Replace Carrots & Sticks with Restorative Practices

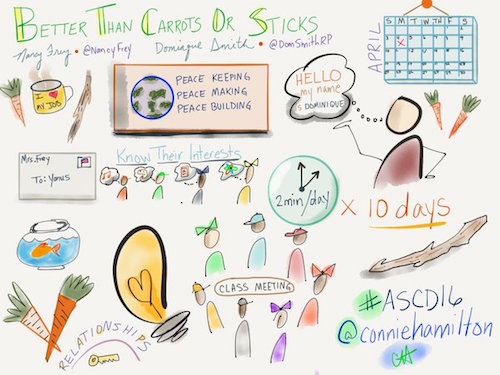

Better Than Carrots or Sticks: Restorative Practices for Positive Classroom Management

By Dominique Smith, Douglas Fisher, and Nancy Frey

ASCD, 2015 (Learn more)

As a literacy coach who frequently works with first year teachers, I was eager to read a book that offered alternatives to rewards and punishments. The table of contents highlighted classroom procedures and expectations, bringing to mind Harry Wong’s practical tips in The First Days of School.

Instead of lists of procedures to post, authors Smith, Fisher and Frey describe what students want from teachers, addressing attitudes, challenges, and sensitivity. Routines and procedures can establish order in the classroom, but the emphasis here is on “the value of establishing relationship-building procedures.”

Students are going to misbehave as they learn and grow—it’s how we respond to their misbehavior that matters. We believe that students should have a chance to learn from their mistakes and to restore any damaged relationships with others.” – Smith, Fisher and Frey

Broken relationships and violated people present daily challenges in our schools. Restorative practices invite teachers to switch their energies from rules to relationships and provide meaningful instruction. How many teachers would volunteer to spend their few minutes of free time sitting behind a sign that says, “How can I help you? I have the time,” making themselves available to students? Such impromptu conversations are investments in relationship building.

Avoiding escalation whenever possible is their best advice to counter overreacting to students who are out of order. Teachers can respond to problematic behavior on a continuum that changes in intensity and severity: simply making eye contact; privately naming the problem to the student; asking the student to name expectations; informing the student of appropriate behavior; physically preventing more problems from occurring.

As essential as positive relationships are, instruction must be purposefully engaging and relevant, too. Teachers who shape lessons with formative assessments, gradual release of responsibility, collaborative learning, AND listening carefully to students are maximizing interactions and influencing students’ academic growth. Teaching empathy and self-regulation impacts the school climate and the academic achievement levels.

An inviting, peaceful classroom culture

Students are quite perceptive about the attitudes of the adults who lead classrooms. Recently, I was quite impatient with students who did not respond attentively to my specially prepared lesson. Reflecting later, I realized I had not considered their mental state before starting.

I had changed their normal procedure and used a very stern, sarcastic voice when I reacted to their questions. I had not acted as an intentionally inviting teacher.

So I was intrigued to read the second half of the book centering on peace. As violence dominates the daily news, teaching students to be peacemakers seems to be critically counterculture. Titles for chapters 4 and 5 struck me as philosophical, so I hoped they also included practical advice on how to teach “Peace Building” and “Peacemaking.” I was not disappointed.

Using restorative practices, the authors note, the community is empowered to resolve problems and not simply focus on the victim and offender. Cultures the world over are characterized by procedures to create peace. Traditionally, schools have dealt with behavioral issues through rewards and punishment, which affect only temporary change in controlling student behavior.

“Rewards and consequences don’t work—or, at least, they don’t teach,” they say. I am guilty of reducing playtime by minutes for misbehavior. Shame and humiliation also fail to produce lasting change. Children have extended this behavior control by bullying, as they follow the model of adults who misuse their power.

A climate that focuses on problem-solving

A climate that focuses on problem-solving

By contrast, setting the stage for positive behaviors, the authors recommend creating a school climate that focuses on teaching problem solving. Three tiers describe:

1) supporting preventative behaviors,

2) designing supports for the few students who misbehave frequently, and

3) describing time-intensive interventions for the few students who exhibit intractable difficulties with behavior.

Restorative practices are built on teaching students how to solve problems, how to be responsible for their own behavior, and how to put themselves in another’s shoes, forgiving each other.

Everyday activities, like developing the vocabulary for discussing differences and solving problems, are integrated into visible curriculum, not hidden or assumed.

Language strongly influences how students feel about themselves, and words are powerful tools to separate the action from the actor. Substituting “I felt…” for “You…” focuses the comment on how the behavior affected others, not the violator’s character. Sitting around a circle minimizes hierarchy, inviting everyone to participate.

Nancy Frey set up a peace table in her classroom, requiring students with conflicts to go there first, providing them with “I” statement sentence stems to write about their feelings before conferencing with the teacher. Expressing their anger in writing can lead students to recognize their own feelings, cool down, own the situation, and move toward forgiveness.

Peacemaking begins at the front door

Creating a welcoming mindset starts at the school’s front door, where the receptionist greets and directs visitors. Even tardy students are greeted, and those who enroll after the school year has begun are given a day to tour, observe, and ask questions, getting oriented to adults and the school climate, before settling into routines.

In setting goals to improve a school, data collected about visits to the nurse’s office, phone calls to parents, interventions, and referrals can complement academic data.

Smith, Fisher, and Frey testify to positive changes they have experienced since actively adopting the mindset of restoration and restitution replacing punishment and consequences. Watching for warning signals of potential trouble, aiming to prevent crises rather than react to them, and cultivating team efforts to build up students empowers teachers who in turn empower students, giving them greater hope for their future.

I recommend teachers and administrators reflect seriously on how to practically apply the message of this book to teach the next generation how to manage conflicts and create peace before they become adults.

Read Chapter 1 of Better Than Carrots or Sticks

Glenda Moyer has served in an English-immersion Christian school in Bogota, Colombia for two decades. After teaching lower elementary student for 15 years, she “graduated” to literacy coach six years ago. Earning her TESOL certificate and teaching SIOP has increased to her sensitivity to ELLs. Her favorite task now is encouraging and supporting younger teachers.

I was wondering if some sample “I” statements can be shared regarding Nancy Frey’s Peace Table.