain” which elaborates on how human brains are wired to make social connections, especially adolescent brains. I think the dates & locations would carry more weight if they had some sort of interesting social link to them. Some research suggests that the dates or locations covered in class are lost months after the lesson has been taught. I think part of the question is not only what did we miss, but also did we create the conditions for ideas to be retained.

Best of luck!

Dave, what a helpful article for exploring the scientific basis of how social and emotional connections can help memory. The new book “Make It Stick” (Brown, Roediger, McDaniel) also has many helpful tactics to embed learning long-rather than short-term. Are you still in education? Thanks so much.

I am a first year 7th n 8th grade teacher in the Central Valley. Are you on Twitter or Google? I’d love to get a pacing calendar. Our district in central California is doing chronological. I’d love to look at the thematic order u have.

Angella, the calendar looks approximately like this:

Current events: 3 weeks

American Revolution: 4 weeks

Dictators project: 3 weeks

Federalism: 2 weeks

Constitution: 4 weeks

Reform movements: 3 weeks

Reformers research project: 4 weeks

Civil War & civil rights: 4 weeks

Total war: 4 weeks

Good luck with the rest of your first year – you’re almost finished!

I teach 11th grade U.S. History and it is only my 2nd year. The text I use is The Americans and it does have lesson plans for teaching it thematically. I’ve always wanted to try this approach. I like how you balance the importance of chronology with theme to bring in cause and effect as well. Love the timeline ideas above as well. Looking forward to trying these approaches in the future, wherever that may be!

Rachelle, how neat to hear that your text has thematic lesson plans. If you try that approach at some point, I’d love to hear how it goes!

I am interested in your lessons centered the film Glory and All the President’s Men. Would you mind sharing them?

Deborah, the “Glory” unit involves reading a number of Lincoln’s speeches and documents, including the Emancipation Proclamation and the Second Inaugural, before showing the film itself. We also look at a few reviews of books about Robert Gould Shaw, as well as the Augustus Saint-Gaudens frieze on Boston Common of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. The National Park Service has a good site on the memorial. For “All the President’s Men,” I showed it in conjunction with a unit in which students choose an American reformer on which they do a short research paper. We didn’t go much into the details of Nixon and Watergate, using the film more as an example of what serious reporting can accomplish.

Sarah, over the last couple years, the California History-Social Science Project (CHSSP) created a Medieval World unit around this idea of theme, not disconnected locations and dates. It’s free at http://chssp.ucdavis.edu/programs/historyblueprint/sites-of-encounter-in-the-medieval-world-unit. It includes a great interactive map to demonstrate the interconnections of the Medieval World.

Jo, this is a fabulous site! The interactive maps on all topics are fascinating. Thanks for sharing it.

One of my concerns about teaching thematically is that it sounds really cool to those of us who know history and the chronology already. But how is it understood by students who don’t? I am reminded of an anecdote from the history educator Sam Wineburg whose son wasn’t sure if the Korean War happened before World War II or after. It is a perfect example of the importance of chronology. The Korean War, if you understand the slightest thing about it, can ONLY make sense after World War II. It’s not about memorizing dates–it’s about understanding that one could only happen after the other.

But Sarah, I love your calendar. It looks like a good compromise. Wondering when students get the 20th century “half” of US history, though?

Andrew, I am intrigued by 1763 as a starting date for US history course! Try this post which may help a bit with the 19th century: http://ushistoryideas.blogspot.com/2014/11/seneca-falls-womens-movement-and-tying.html

I, too, am always wrestling with what to leave in and what to cut out in order to handle the two competing goals of true student understanding/deep learning while also “getting through it all.” The trick, I think, is best described by James Loewens as thinking about curriculum content as “forests,” “trees” and “twigs.” We need to think about the forests (the major units which could be themes) as we handle chronology and all the trees and twigs – the names, dates and places.

Lauren, thanks so much for sharing your ideas as well as your thoughtful blog post about essential questions that can bring a unit together. I loved Sam Wineburg’s book “Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts” and also his “Reading Like a Historian” site (http://sheg.stanford.edu/rlh).

Has anyone approached Social Studies thematically in elementary?

Diane, I don’t know of any elementary thematic curricula but would be interested to hear from people who do!

This is my grand challenge this summer. I am kind of a blend right now. Teach 8th grade… Pre-Revolution Review, Government, hit a big event every decade, Civil War, Reconstruction. Usually don’t get done with Reconstruction.

Students love the trials, events, experiences they get, but I don’t do well enough connecting it all together, and presently don’t have time to. So I have to find something to connect the “theme” and add in the chronological needed events. They need to understand why something happened and how the events are connected.

I am going to follow this conversation. If any are on Twitter, let’s connect and we can share our journey: @kiplingeric

Eric, this sounds like a fabulous grand challenge for the summer! I’ve found that sometimes the themes of current events can be a launching pad for the themes of history, such as looking at civil rights today to harken back to the Civil War. Good luck!

Thanks for your input and insights, Sarah. I’ve been grappling with this myself, especially as a teacher of language learners. I deeply appreciate your honesty. Balance seems best, but is easier said than done. I often wonder if I’ve connected the info well enough, but then, if I have, I wonder if I’ve done too much of the work for them. Always wondering, always reflecting!

I feel the pull of encouraging students to think like historians, but have also seen (in HS), that foundational knowledge needs constant revision–ideas they learned at one point long ago. Definitely need some facts to be memorized in order to lend touchpoints or starting points for deeper context dives.

Your post also lends credence to the importance and value of teachers being willing and able to share their work with others!

Wendi, you are so right that students sometimes think they know about a historical event, but there are levels of complexity they still need to reach. I love your phrase “deeper context dives,” too. Thanks for the feedback!

Interesting approach.

I reviewed a fascinating presentation for Merlot.org. Try using the approach below, using technology of video

http://mdroots.thinkport.org/

Thanks, Arthur! This looks like very engaging local history for Maryland aficionados.

Sarah

Want to become a Peer Reviewer?

a

Arthur, I’m pretty committed right now a number of other things, but thanks for asking!

I’ve been looking into the idea of teaching 7th grade Social Studies thematically. The focus of my content is North/West Africa, China, Europe, and the Americas from 600-1600 CE, mostly concentrating on movement, migration, trade, expansion. Anyone on here taught that content thematically and have suggestions? This past year I looked at each place from start to finish and then moved to the next, making some connections between each. However I’d like to integrate them more and I think themes would help with that since a lot of their history happened concurrently.