Teach Students to Build Up Ideas with Dialogue

Frequent, high-quality classroom conversations make a huge difference in how far middle grades students advance academically, socially and emotionally.

The benefits of conversing with others (especially in pairs) include helping students to clarify complex concepts, developing academic language, fostering feelings of agency, and strengthening relationships with classmates.

A high quality conversation is a respectful interaction in which participants take turns to build up one or more ideas using a handful of academic conversation skills. I italicized ‘build up one or more ideas’ because when students don’t enter into a conversation ready and willing to collaborate in the idea-building process, then the conversation tends to be short and shallow.

Students need to identify as “idea builders”

A cornerstone for high quality conversation is developing a learning culture based on what I call an idea-building mindset. This is the conviction that learning stems from using skills and knowledge (facts) to build up claims and concepts rather than just accumulating skills and knowledge for doing well on tests.

Both teacher and student need to have this mindset. When they do, they foster a classroom culture that is grounded in the co-construction of ideas. In every subject everything they do is used to build up ideas of value.

Unfortunately, by the time many students get to the middle grades, they have the mindset that the goal of learning is the accumulation of extrinsic rewards. To change this perspective, it is imperative to emphasize, all year, that in this classroom (school, district) we learn through building and co-building up ideas with others.

Four skills help students build up ideas

There are five main skills used in effective conversations, four of which are used to build up ideas. The first skill is knowing what’s already strong, what’s still needed, what’s helpful and what’s not helpful.

For example, if you and I are conversing and you say, “Animals have adapted to avoid being eaten by predators,” and I say, “Yeah, I agree,” you would employ your idea-building skill by saying something like, “We need to come up with examples of that statement to build it up. And we could clarify the terms adapted and predators.”

The second skill is posing and choosing the most relevant and buildable idea that will both motivate students and help them learn what they need to learn. With the class you can practice posing a wide variety of ideas with more and less potential and talk about which ones are better for a conversation. This is a very helpful life skill, too.

Skills 3 and 4 are clarifying and supporting, which are the two main skills needed for building up ideas. Students can clarify by asking questions, asking for elaboration, defining terms, and paraphrasing. Students can support ideas by including evidence, examples, reasoning, adding details, and/or explanations.

In fact, standards that focus on supporting ideas with evidence, etc. have been around for a long time, but many students just think of this a requirement for points (and mostly in writing) and not as a vital way to construct lasting ideas in their minds. So the more we can emphasize that students are in school to build up important ideas that they will use and keep adding to during their entire lives, the better.

Applying the first 4 skills

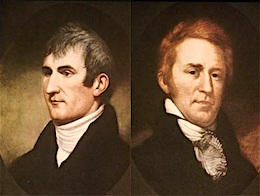

Look for the use of these four skills in the following actual conversation between two students, prompted by the question, “Do you think Lewis and Clark were a good team to lead their expedition?”

A: I think they were a good team.

B: Why?

A: Cuz Clark, he knows about nature and can make the boat. Lewis looks like the doctor and…

B: And Clark knows everything about plants.

A: How does that help?

B: They would have to eat some plants and not eat the poison ones. Maybe they had to find them for medicine, too. I don’t know.

A: And the other guy knows about other things.

B: You mean Lewis?

A: Yeah.

B: What other things?

A: Maybe like he can read maps.

B: Did they have maps?

A: I don’t think the whole trip, but maybe…

B: The first part of it, yeah.

A: So maybe he knows how to make maps.

B: I agree. So I think they were a good team, too.

Even though this dialogue could be improved (as most could), notice how the two students used the skills of clarifying (“How does that help?” and “Did they have maps?”), and supporting (“he knows about nature and can make the boat” and “maybe he knows how to make maps”) to build up the idea that Lewis and Clark were a good team.

Also notice that students were allowed to (a) decide between two options and (b) use (not just memorize) what they had learned about the expedition’s events and people involved. (The expedition famously included Sacagawea and also Clark’s slave York; their roles during the expedition would be another example of an idea-building conversation.)

Skill 5: Evaluating the weight of the evidence

Many conversations are arguments. An argument exists when there are two or more opposing ideas and there is a need to choose one over the others.

Rather than the all-too-common competitive argumentation that students often see at home and in the news and social media, I encourage students to engage in collaborative argumentation, which focuses on having all participants build up all ideas as much as possible before deciding.

Students in middle grades like to argue, to be sure. Yet we need to focus this energy away from winning at all costs and toward building up the truth. There are too many arguments in which a student with bully-esque tendencies chooses one side beforehand and works hard to make sure the opposing side is built up as little as possible.

How do we build these skills?

There are several ways to set students up for success in using the above skills. One way is to make sure students have enough content to talk about. This content might come from reading, watching, class discussions, images, home interactions, social media, etc.

The second way is to make sure students have different pieces of information to contribute. If they all have the same information, they won’t need to push themselves to clarify it for others or to listen actively. But when they do have different information (e.g., they have read different texts on a topic), they are more likely to push themselves to clearly articulate thoughts and ask for clarification and support – especially when they are motivated to co-build up an idea.

We also need to cultivate nonverbal skills – body language. These include eye contact, head nods, posture, and gestures. I also include prosody in this category, which includes how students use intonation, stress, volume, pitch, etc., while using language to communicate thoughts (i.e., not sounding like a robot).

In order to build up these conversation skills, it is vital to provide more opportunities and time for conversations. Teachers should think about ways a conversation might help in the beginning, middle, and/or end of every lesson. Think about how conversations can help students share with each other to clarify terms, develop language, build up concepts, and connect with others. And think about the powerful opportunities that conversations offer you for formative assessment.

Conversation skills are not just for conversations

Teachers can and should weave these vital skills into the wide array of lesson activities that emphasize reading, writing, listening, and speaking.

For example, as students are sharing their writing with peers have them critique the quality of the text by asking clarifying and supportive questions (e.g., What idea are you trying to build up in your readers? Do you have better evidence than this? Can you clarify the term ____?). And in activities such as pair-shares, jigsaws, gallery walks, and peer editing, you can require students to ask these types of questions when they are listening to peers.

The middle grades are prime time not only for developing conversation skills but also for using conversations to help students learn and grow into the amazing people they are meant to become. When students enter into conversations ready and willing to use their conversation skills to co-build up important ideas, their conversations and their learning will reach new heights.

Jeff has taught in diverse elementary and secondary schools and has worked as an instructional coach in urban school settings. In his current research and professional development work he collaborates with teachers to learn what works best in real classrooms to help students learn through rich interactions and conversations.