8 Ways to Make MS History More Meaningful

At the end of every year, like so many history teachers, I regret simply skimming the surface of the past. Three weeks, and there went India.We spent half a day on Emperor Ashoka, and I completely glossed over the Mauryan Empire.

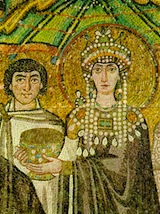

Should I have devoted more time to Andrew Jackson and less to Abraham Lincoln? And how can my students possibly go through their teenage years, let alone adulthood, without fully processing the achievements of women such as Jane Addams and Hildegard of Bingen?

I think I’ve perfected the “oh well” half smile and apologetic shoulder shrug in response to my students’ desire to dive deeper into history.

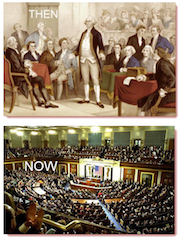

Another year, in an eighth-grade U.S. history class, Gianna asks, “How does Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party relate to politics today?”

What a great question – and what a thoughtful invitation to veer from my lesson plan on Hamilton and Jefferson. My students need to know the history of American political parties, but they also need to make relevant connections to contemporary issues.

Our weekly current events discussions only hint at the intricacies of today’s government. Could I squeeze in a modern-day political debate at the end of the Early Republic unit?

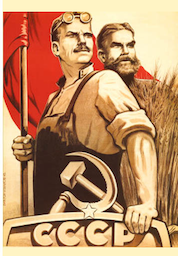

As we discuss modern political systems in a seventh-grade global cultures class, Camilla wonders why Communism was so appealing, anyway. This I can answer succinctly – “Wouldn’t you like everything to be equal, at least in theory?” – before moving back to our conversation comparing capitalism, Communism, and fascism.

The bane of the history teacher’s existence is coverage. The middle grades social studies curriculum is invariably a mile wide and an inch deep, making it difficult to do justice to the subject and to our students. So we trudge on, moving like exhausted soldiers determined to keep up with the general’s plan for advancement.

We are dedicated, but many of us wonder if there is a better way. Can we tap into our students’ curiosity about the world around them without dulling their senses through content overload? Can we probe more of the mysteries and miseries of global cultures and still prime our students’ passion for activism and their hope for the future? Yes, we can. The solution, I believe, lies in the search for meaning through personal connections to history.

Goals: Finding a personal connection

Four years into teaching middle school world and U.S. history, influenced by the ideas of Understanding by Design (Wiggins and McTighe 2001), I started asking myself at the beginning of a chapter: what do I want my students to know and be able to do with this information? Such a big-picture approach helped me create more meaningful assignments that generated measurable knowledge. Instead of just putting together interesting bits of material, I began to understand how to visualize the beginning, middle, and end of a unit.

After several years of these small steps, I felt comfortable expanding this emphasis on specific goals to an entire course, asking myself two guiding questions: (1) who are my students now? and (2) what do they need to learn to become conscientious and knowledgeable adults?

Our students are middle schoolers

Passionate people, they want to harness their enthusiasm to change the world for the better. They crave movement and physical expressions of learning. Joyful and humorous human beings, they pride themselves on seeing the fun in most any situation. Like all of us, they want to feel appreciated and competent and useful. The history we teach reaches them best when it involves novelty, humor, meaning, a sense of self, and a connection to the real world.

History students need symphonic skills

The vast majority of our students will not become professional historians. In their careers, however, they will need to know how to find valid information, analyze it from multiple perspectives, and communicate it clearly. In a world that New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman has famously reminded us is increasingly “flat” (Friedman 2006), our students also will need to distinguish themselves with creative approaches and critical thinking.

When working with students who may not immediately see the value in becoming historians, how can we guide them toward exciting discoveries and meaningful relationships while still focusing on academic standards and curricular mandates? The best answer I’ve found is to teach under the shelter of broad themes and global concepts, conveying ideas that connect content across topics and grade levels.

With this approach, students are not focusing on the tiny details of history, although facts remain crucial to effective argumentation. Instead, adolescents see history through the eyes of individuals and then move outward to larger implications and patterns. One of the best places to begin is with the personal, for who isn’t interested in learning why and how we have come to live as we do?

Goals for Middle School History

All of my teaching is rooted in state and national standards. Here I want to emphasize the larger goals of teaching middle school history, which bring the standards to life.

1. The Role of the Individual: Assessing Who Makes History

I begin my history classes each year by telling students, “You will all make history.” Focusing on notable individuals of the past helps students envision how they, too, can influence the future and use their burgeoning power effectively. Such strategies personalize the content.

2. How Opinions Become History: Analyzing Point of View

3. Fighting Words: Examining Rhetoric, Reasoning, and the Role of Language

History comes alive most vividly through the words of people who lived it. Writing is a source of inspiration and power. By inspecting speeches, letters, and diaries, students can explore the power of literature to move people—not to mention their own ability to effect change through a letter to the editor or a political poster. Fictional sources also can engage students’ emotions and encourage intuitive leaps.

4. A Broader View: Finding Patterns in the Past

5. How Historians Think: Writing as a Way of Understanding

Students can examine and further understand what they think about history by pulling together their ideas into analytical paragraphs and essays. Such high-level synthesis goes to the core of what real historians do: examine primary sources and make a case for a point of view.

6. Current Events: Connecting Past to Present

7. The Power of Information: Igniting Passion Through Research

We can plant the seeds of historical research early on in a course, such as when we ask students to consult biographical sources to understand the motivations of historical figures. Later, after students have integrated the first six goals into their mental framework, we can introduce more expansive projects. Guided, independent research helps students become creators of knowledge, not simply receivers or manipulators of information, and shows them how to explore the world and their potential role in shaping it.

8. Global Citizenship: Learning to Evaluate Ethics and Solve Problems

Moving from the individual’s role in history, we can show our middle schoolers how to use this knowledge to take action. Encouraging students to direct their passions toward civic activism is the essence of character development. It gives young adolescents a chance to make their own history.

History at all levels and in all units poses moral questions to students. Sometimes such inquiries can kick off a chapter in the textbook or the school year, while at other times these dilemmas require students to plunge into additional research. This final goal strives to foster engaged citizens who are ready to lead and equipped to direct their newfound skills toward local, national, and global change.

Planning the sequence: Where to start

Many of these goals are recursive: they come back again and again within a particular unit and throughout the year. I’ve often found it a good rule of thumb to begin with the first three goals, focusing on the individual, before building up to the larger patterns and connections of the last five themes. Introductory hooks at the beginning of a lesson or a unit will grab students’ attention because of the personal relationships established.

However, a unit will work just as well if we start with the big ideas, such as geography or chronology, and then zoom in toward the people affected by these larger trends. Much depends on your students: their background knowledge, their attention span, their interests, and their skills.

In the past decade, I have taught both middle school and high school classes, from geography and current events to world and U.S. history. I’ve used the lessons and strategies mentioned throughout the book at all levels, including the time-crunched space of an AP U.S. history class. Appealing to skills-based and identity-related standards can work for any student in any grade.

These are some interesting points; after all, it can be quite difficult to teach children history if they have very little interest in it. Because of that it helps to follow some of the article’s advice such as finding a personal connection. After all, if you’re students can get more personally involved with the history then it may stick with them more.

The middle school at which I teach wants to further marginalize history by combining history with English. What are the pro/cons of having a humanities when we have testing pressures?

Phil, this is a great question. When English and history are combined, one way to make sure we retain the rigor of history is by picking compelling primary sources. These sources can be analyzed for syntax, tone and diction through an English lens while at the same time providing a way into historical issues.

I am a member of our local historical society and lead a small middle school history club in the school. We are very much a “hands on” group…building log cabins from pretzels, makeing stereoscopes, sunprints and birdhouses and woodburning maps of our community with historic sites, exploring the history of various holiday customs, games, foods through games and activities. While this isn’t all “local” history, we can easily examine how it applied in the past to our community and how it compared to today. This article reaffirms what we are doing IS history. We have the best of both worlds..I get to teach without all the learning goals, they get to learn without expectations other than having fun!

Paula, this sounds like a wonderful club! Thank you for sharing about the fun you and these middle schoolers create together.