Meeting the Needs of SLIFE in the Middle

A MiddleWeb Blog

I drive them crazy with my high expectations, but I make sure not to order them to do their duties. Instead, we do them together.

I explain that Vietnamese children are expected to contribute to the maintenance of the house. And so we spend time washing dishes, folding clothes, and setting and clearing the table after meals. An outsider can tell that our Vietnamese culture values community engagement. We do things to keep the community functioning.

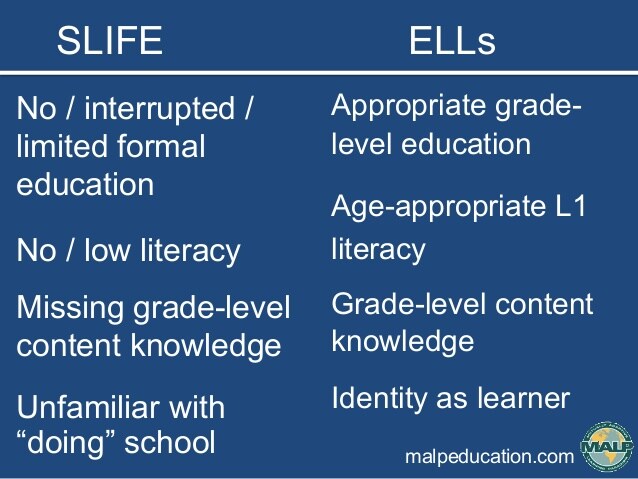

Likewise, when we look at our schools, we can see that our expectations for how students will learn is all culturally rooted too. And unfortunately, the way a school functions might be at odds with what students with limited or interrupted formal education (SLIFE) are familiar with.

In Dr. Helaine Marshall’s book Meeting the Needs of SLIFE (DeCapua et al., 2020) and in our podcast conversation, she suggests not teaching SLIFE the way we want them to learn but teaching them the way they learn best.

It’s not that SLIFE lack a strong emphasis on literacy or academics in their cultures but that these things look, sound, and feel different in them.

We need to take these cultural differences into account and shape instruction that is more culturally aligned to what SLIFE are familiar with. This accommodation paves the way to the smooth landing students need when learning in a new culture.

Formal Education: How we teach

Learning in many western countries is a formal experience. It’s so natural to most of us that we don’t even think about it. Many of us have grown up in this type of formalized learning, immersed in it from primary school to university.

The features of formal education are:

- learning with same-age cohorts

- individual accountability

- literacy-focused education (learning through printed text and by producing writing)

- academic ways of thinking (e.g., categorization, evaluation, labeling, comparing)

- decontextualized texts (tasks not relevant to the daily functions of life) [DeCapua et al., 2020]

For example, a task in formal education might be to conduct research on one of the European explorers in the 15th century and write a report or give a presentation on them. Learning about people 500 years ago is decontextualized because it is not directly relevant to people’s daily lives in the 21st century. Researching and writing are solitary activities and the report or presentation produced does not contribute to the community directly.

There is nothing “wrong” with this model. The challenge occurs when this model is not familiar to many SLIFE as their learning follows a more informal model. Let’s shift to what that model looks like.

Informal Education: How SLIFE learn best

About 70% of SLIFE come from collectivist cultures (DeCapua et al., 2020). These cultures place tremendous weight on relationships. Learning for SLIFE is not transactional but relational; it’s not about completing decontextualized, individual tasks but about providing a service to the community that benefits all immediately.

- collectivism

- oral transmission for learning

- informal learning (i.e., learning a skill from people you already know and applying it immediately to contribute to the community)

A typical task in the informal education model might be learning how to arrange the altar for a celebration. The children are responsible for learning what items the altar must have and where to place them. An older sibling or grandparent who lives in the house might teach them what to do.

Their work is essential because it contributes to celebration as guests will come and pay their respects to the altar when they arrive at the house. The children learned this task, and by completing it, play a central and immediate role in celebration.

This informal model is drastically different from the formal one, and these differences present significant adjustment challenges for SLIFE. What appears as an achievement gap is really two cultures seeing the world through different lenses.

Meeting in the middle

Luckily, we can help SLIFE connect to and learn from a more formal style without forcing them to sink or swim. We can bring the literacy focus from formal education and the relational learning from the informal model together to meet their needs.

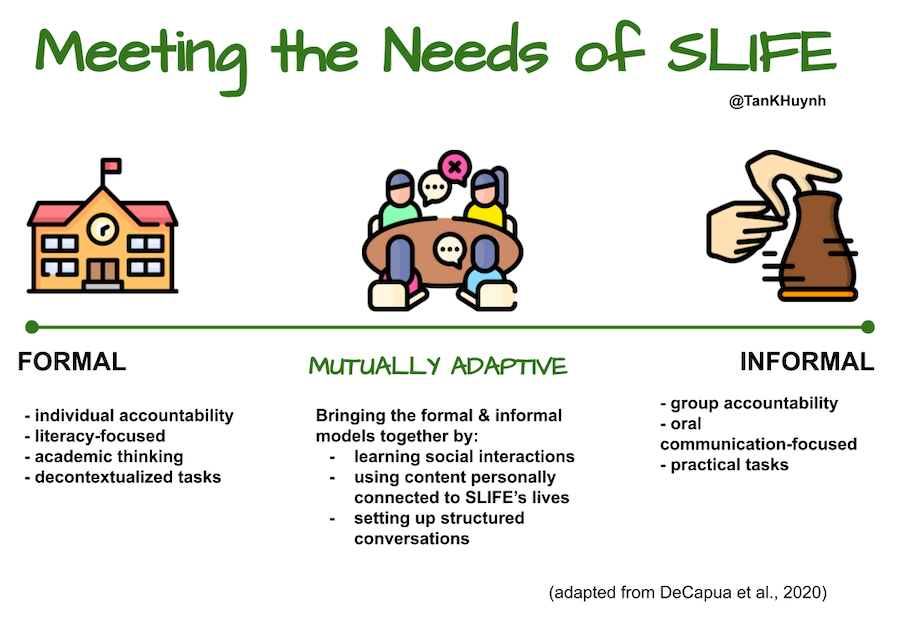

Dr. Marshall and her colleagues have created a framework called the Mutually Adaptive Learning Paradigm (MALP). This model is selective in combining elements from formal and informal learning approaches to maximize the success of SLIFE in the classroom.

For MALP to be effective, though, there are two conditions for learning. Teachers must:

- create learning experiences that foster interconnectedness, and

- set a context for the content that makes learning personally relevant.

By definition, a SLIFE learner has experienced an interruption in their learning. With sincere good intentions, most educators will rush to teach them – but in the formal, standards-based way. However, content must be taught as a relationship experience to connect to this vulnerable subset.

Group work, in particular, is where interconnectedness has a chance to grow, and learning about how the content shows up in students’ lives makes it personally relevant.

SLIFE learners are used to learning practical skills that are immediately used to contribute to their communities. Therefore, they need to see in their new classrooms how they can apply the new content and skills in their lives.

In the MALP model, some processes also align with the way SLIFE prefer to learn. These processes include:

- using oral language to scaffold written work, and

- incorporating shared experiences with traditional individual accountability

A lesson that encapsulates these processes might be a shared video-watching or reading activity. After the students are placed into groups, they have to process the resource with their partner. As they read a text or watch a video, they pause periodically to talk about the section they just viewed. They take turns writing down notes on a shared document.

This lesson uses oral language to scaffold reading, viewing, and writing. It also gives students an opportunity to practice having individual accountability by taking turns to write.

Closing thought

Are Dr. Helaine Marshall and her co-authors suggesting that we do away with reports, presentations, or writing and reading? No, their suggestion is to meet SLIFE learners in the middle, where elements familiar from their learning cultures are integrated with elements of the school learning culture we are inviting them to join.

It’s in this middle space that we create something new that resembles pieces of both cultures. It’s in this fertile space where SLIFE maintain their connections to their cultures and languages.

Reference

DeCapua, A., Marshall, H. W., & Tang, F. (2020). Meeting the needs of SLIFE : A guide for educators (2nd ed.). University Of Michigan Press ELT.