How We Refer to Groups of People Matters a Lot

A MiddleWeb Blog

Names matter. A lot.

This post, however, is not about students’ names, but about the names we use for different groups of people. My first unit of the school year is on the American West after the Civil War. The wars between the United States and Native Americans is at the center of this unit, so one of the first things I feel a need to address with students is the names we use: Native American or American Indian?

Clearly, when discussing specific battles, I use the name of the tribe. But even this gets complicated. And sometimes, it doesn’t make sense to use tribal names. For example, if you are talking about white American attitudes towards native peoples in general, it makes less sense to talk about the Lakota Sioux because white Americans were more likely to generalize about all “Indians” than to make tribal distinctions.

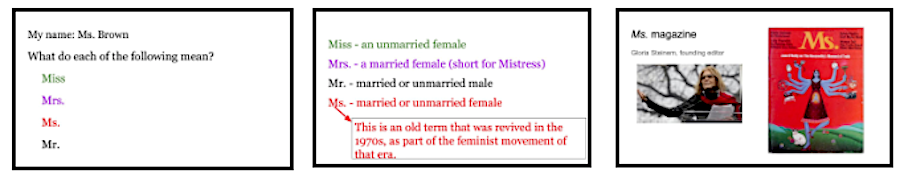

So one of the lessons I teach early in the year centers on a discussion of why names are so complicated. The first thing I do is tell them about my own name: Ms. Brown. I have found that students really have no clue about the differences between Miss, Ms. and Mrs., so I start with that, using the slides below which explain the meanings of each and the revival of “Ms.” as part of the 1970s feminist movement.

This gives me the opportunity to explain that I am a feminist. Middle schoolers are wrestling with identity and their sexuality. Girls in particular have a lot to grapple with in this #MeToo era. Describing myself as a feminist sends powerful messages to all students. In recent years, I have had several transgender and gender non-conforming students, so I also take a moment to point out that we are perhaps in need of new prefixes.

Naming: historical trends

All of this is my introduction to a reading about the use of Native American versus American Indian. We discuss the reading at length. Below are a few of the questions that guide the discussion.

- Why have names and descriptors changed over time?

- What do the names tell us about the historic moment in which they were created? What factors lead to changes? Who tends to make the changes, the group itself or others? Why might that be relevant? Or isn’t it?

- What do names tell us about the power dynamic between different groups of people, and how those dynamics have changed over time?

- How/why do some names become offensive, pejorative or just not socially acceptable? How do we account for the fact that not all people of a group agree about the use of particular names? Who in society gets to “decide” the use of one term over another?

- There is greater visibility today about the significance of “whiteness.” How does this impact what we call Americans who are not people of color?

- What is the relationship between race and ethnicity?

These questions are only a starting point, and by now you can probably see how complex this one short reading can be.

We also discuss what we should call non-Indian Americans. In the late nineteenth century, Native Americans would use the term, “white man,” which is curious, I tell students, because at least some of the soldiers who fought against them were actually African American. But for the Indian, they were all “the white men.”

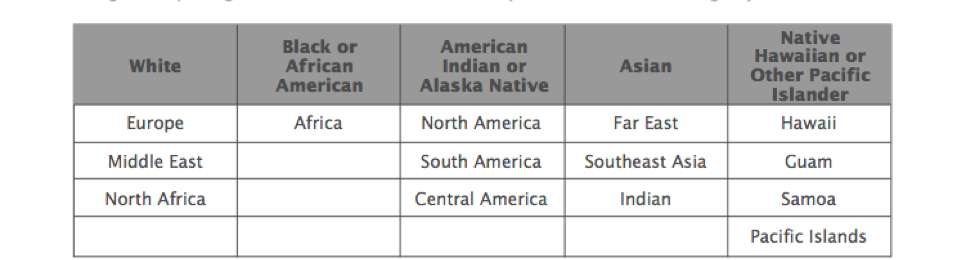

This leads the discussion to the use of the terms Black versus African American. I like to use the U.S. Census as a way to get at the changing notions of race and ethnicity in the United States. The table below, from the Census Bureau, shows the current racial categories and their geographic origins (Hispanic is considered an ethnicity, and Hispanics can either be white or Black).

Click to enlarge. Source: https://www.census.gov/mso/www/training/pdf/race-ethnicity-onepager.pdf

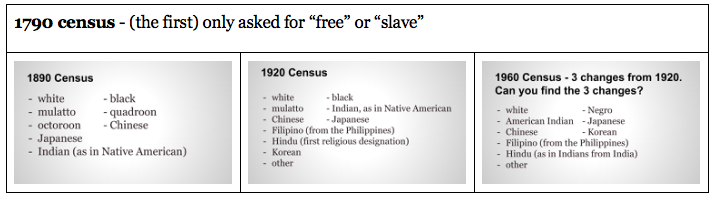

Students are mostly familiar with these basic five, though they are often confused about the Hispanic designation being separate from race. It is important that students understand that there is nothing “scientific” about these five. They merely represent the historic/social context of the United States. They may appreciate this better by looking at earlier census categories. The U.S. Census published an interactive visualization in 2015 that gives the full picture. Or it can be simplified for students, as I have in the chart below.

At some point, usually later in the year, we also discuss capitalization of Black and white. It is too complicated to discuss in this blog post, but see sources below for help with this.

During our discussion, someone, usually a white student, wonders aloud whether it is more appropriate for whites to use the term African American instead of Black. My Black students usually differ in their opinions on this point.

At this point, some students appear uncomfortable with the discussion. And that is the moment when I stop to point out that these topics are uncomfortable, but the only way we can ever deal with concerns about what is racist to say and what is not is to address the concerns. This year, for the first time, I will also bring up the relatively new term “Latinx” to refer to Latinos and Latinas.

Why teach this?

This lesson serves two important purposes. It first addresses the immediate concern over the use of the terms Native American vs. American Indian, so I can go on with our unit on the West. But more importantly, it begins to develop a classroom climate where students can feel comfortable discussing complicated and controversial topics.

I conclude our discussion by explaining that names are complicated because history is complicated. Names and words matter because they have the power to offend. These particular names are related to our past history of racism, colonialism, discrimination and slavery. I remind them that this discussion is just a beginning toward understanding this disturbing history.

The use of the n-word is really an entire separate lesson, but be aware that the topic might come up. The 2013 opinion piece, “In Defense of a Loaded Word,” by Ta-Nehisi Coates is a useful starting place (for the teacher; probably not appropriate for middle schoolers) to thinking about this topic. I highly recommend reading the (many) comments; they will give you ideas for guiding a thoughtful discussion of this sensitive topic. There are a few other sources listed at the end of this post.

Most importantly, if this post has you nervous, wondering about whether it is even a good idea to bring up such touchy subjects in the first place, I cannot recommend strongly enough listening to episode #4 of the podcast “Teaching Hard History” from Teaching Tolerance.

In this podcast Professor Steven Thurston Oliver eloquently explains the importance of this kind of teaching. He reminds us that our students already have been exposed to these topics and questions; they’re in the air we breathe. So if we don’t discuss them in class, students will wonder about them in some ignorance.

These discussions can go a long way to engendering trust, Oliver explains. By bringing these issues up, you let students know that your class is about serious topics that matter to them. And what better way to begin the school year?

Resources

► U.S. census quick facts on race

► Helpful overview of census and “5 races”

► Overview article on census interactive (but use the links in the post above for the actual visualization, as the links in this article are now broken).

► Teaching Tolerance, “Straight talk about the N-Word”

► Scene on Radio podcast’s “Seeing White” series

► Facing History, “Addressing Dehumanizing Language from History”

► NY Times opinion piece on using capital B for Black

► Blog post by the “Radical Copy Editor” on use of capitalization for Black

► Huffington Post, “Why People are Using the Term Latinx”

► Remezcla, “Latino vs Hispanic vs Latinx: A Brief History of How These Words Originated”

► Defining Aboriginal Peoples in Canada (International Journal of Indigenous Health)

Added 6/24/20:

► “AP style is now to capitalize Black and Indigenous” (Nieman Lab)

Lauren, thank you for this deeply thoughtful article, as well as the many complex resources you have shared. I know I will be returning to the piece in the future. Good luck with a new school year!

Thanks, Sarah. Best of luck to you as well!

How about “First Nations” instead of “Native American” and “Inuit” in place of “Eskimo?”

Thanks, Ken. I don’t know why, but “First Nations” seems to be used in Canada and not as widely recognized in the U.S., though Inuit does seem to be recognized.

Regarding Ken’s comment, in a discussion on Debbie Reese’s blog, American Indians in Children’s Literature, regarding Indian vs. Native American, she related that different folks prefer each, but that the term “tribes” is actually incorrect and that if we really want to be precise, we should be using the term Native Nations. I actually prefer that term, especially since reservations are legally associated with their native “nation.”

Barbara, this is a good point and reminds us of how many things we need to consider regarding our language. Words like “tribes” and “huts” and “native dress” suggest primitiveness about groups of people and should be avoided. We don’t refer to the French, the Dutch or other Europeans as tribes.

Similarly, we should be careful when talking about Africa and African nations. This is complex due to the history of Africa and the creation of many nations as part of the 1884 Berlin Conference, which is when European colonial powers carved up Africa.

Another linguistic change I am noticing today is the use of “enslaved” instead of “slaves.” While reading this Sunday’s New York Times magazine on the 1619 Project, I decided to go back and look at some of the posts I did on my U.S. History Ideas blog about slavery, and while fixing a few broken links in this post: http://ushistoryideas.blogspot.com/2014/10/teaching-about-slavery-before-missouri.html, I realized that the only change in the html address was the use of “enslaved” versus “slave.” Check out this blogpost: https://pastexplore.wordpress.com/2015/07/10/the-paradoxical-nature-of-the-enslaved-person-vs-slave-name-debate/ for a thoughtful discussion of the use of the two terms.

I am planning to incorporate this lesson plan and comments with my What Do Sociologists Do Introduction talk. I am using 50 Years Since….. as my overarching theme for the semesters this academic year. Fits so perfectly with contemporary fear and hate as with Vietnam War, the murders of Martin and Bobby and how words in songs became the anthems for Peace, Freedom, Love etc. Words are the necessary symbols for communication…..I want students to explore this notion as they develop their Sociological Imaginations. I will use blog responses as well. I generally have a future social studies teacher in my mix and I like to model strategies for teaching. Thank you all for marvelous information! God bless you all and success to all of our students!

Thank you so much for your comment! I’m glad you found it helpful. Hope it goes well with your students. I like the theme, “50 years since…”

Thanks to Sarah Cooper for alerting me to the continuation of the debate about capitalizing “Black” and “White.” Again, complicated because the history is complicated.

“AP style is now to capitalize Black and Indigenous” (Nieman Lab)