How to Scaffold Skills for Student Discussions

See all of Jackie Walsh’s MiddleWeb articles about questioning and discussing here.

How would you rate the quality of student talk in your classroom? Does it help your kids dig down deeper and learn more? Or do you sometimes feel that it’s not the best investment of class time?

Student skills are the means and ends of productive classroom discussions. When students engage in meaningful academic conversation, they are intentional in their use of important social, cognitive, and use-of-knowledge skills.

In turn, when students are deliberate in the use of these skills, they are enhancing their ability to engage in thoughtful discourse in academic settings and beyond—in the workplace and in our democratic society.

We can all agree these are important goals, but we also know that most students do not arrive in our classrooms with a high level of proficiency in these skills. It’s up to us, and we must be explicit in teaching them and in scaffolding their use over time. In this article I want to look at some ways we can do that.

What are the most important skills for good classroom talk?

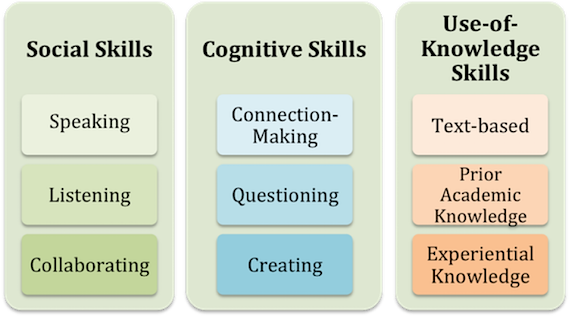

Improving student skills requires focus and intentionality. So where can teachers turn as they think about which skills to spotlight for their students? My colleague Beth Sattes and I have identified a menu of skills, the framework for which looks like this:

(p. 39, Questioning for Classroom Discussion – ASCD, 2015)

The skills probably look very familiar to you as they mirror the requirements of CCSS and other state and content standards. Consider social skills, for example, which essentially determine the quality of student interactions one with another. What connections can you make between the examples listed below and the ELA Speaking and Listening standards embodied in CCSS?

- Speaking Skills

- Speaks at length so that thinking is visible. . . .

- Paraphrases portions of a text. . . .

- Listening Skills

- Waits before adding one’s own ideas. . . .

- Looks at the speaking student & gives nonverbal response. . . .

- Collaborating Skills

- “Piggybacks” and elaborates on classmates’ comments.

- Actively seeks to include classmates who are not participating.

One of the primary instructional purposes of a discussion is to afford students the opportunity to think more deeply about content, to make personal meaning through individual and collaborative inquiry. The use of cognitive skills moves student talk from a simple exchange of information to dialogue involving more complex reasoning or generative thinking.

Use of the kinds of cognitive skills featured below engage students in the levels of thinking associated with levels 2 and 3 of Webb’s Depth of Knowledge:

- Connection-Making Skills

- Identifies similarities and differences. . . .

- Offers reasons and textual evidence. . . .

- Questioning Skills

- Poses questions to clarify and better understand. . . .

- Asks questions to identify a speaker’s assumptions.

- Creating Skills

- Draws inferences from other speakers’ ideas. . . .

- Integrates information from multiple sources. . . .

Attending to discussion timing and preparation

One key to the success of discussions relates to timing—the point in an instructional cycle when they occur.

Not only do we need to position discussions strategically, we should also afford students the opportunity to get ready. Preparing oftentimes engages students in the close reading of a text or the careful review of data generated by an experiment or reflection on a solution path to a problem.

When teachers attend to timing and student preparation as they plan a discussion, they pave the way for students’ thoughtful use of knowledge during the discourse. However, as with social and cognitive skills, students need to know teacher expectations in this area. Three categories of knowledge can contribute meaningfully to a classroom discussion:

Text-based knowledge is central because it focuses on the topic or issue under consideration. This, of course, is not limited to textbooks, but can include supplemental information accessed online or through relevant print sources—both primary and secondary.

Prior academic knowledge can also serve as important fodder for discussion as teachers strive to encourage students to make connections across the curriculum.

Finally, the meaningfulness of a discussion increases as students incorporate relevant experiential knowledge gleaned from out-of-school learning. In our own work, we identify specific skills for each of these three sub-categories, but associate the following with all three.

Using knowledge to deepen discussion

How many of us have had the experience of planning a classroom discussion that ended up feeling like a mere exchange of opinions or, worse yet, a “sharing of ignorance.” Students must understand that the purpose of discussions is to deepen their understanding of content—and that they will be accountable for using knowledge to substantiate their thinking.

- Use-of-Knowledge

- Strives for accuracy in presentation of facts.

- Cites information sources.

- Evaluates the credibility of information sources.

- Relates comments to the subject or question for discussion; does not get off topic.

Scaffolding the development of skills

In our ASCD book Questioning for Classroom Discussion, Beth Sattes and I offer a framework of discussion skills – a total of 47 spanning the three categories – as a resource. We imagine that teachers will scan the list to identify those most appropriate to their students given student age and developmental level and the content or discipline under consideration.

It is not enough to present the skills of discussion to students; teachers need to actively scaffold student development of these skills. Teachers can scaffold directly – through modeling and coaching – or indirectly, by selecting structures and protocols that will shape and guide student interactions.

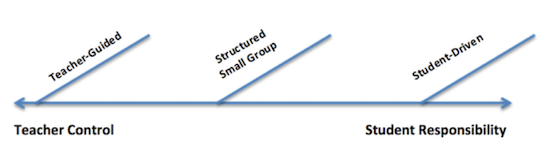

The goal is to nurture and support student learning of the skills to the point that students are able to use them independent of the teacher’s intervention. In our book, we refer to these different settings for discussions as “forms” and present three identified forms on a continuum—moving from more teacher control to more student responsibility.

The teacher-guided discussion comes first

The teacher-guided discussion comes first

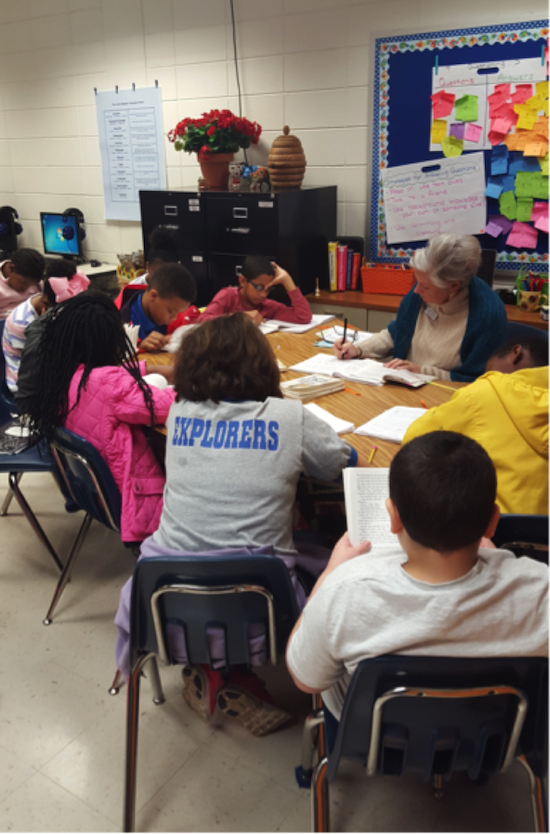

In teacher-guided discussion, teachers assume the role of a “master” discussant who models and coaches student apprentices. As a model, the teacher intentionally spotlights selected skills, thinking aloud to students about what she is doing and why.

For example, pausing when a speaker stops talking is particularly important in a discussion. This “talk-free zone” allows the speaker time to reflect and add to a statement. At an appropriate point following this type of pause, the teacher might say:

“You probably noticed the few seconds of quiet following Jeremy’s comment. This allowed him time to think about what he had said and to decide if he wanted to say more. And he did! During a discussion each of us needs to use this pause to think about what a speaker has said and decide what we think about it. Do we agree? Or disagree? Do we have something to add?”

Teachers can strategically use think-alouds to explain what they are doing as they model key discussion skills.

Teachers also use coaching to actively scaffold student thinking and skill development during a discussion. This often takes the form of offering comments or posing follow-up questions to students. Comments may be simple positive reinforcements of desired behaviors. For example, following a student’s request to hear from a classmate who had not previously spoken, the teacher might comment:

“I really appreciate Alice’s asking for Marie’s perspective. Everyone else had been talking so much that Marie hadn’t had a chance to say what she was thinking.”

During the early stages of students’ learning about skillful discussion, a teacher may need to:

- request that a student offer evidence to support a statement if a classmate does not;

- invite a student who has not been engaged to pose a question or make a comment;

- encourage students to make connections between text-based knowledge and prior learning, and so forth.

During teacher-guided discussion, the teacher is alert to opportunities to provide these kinds of scaffolds in unobtrusive ways that do not interfere with the flow of the discussion. Teacher-guided discussions can occur as a whole class or in small groups, depending upon instructional purposes.

Then we move to structured small groups

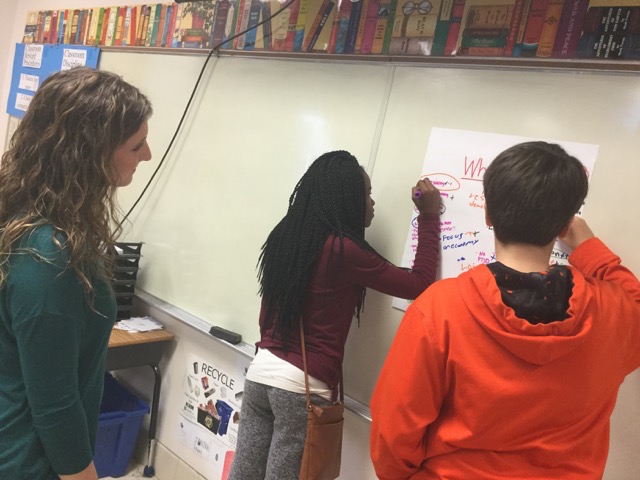

As we move along the continuum, structured small groups are an ideal setting for scaffolding student discussion skills through the intentional use of protocols for this purpose. Protocols provide rules, and sometimes step-by-step procedures, to govern who talks when and for how long.

In our book we provide examples of student discussions using 15 different structured small group formats. Many of these protocols will be familiar to you: Think-Pair-Share, Ink Think, Think-Puzzle-Explore, and so forth. The key to their use in developing student discussion skills and processes is to: (1) be strategic – selecting a structure that is appropriate both for scaffolding desired skills and for deepening student understanding of content; and (2) be explicit with students as to the the specific skills the structures are intended to develop.

Additionally, teachers need to actively monitor students as they interact in small group settings and intervene with personal scaffolding when students are confused or fail to follow the protocol.

Following engagement in a discussion scaffolded by small group structures, students should be afforded the opportunity to reflect on their use of intended skills and the ways in which the structure supported this practice.

And ultimately to student-driven discussion

Student-driven discussion requires the highest level of student skill. Students are required to interact independent of teacher guidance and encouraged to scaffold one another.

Socratic Seminars are a well-known form of student-driven discussion if they occur with the teacher seated outside the circle of discussants. (see here and here). There are numerous similar structures for student-driven discussion. Most place a limited number of students (5-9) in an inside circle and position other students on the outside as observers with specific observation tasks.

Teachers as designers of classroom discussion

Discussion can be a powerful learning strategy for all students—K-12 (and beyond) in all content areas. It does, however, look and sound different at different grade levels and in different content areas. There is no recipe that fits all situations.

Our hope is that what I’ve shared here will lead you to consider using the book in your professional work. We believe it will serve as a useful manual of practice for individuals and teams of teachers who commit to more intentional planning and facilitation of discussions.

A carefully conceived, well-planned discussion has the potential of engaging the minds and hearts of students, increasing their interest in their studies, and promoting a desire for deeper understanding of issues and topics consequential to their learning and being.

Feature image: Jen Roberts, Creative Commons

Dr. Jackie Walsh is the co-author, with Beth D. Sattes, of Questioning for Classroom Discussion: Purposeful Speaking, Engaged Listening, Deep Thinking (ASCD, 2015) and three earlier books on Quality Questioning published by Corwin Press.

She is also a lead consultant to the Alabama Best Practices Center where she designs and facilitates professional learning for ABPC’s statewide educator collaboratives and for the Alabama Instructional Partners Network. She lives in Montgomery, AL. Contact Jackie at walshja@aol.com and follow her on Twitter @Question2Think.

Excellent

Lots of great info here!

Always good to hear about prior knowledge and real life experiences

I appreciated the reminder that students need time to think! Often we don’t allow students the time to “marinate” and come up with their own thinking.