How “Going Deeper” Looks in a Concept Map

A MiddleWeb Blog

Part of the reason is that I’ve focused more on writing and reading and less on graphical representations of information. And the digital world has beckoned enough that old-fashioned paper and markers have sometimes seemed less compelling.

But – as I remembered recently when students spent three days in class and a little more time at home putting together a map on social reform movements – concept maps are one of the most engaging ways to grapple with information and put an individual stamp on it.

So, now that I’m enamored of the idea again, how would I improve the assignment next time?

First and foremost, I would explain more about what it means to show “complex understanding” and “deep connections,” two factors I listed in the 30-point grading rubric’s criteria:

- Deep thematic and chronological connections (10)

- Complex understanding of the nature of reform (10)

- Meaningful facts and quotations that “pop” (2)

- Appropriate parenthetical citations (2)

- Specific or approximate dates for all facts and quotations (2)

- Creative title and your name on the front (1)

- Readable and clear (3)

I graded the eighth graders’ work, I had an idea of what deep connections would look like, but I wasn’t able to articulate graphically how they would appear. Afterward, I realized that the most insightful maps shared a few qualities:

-

Complicated Categories:

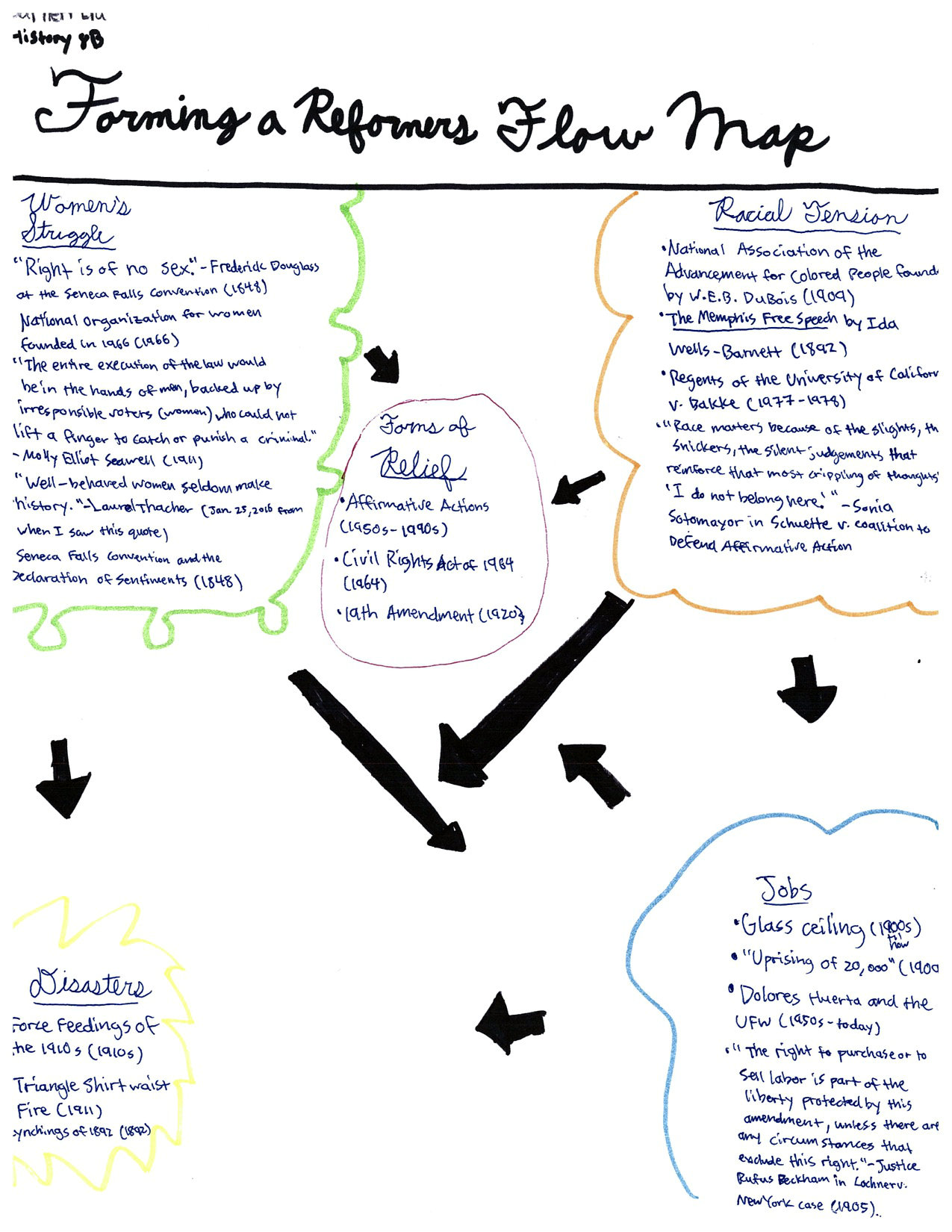

If students used categories, these groupings went beyond “Women’s Rights” or “The Labor Movement.” For instance, Melody titled her concept map “Segregation Within Desegregation,” alluding to the 1978 Bakke Supreme Court decision and also to the ramifications of California’s Proposition 209 from 1996. Taking a different tack, Barnett’s map listed “Forms of Relief” and “Disasters” to show the positive reactions to and negative consequences of various events.

-

Paths Toward Progress:

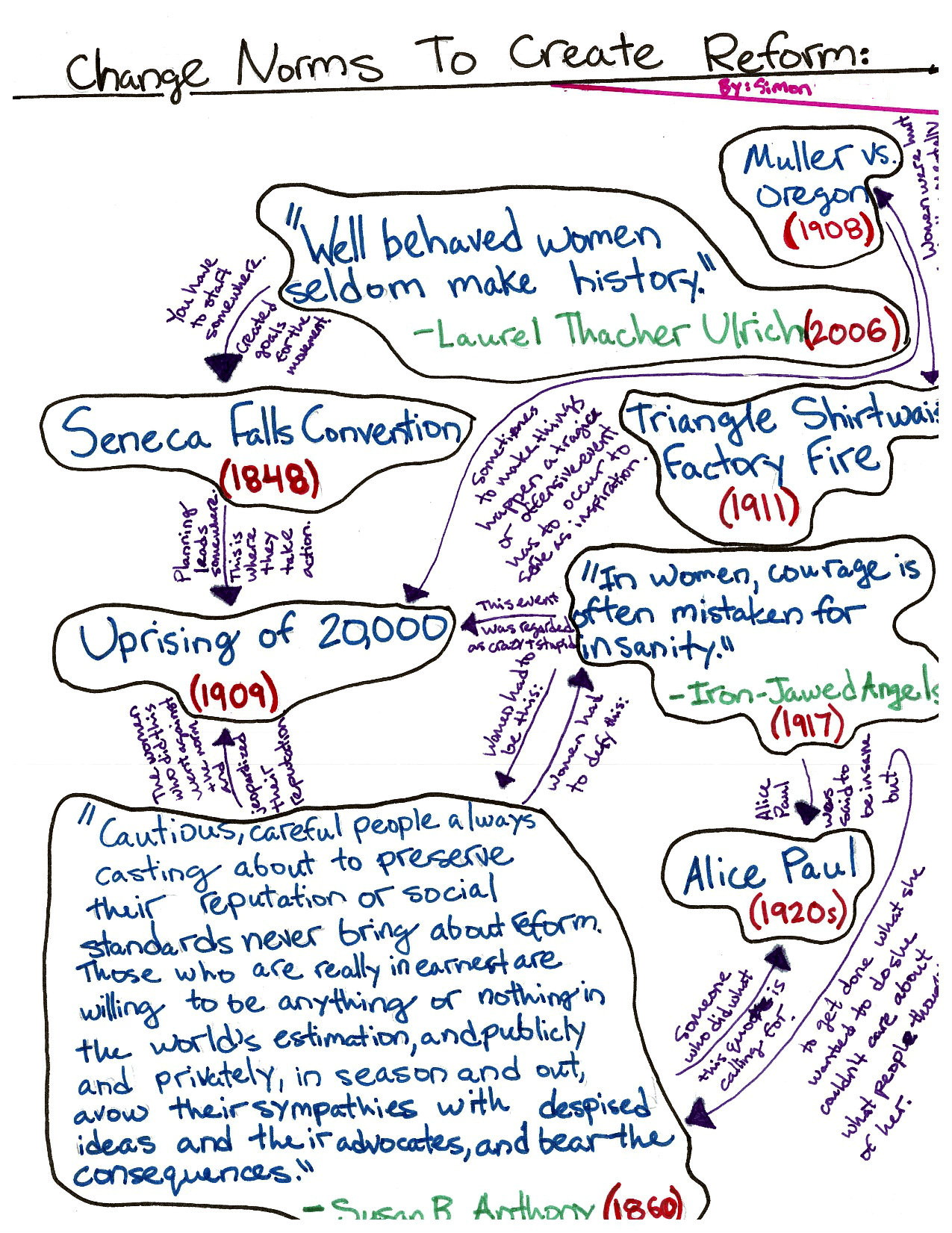

The students who most effectively showed a “complex understanding of the nature of reform” analyzed how reformers accomplished their ideals. To do this, some maps relied heavily on chronological causes and effects, including one by Charlie that cited Sojourner Truth and Ida Wells-Barnett as women who “began stepping into roles usually assumed by men to support their movements.” A map by Sofia indicated two kinds of lasting social change – “The end of racial & sexist discrimination type of reform” and “Equality type reform” – indicating the difference between simply stopping prejudice versus actually working toward equal rights.

-

Annotated Arrows:

Each student wrote 100+ words of explanation on the back of the map, but I found that the best maps almost didn’t need this explanation because they packed so much detail into the diagrams on the front. A number of students wrote comments next to each arrow that explained how events echoed, contradicted and intersected with each other, such as Simon’s observations that “women had to be this/Women had to defy this” and “Planning leads somewhere. This is where they take action.” Such intricate “annotation” of the facts led to more meaningful connections.

Some tweaks for next time

Next time I introduce this assignment, I will show examples like these to emphasize the many ways to go deeper. I will also remember that concept maps, in their representation of students’ understanding, can be not only ends in themselves but excellent prewriting for essays and research papers.

And, best of all, they’re fun for students as well as meaningful for teachers – a chance to break away from the digital world and really dig into timelines and primary sources with paper and markers at the ready.

Thank you for reviving the conversation on the use of concept maps. This may be an oldie, but still a goody! I really enjoyed your reflections on how to assess student learning with concept maps…very helpful. Thanks!

Amy, glad to hear it! The critical thinking involved is so much fun to see.

Michael Milton details a tremendously cool “physical” lesson using kitchen twine and Gorilla tape, in which his students make connections between different concepts/events. It might be an interesting addition to your equally awesome concept map lesson.

http://michaelkmilton.com/2016/01/14/preparing-for-exams-like-a-conspiracy-theorist/

Lisa, this is amazing! Thanks for sending along an expansive 3D version of a concept map.

Hi Sarah – Thanks for sharing your concept map experience. These are fabulous student examples. There are so many programs for creating concept maps, but there’s still nothing like cutting loose with colored markers on a blank page. There’s some decent research showing how they help build deeper understanding.

Your work on clarifying what that means in a rubric is really helpful.

I know this is an older post- but I thought I would share that I love using concept maps as a form of assessment. I turned my second semester exam for 8th grade American history into a three day creation of a Concept map where students show what they know and how history connects. I love it because it is such a deep way to show knowledge beyond a traditional exam. Students have to understand, now just recite to do well.

Erin, this is a wonderful idea for assessment! How did it work – did the students have to know a certain set or number of events and then connect them, or was it open book?