A Joyous Vision of the Holodeck Classroom

From the Campfire to the Holodeck: Creating Engaging and Powerful 21st Century Learning Environments

By David Thornburg

(Jossey-Bass, 2014 – Learn more)

In my history classroom, eighth graders find an 1863 newspaper article about Gettysburg in an online database, enter citation data into a research program for an annotated bibliography, and check the morning’s headlines on their smartphones. I appreciate educational technology but am nowhere close to its bleeding edge.

However, it soon became clear that this book is not simply about technology but about good teaching, particularly project-based learning: “how to make the adventure of learning joyous for all,” as its engineer author proposes.

Learning: The next generation

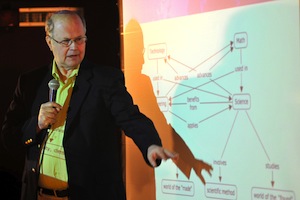

Thornburg’s guiding concept builds on his 1996 book Campfires in Cyberspace, in which he laid out four “primordial learning spaces”:

- The Campfire: the traditional lecture or storytelling style of teaching;

- The Watering Hole: the social learning that happens when we discuss concepts with each other;

- The Cave: the quiet reflection we do on our own;

- Life: the application and transfer of knowledge.

Chapters on each of these metaphors remind teachers to go beyond front-of-the-class instruction and even beyond collaborative work. For instance, referring to the individualistic Cave space, Thornburg says that “educators need to realize that this kind of reflective thought is essential to the problem-solving process and to build it into the school day.”

An interlude chapter on “The Challenge of Technology” explains one of Thornburg’s main themes: that we should not use technology simply to “replicate” what we’ve always done, “amplifying strategies that have never worked for all learners but implementing them with new technology.” For instance, interactive whiteboards still keep the focus on the front of the room, and clickers still rely on multiple-choice thought.

Instead, Thornburg argues, “we should use the new tools to do different things, not just to do old things differently.”

Looking for the hard fun

The next four chapters treat the four learning spaces technologically, and I found them progressively more exciting as Thornburg included more examples with each one.

“Technological Campfires” explores how to generate questions that lead to a culminating project and how to make introductory videos to hook students.

“Technological Watering Holes” covers texting, Edmodo, and asynchronous online conversations, and it reminds us that well-designed projects can help with differentiation among learners.

The “Technological Caves” chapter calls computer programming “a creative and reflective discipline.” The 1980s program Logo is still around, functioning like a linguistic version of the more recent and pictorial Scratch.

Thornburg tells a story of a student who described Logo as “fun” and “hard” – the difficulty made it fun. Ever since, the concept of “hard fun” has guided the way Thornburg sees the intersection between challenge and play. Earlier in the book, he suggests that Lev Vygotsky’s idea of the zone of proximal development, combined with Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s notion of flow, can help us find the right challenge for each child.

In the chapter on “Technological Life Spaces,” Thornburg touches on Arduinos, 3D printers, Sketchup, and a myriad of other apps and sites for robotics and building. In the process, he gives as robust an argument for the Maker movement as I’ve seen.

A parent who helped with our school’s robotics club says she originally pointed her son toward robotics partly because she didn’t want him just staring at a screen. Thornburg echoes this shift from screens to hands-on activity: “The dot-com world has morphed into the world of fabrication, and our students need to be as comfortable working with the new tools as previous generations were with the old ones.”

Inside the holodeck

Throughout the book, Thornburg discusses not only the value of tactile learning but also the importance of physical spaces in schools, such as a reading teacher’s dream classroom that would feature a “tumbling mat in the center with nice cushions for those children who like to read lying down.”

The final chapter merges space and pedagogy in a natural culmination of the book. Thornburg describes his concept of the “educational holodeck,” a nod to Star Trek: The Next Generation. It is a “windowless and rectangular” room, with enough seats for twenty or more students, featuring screens on the walls that serve as “viewports.” In such a space, perhaps a dedicated and converted classroom, students embark on a “mission” that feels real, such as traveling to Mars as a group of scientists and facing risks along the way.

Not every school will be able to build such a room, he acknowledges, but everyone can adapt elements of this “immersive” and “interactive” experience for their own classroom. You can see a brief overview of the holodeck Thornburg and his wife have created in Brazil through a useful five-minute video on Edutopia.

From the Campfire to the Holodeck is filled with such middle school practices as hands-on learning, student-generated questions and self-directed research. It reminded me once again that middle school often requires the best teaching because we must be especially engaging and relevant to keep our students’ attention.

It would be difficult for anyone reading this book to return to the classroom without feeling invigorated and thinking about two questions:

► First, how am I moving my students from the Campfire to the Watering Hole to the Cave to Life?

►Second, how can I make my own projects ones that students remember not just for the test, not just for the end-of-unit assessment, but for their entire lives?

Sarah Cooper teaches eighth-grade U.S. history and is co-dean of faculty at Flintridge Preparatory School in La Canada, California. She lives just outside Los Angeles with her husband and two sons, who sometimes sit at the dining room table tinkering with an Arduino board. She is the author of Making History Mine (Stenhouse, 2009). Read this excerpt at MiddleWeb.