Beers/Probst: Fake News & Responsible Reading

By Kylene Beers & Robert Probst

Close attention to an author’s words – the responsibility a reader shows to the text – implies and requires a responsibility to oneself as well as the words on the page.

That responsibility consists not only of a willingness to acknowledge and defend one’s own thoughts and values, but to change our thinking when evidence or reason dictates.

A second grader, who read a text about the critical importance of bees in the food chain, adamantly contended, “I don’t like bees because they sting. We don’t need them.” His strong feelings about bees led him to dismiss what he might have learned if he had read more responsibly.

Equally irresponsible is the third grader who read about climate change and responded, “I don’t believe in it. My friend said it isn’t real.” If that child wants to argue with the science presented in the article, that’s one thing. But to dismiss the article because it contradicts what a friend has previously stated is not responsible reading.

Responsibility to Oneself

Our middle grades students are not too young to learn to respect both the words on the page and their own thoughts and values. We seldom have difficulty persuading them to hang on tightly to their own ideas. They come to class, too often, ready to assert that whatever they think, whatever they have come to believe, is flatly, simply, indisputably true and correct.

They are often much more willing to defend their thoughts than to reconsider and perhaps modify them. And they should, of course, defend and protect what is reasoned and defensible. But to hold on to ideas when evidence and reason suggest that a change is sensible is to fail to be responsible to oneself. Somehow, we need to teach them to value change. Not change for change’s sake, but change that results from more information, a richer understanding, a sharpened perspective.

To assert that the text says what it does not say, or that it does not say what it, in fact, does say, is to deny themselves the opportunity to think or to learn.”

They should begin learning, as early as possible, not to misrepresent the text. To do so is to fail in their responsibility to the text, certainly, but even more significantly it is to fail in their responsibility to themselves. To assert that the text says what it does not say, or that it does not say what it, in fact, does say, is to deny themselves the opportunity to think or to learn.

Regardless of their age, students are not too young to learn to defend their position when it is defensible and to change it when new information, insight, or reasoning persuades them.

Responsibility to Others

The apparent increase in what has come to be called “fake news” makes the issue of responsibility to others even more important. It has perhaps always been easy to allow ourselves to be led astray by inaccurate or dishonest texts, especially when our emotions are aroused.

If we find that a text angers us, or, on the other hand, greatly pleases us, then we are likely to react quickly, perhaps without checking to see if either the anger or the pleasure is warranted. Now, however, not only can we be led astray by irresponsible texts, but we have the capacity, through social media, to help that text lead hundreds or thousands of others astray.

The simple act of retweeting or sharing something online can vastly compound and extend the damage.

News: Fake or Real?

We could spend chapters discussing the differences between news that is reported and news that is invented, in parsing the difference between false and fake. We could take up the struggles that social media sites now face as they decide how to avoid promoting fake news without acting as self-appointed censors.

Our right to free speech is a valued freedom in this country, and any group that decides to ban this news or that news because the site is deemed “fake” will face scrutiny. The lines between satire, bias, humor, falsehood, and deceit, and how a text is labeled, will grow blurrier as news sources worry more about high ratings than reliable reporting.

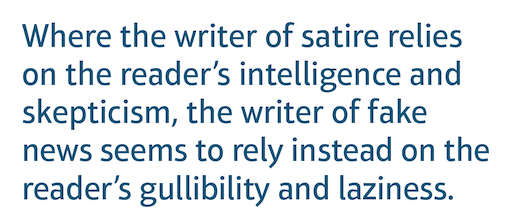

Satire has, of course, been a part of our discourse for a long time, and most of us have probably had the unsettling experience of momentarily being taken in by something in The Onion or by a Borowitz tongue-in-cheek column. There is some satisfaction in seeing through the satirist’s invention to the truth that lies beneath it or behind it. The satirist expects the reader to be sharp enough to see the joke, recognize the exaggeration and invention, laugh at the humor in it all, and not be corrupted or misled by the fictitious elements.

Whatever the writer’s motivations may be, the reader clearly bears the responsibility for avoiding gullibility and laziness. If the reader is taken in by invented news stories, he has obviously failed himself. And if he participates in circulating them, through sharing, reacting, and commenting, then he has failed in his responsibility to others.

Social Media and the News

Responsible reading of the news is more critical now than ever before because so much of the news we all read comes to us from social media sites. In 2016, 62 percent of U.S. adults reported they get at least some of their news from social media, with 18 percent saying all their news comes from social media (Pew Research Center, 2016).

We know there are days when we are part of that 18 percent. We’re fast out the door in the morning, quick into a school with kids or a workshop with teachers, then off to an airplane to do it again the next day in another city. If the plane has an Internet connection, we log on and try to catch up on what’s been happening in the world. Reddit, Facebook, and Twitter become our window to the universe.

We both fell for one of those stories as we wondered just what would happen when that Red Rump Tarantula had her babies, which was the reason the owner gave for posting the warning signs about her throughout a certain area of Brooklyn.

On social media sites, the “news” is quickly disseminated. We may see that 3.5K have shared it, another 1K have commented, and that it’s trending. Surely all those people can’t be duped. This story must be the real thing. The danger in assuming that the story is real means we must put more effort into the reading of news; we must work harder, something that’s tough to do at the end of a long day.

But we can’t look at a news item and presume truth. Instead, we must come to news ready to sort, to cull, to mull, to test, to confirm, to question, to challenge, to discard—and that’s in addition to just reading the content. If we don’t, we find ourselves wondering if that escaped tarantula in Brooklyn could find itself in Texas or Florida. If fake news writers are counting on people to be dumb, then we must be smart. We must muster the stamina to be responsible.

Helping Kids Spot Fake News

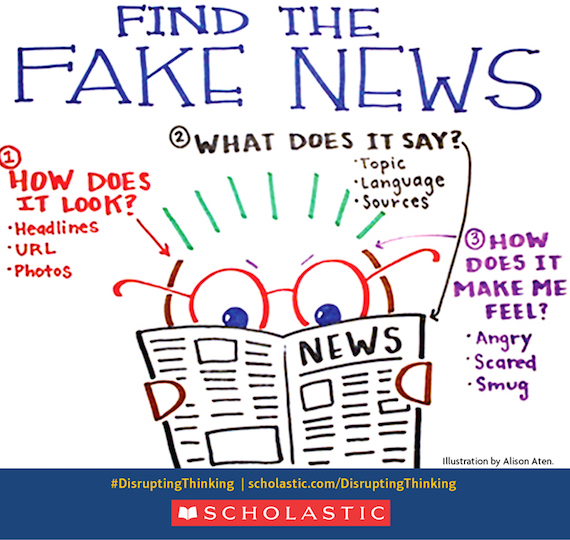

Perhaps rather than wondering which story we should approach skeptically—this one yes, that one no—we might teach our readers to do three things as they look at any news stories, especially when they begin to look at stories online. Let’s teach them to ask themselves:

- How does it look?

- What does it say?

- How does it make me feel?

This anchor chart from our book Disrupting Thinking can help kids keep these 3 Big Questions in mind:

✻ How Does It Look?

When we ask kids to think about how a story looks, we want them checking out the headlines, the photos, and the URL. All caps in headlines, or headlines filled with extreme language, photos that present unlikely information, and URLs that don’t end in .com, .gov, .edu, .org, or .net are worth reconsidering. For example, the URL abcnews.com.co takes us to a source of fake news. That “.co” ending should raise a red flag. A quick search of “how to identify fake URLs” will show you several articles that help you learn to identify fake website addresses.

✻ What Does It Say?

When we ask students to think about what the news story says, we want them to ask themselves questions about the topic, about the language, and about the author. If the topic doesn’t seem credible, it might not be. We should have realized that a story about a lost pregnant tarantula just didn’t seem right. Or if the language is extreme, then there’s probably a problem. And if the author can’t be found or there’s a name but you can’t find out information about the author, think twice before sharing.

✻ How Does It Make You Feel?

Finally, when we ask students to think about how the article makes them feel, we want them to be aware of particular responses: If it makes them excessively angry, scared, or, on the other hand, reaffirmed and smug, then they ought to do some checking before sharing.

When students begin to read news stories wondering how it looks, what it says, and how it makes them feel, we tell them that if any response raises a concern, then the first thing they should do is step away from the share button!

Next, they should look to see if other news sources are reporting the same information. If not, then they should not trust the story. Or, they can head to a source such as Snopes.com to see if the information can be verified.

Until we teach students to read responsibly, we run the risk of being a nation of readers who not only harm themselves, but potentially harm others as they share not just misinformation but blatant lies.

Teacher Turn and Talk

- How much are you influenced by fake news? What’s happening in your school to help teach your students how to critically evaluate news sources?

- Would you say that the spread of fake news is a threat to our democracy?

______________

Kylene is an award-winning educator and the author of When Kids Can’t Read: What Teachers Can Do; Notice and Note: Strategies for Close Reading; Elements of Literature, and many other books. In 2008-2009, she served as President of the National Council of Teachers of English and was the editor of the national literacy journal Voices from the Middle. Most recently Kylene served as the Senior Reading Advisor to the Reading and Writing Project at Teachers College, Columbia University.

Robert is an author and consultant to schools nationally and internationally. He speaks to administrators and teachers on literacy improvement, particularly issues surrounding struggling readers and meeting standards. Bob is Professor Emeritus of English Education at Georgia State University and has served as a research fellow for Florida International University. He co-authored Notice and Note with Kylene.

The article is excerpted from Disrupting Thinking: Why How We Read Matters by Kylene Beers and Robert E. Probst and reprinted with permission from Scholastic.