Teaching the Highs and Lows of American History

A MiddleWeb Blog

As I write this, I am still not sure where this is all going. Is this just a quick blip in the news cycle? Or will it gain momentum over time?

This recent controversy is playing out as I am in the middle of teaching my students about U.S. policy towards the Plains Indians in the late 19th century. It is not a story that puts the United States in the best light. The Sioux wars, the flight of the Nez Perce, and the tragedy at Wounded Knee are stories with unhappy endings for the Native Americans.

One of my concerns about starting the school year with this topic is creating a cynicism among my students that our country is “evil.” That is the word at least a handful of my students used after I told them the story of Wounded Knee. I note the connection to a concern expressed by cultural conservatives – that the history taught to young people is not instilling enough patriotism.

We hear this concern from time to time when new education standards are published. We heard it a few years ago when the College Board made changes to the Advanced Placement test in U.S. history. When the cyclical debate heats up, people start counting the number of times George Washington is mentioned in a textbook, compared to Rosa Parks.

Seeking balance on a continuum

But teaching history in a way that instills national pride, awareness, and civic responsibility is not so simple.

You can’t take 2 parts George Washington and mix it with 2 parts Abraham Lincoln, stir in the Civil Rights movement and bake for 241 years and get a perfect loaf of anything.

I do not have the perfect recipe. But I know we are taking a big risk if we whitewash our nation’s past. Middle schoolers are quite capable of understanding that our history has highs and lows, heroes and villains. If we pretend otherwise, we are insulting their intelligence and we risk losing their trust.

Middle schoolers seem to need constant reminders about bringing pencils to class, capitalizing proper nouns, and putting their names on their papers. But not one of them needs help realizing that our country has not always measured up to its ideals.

Skewed stories threaten democracy

Vaclav Havel. Source: David Sedlecký, Wikimedia

Vaclav Havel, the Czech dissident who became the first president of Czechoslovakia after the fall of communism, writes, “Lying can never save us from the lie. Falsifiers of history do not safeguard freedom but imperil it.”

We imperil our democracy if we don’t allow our nation’s football players to exercise their First Amendment rights to call attention to flaws in our national character. We imperil our democracy if we don’t expose our students to our history – good and bad – and the times when we have not lived up to our national creed, that all people are created equal.

Sometimes I think it is precisely because of the high ideals of the Declaration of Independence that Americans have such a hard time admitting the bad stuff. Every nation and every group of people has its dirty laundry. The U.S. is no exception.

But the idea of American “exceptionalism” has perhaps made it harder for us to come to grips with that. The Declaration of Independence promises so much. It is uncomfortable when we see evidence of our leaders and citizens not living up to it.

Pointing out inconsistencies is not unpatriotic

Frederick Douglass made this point in a speech he gave in Syracuse in 1847. He defines – most brilliantly – the meaning of a true patriot:

I make no pretension to patriotism. So long as my voice can be heard on this or the other side of the Atlantic, I will hold up America to the lightning scorn of moral indignation. In doing this, I shall feel myself discharging the duty of a true patriot; for he is a lover of his country who rebukes and does not excuse its sins.

This brings me back to the Sioux Wars, Chief Joseph and Wounded Knee. I cannot excuse our nation’s “sins” as it applies to the harsh treatment of Native Americans. But I’m not comfortable with assigning “evil” either. This is a much more complicated story than that of cowboys and Indians, good guys and bad.

No villains, no saints

W.E.B. Du Bois Public domain

So we had a class discussion about history and judgment. I shared with them one of my favorite quotations from W.E.B. Du Bois, which came from his book, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880.

In describing Reconstruction, he wrote, “There is no villain, no idiot, no saint. There are just men; men who crave ease and power, men who know want and hunger, men who have crawled.”

I use the quotation to make the point that there are few villains or saints in our history. It is a useful theme to revisit as we go through the year. All I have to do is remind them, “no villains, no saints.”

Years ago, while teaching about the Vietnam War, I had a student who raised his hand and asked me flat out, “So Ms. Brown, was President Johnson a good guy or a bad guy?”

We had already studied the Civil Rights movement and Johnson’s role in the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act and his “Great Society.” The student pointed this out, commenting that he thought this made Johnson “a good guy.” But now with the new information about Vietnam, he wasn’t so sure. I don’t recall exactly what I told him. But I know I pointed out that nobody is all good or all bad. Historical figures, like ourselves, are only human and therefore flawed.

Necessary nuance and context

This student’s question sticks with me as a reminder to teach students about the importance of nuance and context. Johnson didn’t intend to make bad choices – who does? – but in part his choices were based on choices made by previous presidents and Congress in the context of the Cold War.

Similarly, decisions about the Sioux and the Nez Perce were made in the context of tremendous pressure from railroad companies, settlers, farmers, cowboys and the industrialization that was transforming the nation. Decisions were made in light of earlier ones made by previous presidents and Congress – the decision to purchase the Louisiana Territory, the decision to remove the Cherokees and other Southeastern tribes to Oklahoma.

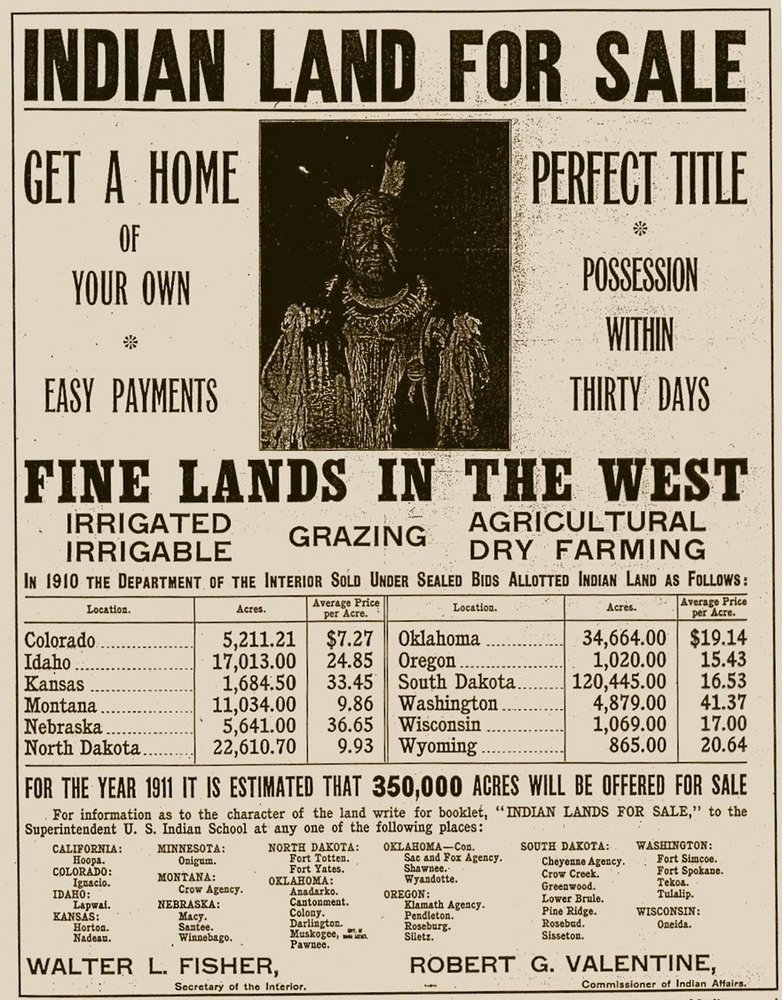

U.S. Department of the Interior advertisement offering ‘Indian Land for Sale’. The man pictured is a Yankton Sioux named Not Afraid Of Pawnee. (Public domain)

In teaching students about the Dawes Act, I have to remind them that it grew out of the concerns raised by reformers like Helen Hunt Jackson who wanted to have a more humane Indian policy. In reference to the policy of assimilation of Native Americans in the Jacksonian era, historian Daniel Feller points out that “One person’s humanitarianism is another’s cultural genocide.”

So is Henry Dawes, sponsor of the Dawes Act, a saint because he meant well? A villain because it didn’t turn out well for so many? Obviously he is neither. History and culture – and human beings – are more complicated than that.

Flag waving is not the answer

I want my students to love their country. I want them to grow up to be active participants in the political process. I want them to do good in the world. To achieve that goal, I will be cautious about making them too cynical. But I will not use patriotism as a way to obscure the truth. Flag waving is not the answer.

Maybe, when teaching, we need to think less about heroes and villains or red, white and blue – less about black and white, and more about grey.

I agree wholeheartedly with your premise. I teach middle school humanities with a history core and just finished a unit on Jefferson, hero or hypocrite? I do this throughout the year for different topics (Gilded Age-robber barons or captains of industry?) Using history habits of mind, where we do not use present mindedness to explain historical events, but have empathy for the times, helps students understand why and how things occurred. Not making it ok, but just a better understanding of the past.

Love it–yes, robber barons or captains of industry is a classic one. I’m starting on Rockefeller and Carnegie this week. Getting students to see that it is not all one or the other, I think, is the key. Clearly Rockefeller, Carnegie and other industrialists contributed much to our economy. And clearly others suffered as a result. And what better example is there than Jefferson himself? Clearly both hypocrite and hero. No villain, no saint. Japanese internment, Cold War issues and the dropping of the Atomic bomb are other great opportunities to talk about presentism and the value of judging what happened in the past based on how things were in the past.