Creating a Safe Space for Difficult Conversations

Among progressive educators, no goal is more holy than creating a “safe space” for learning. Teacher Matthew Kay makes this point early in the first chapter of his important book Not Light, But Fire: How to Lead Meaningful Race Conversations in the Classroom.

Too often, Kay says, teachers simply declare that their classrooms are safe spaces and move on. “We are suddenly ready to lead conversations about sensitive topics, because our students are magically now eager to take risks.”

But for most of our students, Kay writes, “a teacher’s safe space designation doesn’t mean much.” Just saying it doesn’t make it so, for reasons that Kay clearly enumerates in his nuanced and ultimately convincing explanation (pp. 14-16).

Instead, Kay proposes, teachers and students have to create safe spaces together. “In order to nurture hard conversations…first we must commit to building conversational safe spaces, not merely declaring them. The foundation of such spaces is listening.”

Matthew Kay in his classroom at Science Leadership Academy.

Although Kay’s chief purpose in writing Not Light, But Fire is to support other teachers who agree with the need to lead race conversations in classrooms, he wants to be sure that teachers are fully prepared before they begin (as he makes clear in this interview with Larry Ferlazzo). The entire first half of his book is devoted to preparation.

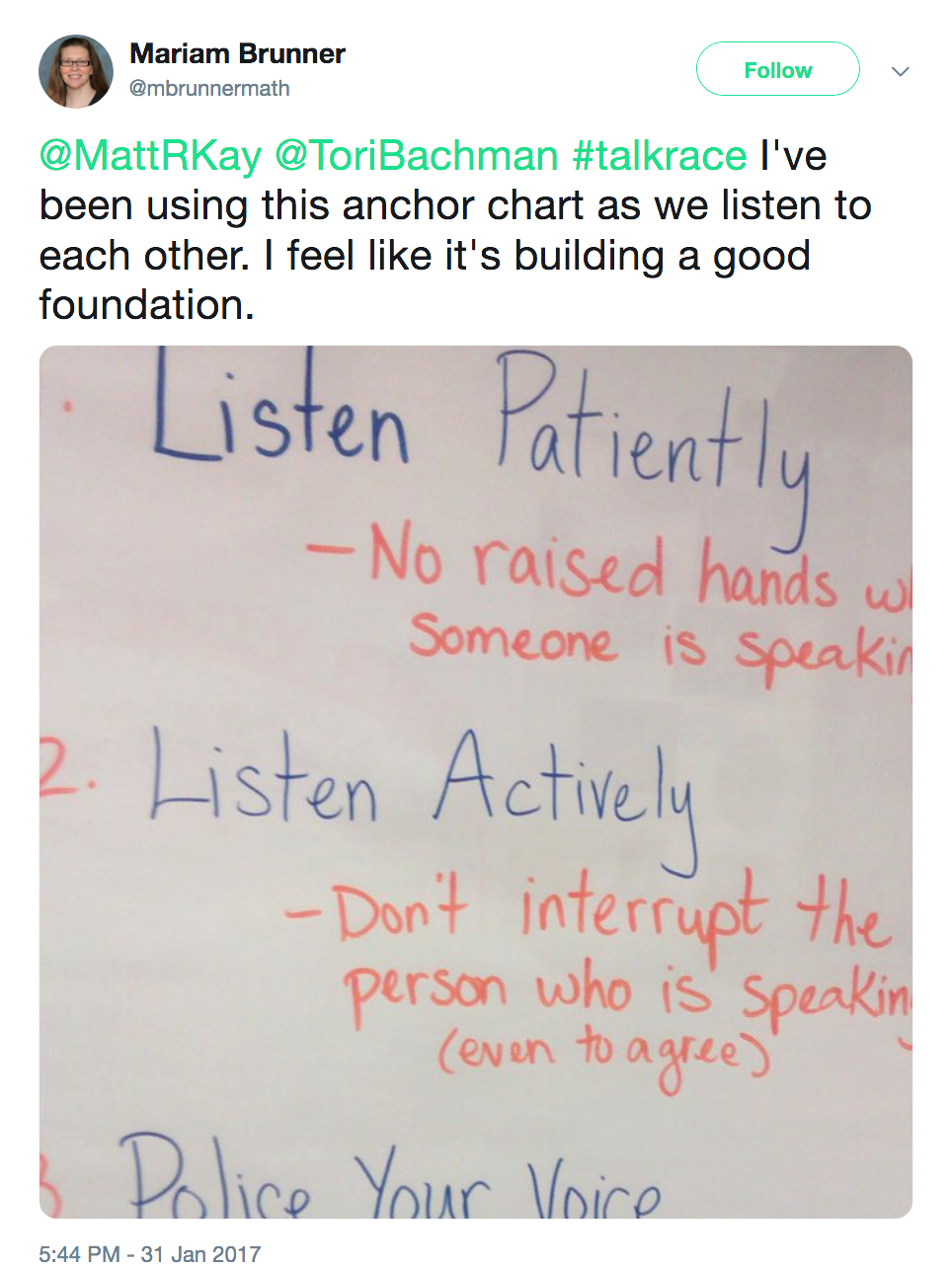

In Chapter 1, one of Kay’s goals is to help teachers think through what it means to “create a culture of listening—an act that can be broken into discrete, practicable, and measurable skills.” He does not offer his method of creation as a “panacea” but shares “only what has worked for me, hoping simply to shift the safe space conversation from the realm of magical thinking to a more practical skills-based approach.”

This is not an easy book to excerpt, in part because it asks the reader to let down barriers and participate at a vulnerable level, and the asking is accomplished gradually over many pages. That said, in summary, Kay is asking that we let him prepare us before we attempt his methods with our students.

What we’ve decided to offer here is a small sample of that preparation. In this excerpt, Matthew Kay shares the three discussion guidelines he uses in his own classroom (at Science Leadership Academy in Philadelphia) to establish the conversational safe space.

– John Norton, MiddleWeb Co-Editor

To Create a Conversational Safe Space, Begin with Listening Skills

In my classroom, the conversational safe space is established with three discussion guidelines: Listen patiently, listen actively, and police your voice. After their introduction, each is practiced explicitly over the first few weeks—a period of time that I like to think of as a conversational “training camp.” This camp works as an extended norming that I reference for the rest of the year.

LISTEN PATIENTLY

The more we care about a topic of conversation, the more we rush to speak. The less we care, the less we feel obligated to pay attention to conversational partners who do. In both instances, we often fail to show others that we are listening patiently to them. This display is important, as people cannot access your brain to measure your level of focus. Social cues are necessary to show people they have our attention.

Practicing this skill requires a shift. Normally, after a teacher calls on a student to speak, we give most of our attention to the respondent. We shift our attention away only when someone else calls out, or behaves in some way that we deem disrespectful. But to help students listen patiently, we must invest considerable focus on the students who are not speaking.

In doing so, I offer some rules: First, hands should not be raised while someone is still talking. When a teacher calls on one student to speak, the rest of the hands in the room have to go down. Any student who does otherwise is communicating to everyone in the room that they don’t care about the person who is still talking. That raised (and sometimes waving) arm is saying, “I wish you would shut up! I have my own thing to say!” This behavior sparks an unnecessary rush for respondents, causing them to speak as if trying to squeeze comments in under the wire, before their teacher dumps them for the other raised hands.

Second, listening patiently means that students should never be interrupted. This is not new. Many teachers have variations of “one voice at a time.” The problem is that too many of us frame the rule as more disciplinary necessity than skill development.

Students who have an impulse to interrupt each other care deeply about what is being discussed—this is a win! Calling out signals impatience, not meanness. Something in the student’s brain is boiling, and the lid couldn’t hold it, but students must be taught that (1) their big eureka might be influenced by what is currently being said, and (2) patient listening is transactional—and when they speak, they will want their classmates to keep the lid on too.

(This is more difficult when students come from environments that define safety as students are quiet . Dialogic classrooms offer so much new stimuli that it’s easy to get wired. Also, students might not trust that they’ll ever get a turn, so they try to squeeze their points in before the teacher shuts down the conversation.)

In my classes, we don’t interrupt for any reason, including affirmations and agreements, both of which still have the unintended effect of drawing focus from the speaker.

Beyond these nonnegotiable rules, there are countless suggestions. Try for eye contact. Try nodding. Try smiling. Try pursing your lips in thought. Students should reflect on what they appreciate from a listener and try to mimic those behaviors when someone else is speaking. Regardless of whether or not they are in doubt, they should ask each other if they feel “listened to.”

Over the first few days of school, and often afterward, I offer various scenarios to illustrate the importance of listening patiently. One student raises his hand, and I ask others to wave theirs while she speaks. How does that make you feel? As a student speaks, I constantly interrupt him with seeming affirmations. “Uh-huh, yeah, uh-huh, yes, I know! Right??” How does that make you feel? A student pauses to gather her thoughts, and I step in with, “That reminds me of . . .” How does that make you feel?

Throughout these scenarios, I pepper personal stories. For instance, as a stutterer, I’ve always hated interruptions, especially the last sort, where people would step in to help me finish, but would instead fling my conversation far from the thread I was trying to follow. “I was going to get there!” I tell students, “if you would have just let me finish.”

A commitment to the language of listening patiently drastically impacts not just students’ peer-to-peer interaction, but our core relationship with students. Consider the following classroom scenarios:

(A) Mike (interrupting Joe, a classmate): Yo! That same thing happened to me yesterday when . . .

Mr. Kay (frustrated): One voice! You’ve got to stop interrupting!

Mike (equally frustrated, whispering to a classmate): Told you Mr . Kay doesn’t like me.

(B) Mike (interrupting Joe, a classmate): Yo! That same thing happened to me yesterday when . . .

Mr. Kay (smiling, holding up a placating hand): Patience, man! Listen to Joe—he’s making a good point! Tell your story in a bit.

Mike: Oh, my bad, Joe .

In the second scenario, Mike’s enthusiasm has survived the exchange. The teacher’s choice to not be adversarial means that we might actually get to hear Mike’s story, as he won’t be too resentful to share it. Also, notice how in the second example, Mike is more likely to acknowledge Joe, whom he may have unintentionally annoyed with his zeal. Both students are likely to leave this exchange feeling listened to.

LISTEN ACTIVELY

Let’s continue from the second classroom example in the previous section. Mike, in this moment, has just been reminded to listen patiently to his classmates. He may be tempted to ask, “Why?” The answer is too often, “To be respectful” or “Because calling out is bad.” The ideal answer should be, “Joe’s ideas are worthwhile to everyone in the classroom community.”

Each idea can inspire another, can inform, can be the reason that no two classroom conversations are exactly the same. As such, ideas should not just be shared, but built on. In order to build, ideas must be actively collected before they dissipate.

Toward this end, we must design structures that require students to engage each other’s ideas and listen actively. In my class, this means notebooks, where students are encouraged to write down classmates’ comments that intrigue them. Student teachers, or occasionally student volunteers, do the same on the whiteboard. Students eventually are encouraged to cite each other in essays as reliable sources, as fellow experts, when such citations are appropriate.

As teachers, we can offer just as much praise to students who thoughtfully build on classmates’ ideas as we offer to those who say cool things. In the early days of a school year, I like to follow the thread of a conversation, maybe even illustrate it on the board:

“Joe said ______, which inspired Mike to tell this story, which Marcia thought related to this character in the play. After she made this connection, Tanya told us about this book she read that seems to back up Joe ’s thesis. I love the way you all are building.”

Consider the following scene, which demonstrates one student’s comment with two teacher responses:

Joe: (recovering from Mike ’s interruption): Um . . . yeah, I was saying that when Troy uses the N-word in Fences, it’s different from when white people use it. Well, it’s the same sometimes when he’s yelling at his son. He wants to make him feel bad. Like white people do when they say it sometimes. But when he’s talking to Bono, because that’s his best friend, the N-word is saying something else. It’s saying, we are real tight, you know?

(Response A) Mr. Kay (turns to next raised hand): Good point .

(Response B) Mr. Kay (pausing reflectively to show patience): That makes sense! So people use the N-word for different reasons—but you are telling me that it can actually make people feel a sense of intimacy with their friends? That’s . . . interesting. (Turning to his classmates.) Joe says that the N-word can make people feel close to each other. Has anyone else seen this?

This redirection, when properly executed, makes listening actively contagious. The trick is to never stop redirecting and to ceaselessly praise students for citing each other. Great discussions become self-rejuvenating creatures, truly student-centered events that rarely repeat themselves — even when the text being discussed is the same year after year. In addition, students don’t feel just safe, but also important. And smart. This makes it more likely that they will speak again.

POLICE YOUR VOICE

The focus shifts here, but still places listening at the forefront. If your classmates have to listen both patiently and actively to you, you must make it easier for them to do so by policing your voice. The teacher is no longer the prime audience, a fact that I make clear to students by pointing to their classmates and saying, “Speak to them.”

Early on in the school year, I constantly nudge my students to turn their faces away from me when answering a question, looking instead at peers. The reminder is gentle, and often excited, as if I am trying to say, What you are saying is too good for just me to hear. Let’s get everyone else in on this stuff!

Source: Jacob Chastain

Classmates are often surprised to have a speaker address comments to the larger group. Many perk up immediately because they are used to one-on-one student/teacher exchanges that they’d felt free to check out of. This encourages the golden moment: when a student, without teacher prompting, asks classmates for their opinions on an issue. Whenever I hear this, I know they are nearly ready to keep each other safe during meaningful race conversations.

The second part of policing your voice is understanding that students (and teachers) should speak succinctly. This means that, as a speaker, you are humbly aware of how much space you are taking up at any given moment. Class time is limited. Students should not speak forever; they should not repeat themselves or deliver sermonettes. Transgressions happen. Our students are young, impulsive, and, we hope, impassioned. But there are ways to redirect that build community and respect instead of just shutting kids down.

Consider the two following scenarios:

(A) Maria: That reminds me of when . . . (A two-minute, quasi-related story follows.)

Mr. Kay (visibly annoyed, cutting the student off at the first opportunity): Yes, but we are talking about . . . and please let other people talk .

Maria (equally annoyed, whispering to a classmate): He’s always cutting me off!

(B) Maria: That reminds me of when . . . (A two-minute, quasi-related story follows .)

Mr. Kay: That’s a great point! I didn’t even see it like that before . . . Quick thing . . . Let’s remember to police our voices, right?

Maria (sheepishly): Oh, my bad, y’all!

As with the previous situations, option B removes multiple layers of unnecessary disciplinary tension. A teacher now has the language to say, I appreciate that you care enough to speak passionately in my class. Thank you for being awake! However, I need you to realize that other people are also awake, and they deserve the opportunity to speak as well .

This particular interaction, however, requires an extra step. It helps to pull Maria aside after class to introduce her to (or remind her of ) strategies for being succinct. She could consider pausing before she speaks to gather her thoughts so that she gets right to the important parts. She could work with me to build a reliable structure for her comments, like the one that career coach Lea McLeod published in her article “3 Smart Ways to Keep Yourself from Rambling” called P-R-E-S. (First, state your Point—the main idea, then your Reason—why you think so, then an Example—the evidence that backs you up, then offer Summary—restate your main idea.)

There are many strategies out there. After this initial conversation, it’s important to follow up with Maria, praising small successes with whatever strategy she ’s decided to try.

A final, important note: We should acknowledge that a student who seems to ramble or have trouble following a conversational thread may have social anxiety or another learning difficulty. If you notice this happening frequently, be sure to bring in the rest of the student’s support team, just to double-check that the student is getting the needed supports.

PRACTICE LISTENING

Patient listening, active listening, and policing your voice establish a good conversational foundation for the heavy stuff. But introducing the skills isn’t enough; they must be framed and practiced. For me, there is the aforementioned “training camp” period. During the first few weeks of class, my students hold many practice conversations, in both large- and small-group settings, after which we reflect, not on the topic but on how well we listened to each other. Over the year, we openly try to climb from level to level in each skill. For example:

Listen Patiently

Beginner: Students no longer interrupt each other / raise their hands / talk while others are talking.

Advanced: Students exhibit good nonverbal “I am listening thoughtfully to you” behaviors.

Listen Actively

Beginner: Students reference each other’s comments in their own.

Advanced: Students follow up that reference with a high-order question to their classmates that pushes the conversation forward.

Police Your Voice

Beginner: Students don’t ramble on or stray far off topic when called on.

Advanced: Students apply public speaking techniques of projection, articulation, etc., when speaking in class. They follow up by asking classmates if they were clear.

Teachers Need Practice Too

And just as our students need to practice, so do we. Over our careers, many of us have developed instinctive overreactions to students’ listening mistakes. Not to mention how often we find ourselves lacking the same listening skills we’re trying to teach.

How patient are we? My biggest problem is an instinct to interrupt students. It comes from a good place—I am eager to encourage. But that doesn’t matter. I also have trouble policing my voice, especially when the subject is something I know more about than my students.

The best and worst thing about practicing these skills with students is that they have the language to call me on my own mistakes. Yet, their doing so is evidence that I’m that much closer to my ultimate goal—safety. My students know that their ideas are the sacred currency of our classroom, and that they will be received with a purposeful and structured empathy. Only from here can we can move to meaningful conversations about race.

He is the author of Not Light, But Fire: How to Lead Meaningful Race Conversations in the Classroom (Stenhouse, 2018), from which this article is adapted. Read four reviews of Not Light, But Fire here at MiddleWeb.