How and Why to Assess in Multiple Languages

A MiddleWeb Blog

When Dr. Margo Gottlieb, one of the co-founders of WIDA, shared that she was coming out with a book called Classroom Assessments in Multiple Languages, I was excited and scared at the same time.

When Dr. Margo Gottlieb, one of the co-founders of WIDA, shared that she was coming out with a book called Classroom Assessments in Multiple Languages, I was excited and scared at the same time.

I was excited because I have seen firsthand how students become more engaged and successful at schools when they are allowed to use their home language.

I was scared because I didn’t know how to assess students in their home languages when I did not know the language.

Home-language usage

Before we talk about how we can incorporate home languages when assessing students, it’s important to pause to consider the power of home language use.

Research suggests that the more established a student’s literacy skills are in their home language, the more they are able to acquire a new language (Cummins, 2014).

Students who can read in their home language have established skills such as phonemic awareness, decoding, fluency, vocabulary, and reading comprehension strategies. Students who can write in their home language have developed sentence structure concepts, transitions, punctuation, and the ability to describe, narrate and explain, just to name a few.

Students who have these literacy skills can easily transfer many of them when developing literacy skills in a new language. Home languages are assets that teachers can build on and draw from as students learn in a new language.

Embedding home languages into assessments

Does this mean we have to have essays, reports, and displays in multiple languages when we only speak one?

No!

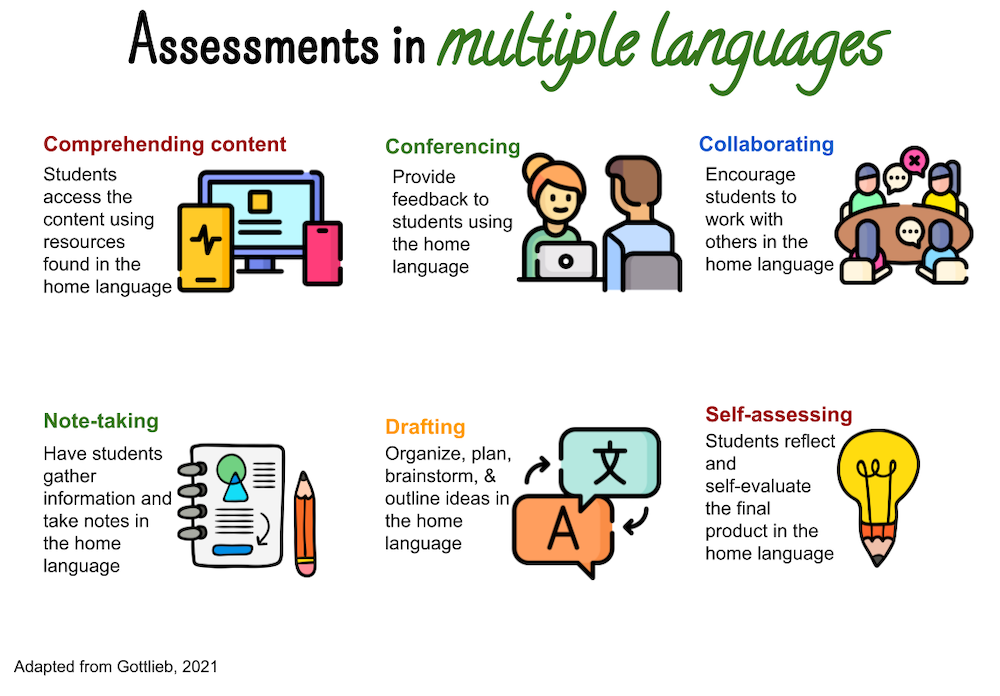

Creating assessments in multiple languages means encouraging students to use their home language throughout the assessment process. Below are different ways to embed home languages into evaluations.

Comprehending content

In assessments students are required to show understanding of the content. Students can access the content that will be assessed in their home language. I once had a Chinese student, Zheng Hong, enroll at my school. One of his assessments in science class required him to explain how individual animals impact the ecosystem.

I knew that the science teacher was going to show the class this video about how wolves changed rivers in Yellowstone. During co-planning, the teacher agreed to turn on the closed captions in Chinese for Zheng Hong to understand the video. We did not make the task easier. We just made it more possible for Zheng to understand the content.

Conferencing

If you have fluency in your student’s home language, then by all means hold the conference in the shared language. You can also leave written comments in home languages if you are comfortable with that.

If you and your students do not speak the same language, conduct conferences in their home language using technology. I have had many conferences with beginning language learners with the support of Google Translate. In the photo below, I am working with Ayaka, a beginner from Japan. I went to her art class to help her understand the instructions. During our conference I had her open Google Translate, and I typed in a question. She then used Japanese to communicate her understanding. Google Translate is far from a perfect solution, but it does help assess students’ understanding at a formative level.

Note-taking

My students do a lot of research for my social studies classes. They often choose to write in English because that is their most proficient academic language. However, for beginners like Zheng Hong, they can write their notes in their home language. Students’ understanding of the content is more important than the particular language they use to take notes.

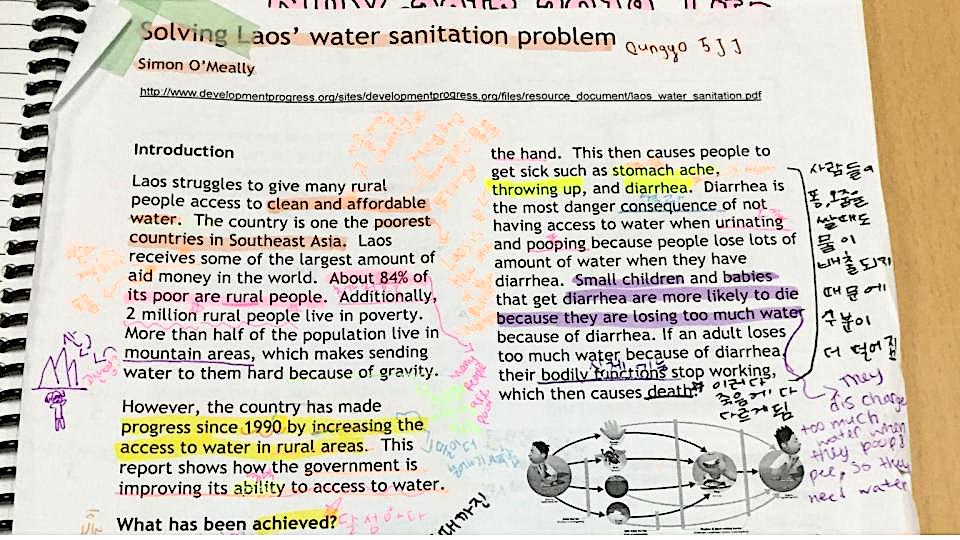

Annotating a text is a form of note taking. I often encourage my students to annotate in their home language as Ungyo did with this article about addressing the water sanitation issue in rural Laos. The article was in English, but Ungyo used Korean to process the content. The content did not change nor did the assessment lose its rigor when Ungyo annotated in Korean. The content of the article is now more comprehensible, which leads to greater achievement on the assessment.

Collaborating

Students can use their home languages as they collaborate with other classmates to create a final product. The submitted work might be in English, but the process of producing the final work can be done in a mix of languages. It’s translanguaging at its best.

We can structure any activity into a collaborative one such as reading an article, watching a video, writing a paragraph, and conducting an experiment. Have students work together using their home language to raise students’ comprehension of the content and engagement with the lesson.

Self-assessing

Students can self-evaluate their work and reflect in their home languages too. Students can speak or write in their home languages to evaluate how successful they were on the criteria for the assessment. They can also reflect on what skills they developed, the process, and the understandings they gained from the long-term project. Students can then share these reflections with their families.

Drafting

Students can also brainstorm ideas in their home languages via mind maps, organizers, sketchnotes, or outlines. For students who are more competent in their home languages, drafting the ideas in non-English will be a more fluent experience for them and more supportive in forming connections between ideas.

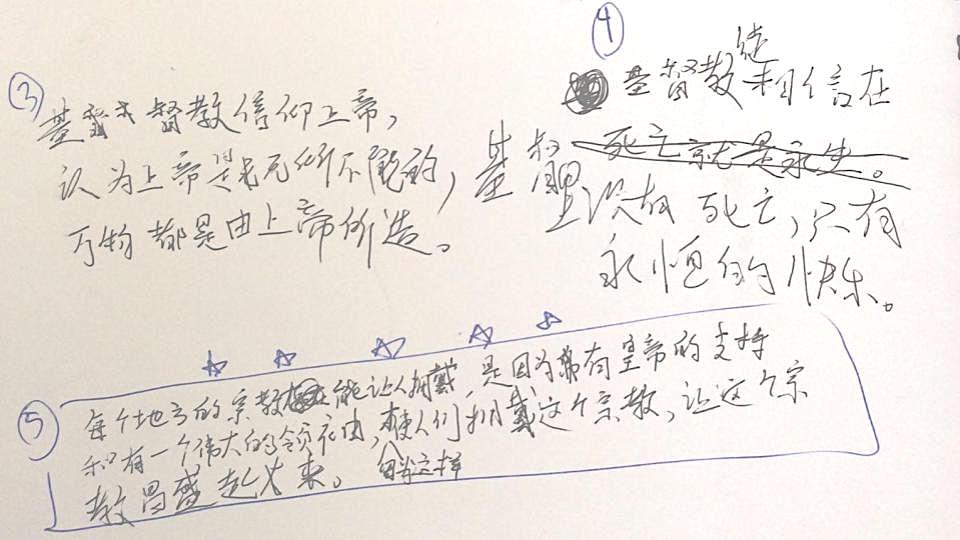

Below is an example of Jasmine’s brainstorm. She listed in Chinese 5 ideas that she could write about for the report. When I came to conference with her, I asked her to identify the ideas she was most interested in researching, and she chose the fifth option. Brainstorming in Chinese was a springboard to writing the report in English.

Actual multilingual assessments

If your home language knowledge is proficient enough, then go ahead and assess in the student’s home language. As long as you can provide evidence for students’ mastery of skills and understanding of content, then take advantage of the fact that you share a common language with a student. In this way students will shine the most because they can engage with their home language and display their strengths.

Make sure to talk to your administrator and consult the school language policy, though, to see if assessing in a shared home language is a recognized practice at your school. If not, then this would be a wonderful opportunity to start a conversation about updating the school language policy.

Conclusion

On a final note: We can adopt a whole-school approach to using home languages by conducting admissions interviews in a home language – if we have the language resources available among our faculty. Students’ guardians will most likely accompany the student, so use this time to learn about the new student and their family. Hosting the interview in their home language also shows that you are welcoming the family into a school that values their culture and language.

Even if you don’t know their language, you can use tools like TalkingPoints to bridge the language divide. When schools reach out in students’ native language, families feel that they can interact with the school now that language is not a barrier to communication.

We cannot change the fact that interim and annual assessments are done exclusively in English in most places in the U.S. and Canada. We can reimagine how we are assessing students during our day to day teaching.

We do not have to have final products produced in multiple languages. We can still encourage and facilitate engagement with the assessment by using their home languages anywhere we can.

You can hear Tan’s Teaching MLs podcast featuring Margo Gottlieb here.

References

Cummins, J. (2014, November 14). Reversing Underachievement among Immigration-Background Students: What does the research say? Politeknik.