What We Want Students to Know About the Media

A MiddleWeb Blog

When I posed that question during our live virtual gathering, I received a number of good responses from participants, including:

-

- check the source

- analyze for accuracy and bias

- know how to “fact check” what you see

- use multiple sources

- don’t believe everything you see or read

- how to find out what is real and what is fake

- don’t trust all you read

While those answers were good, they were also expected. They emanate, for the most part, from librarians whose professional training, experience and primary focus has been “information literacy,” not “media literacy.” (There’s a big difference, and during my talk I made sure to elaborate on what I believe sets them apart. More about that shortly.)

My Four Answers

I offered four suggested answers to my own question:

First, I want students to know that media is pervasive. It’s powerful and almost inescapable. [Can your students name a place they occupy where no media exists?]

Second, I want students to know that the media are persuasive and influential. Media sets agendas by what it reports (and what it does not) and in many ways tells us what to think, feel, eat, drink. (Can your students offer one or more examples of persuasion and influence in the media they engage with?)

Third, I would want students to know that most media exist to make money, and the decisions media managers and editors make are often based on profit potential. (I like to ask students: who benefits from your purchase of a magazine? Who profits when you click on a link and land on a page filled with ads?)

Fourth, here is something I want young people to know that moves the power of media beyond money-driven objectives. Our students can use the media to produce and distribute messages that address problems and challenges in our community and our world. [See, as an excellent example, “Student Filmmakers Document Social Justice Issues in Their Own Voices”.]

So after asking librarians “what do we want students to know about the media,” I challenged them (and now I challenge you) to consider this second question: How will you insure your students are fully aware of “the media” and all of its ramifications?

Information Literacy / Media Literacy Explained

Now consider this definition of media literacy: “It provides a framework to access, analyze, evaluate, create and participate with messages in a variety of forms — from print to video to the Internet. Media literacy builds an understanding of the role of media in society as well as essential skills of inquiry and self-expression necessary for citizens of a democracy.” (Source)

My experience as a media literacy consultant leads me to believe that many school-based educators would benefit from more media literacy professional development. The need for media literacy lessons in our classrooms has never been a higher priority. Every educator needs to understand what it is, how important it is, and how to weave it into daily instruction.

How To Address Media Literacy in Instruction

If you use video or images in instruction, you have a perfect opportunity to inject a dose of media literacy (which includes visual literacy) into your lesson planning.

Helping develop students’ critical viewing skills (CVS) is essential in a 21st century education. Most of our students view media passively — they watch with the thinking parts of their brains (mostly) turned off. Media and visual literacy encourage us to view media actively. That means being engaged (turning “on” those thinking parts) as we experience what we see.

Consider this definition of active viewing:

“You are paying your full attention to one task (such as watching television) and you are also interacting – you question what happens on screen and want answers.” (Source)

Engaging Students Across the Curriculum

Engaging students in critical thinking about media is not super challenging. But it does take some practice. Here are some examples:

► An arts educator, displaying a famous painting to students, guides them to look beyond the superficial.

► A history teacher, projecting a photo from the Holocaust, encourages students to use inference as they look for clues in the image.

► An elementary educator explores the use and meaning of color in signs.

► A science teacher has students explore what special effects techniques a filmmaker used to make a scene appear authentic.

► A math teacher challenges students to consider “who benefits” and how they benefit when advertisers spend $6 million for an ad during the annual Super Bowl game.

If you’re reading this MiddleWeb media literacy blog for the first time, you might like to know that in the past four years, I have explored media literacy’s connections to pop culture and current events and what that means to teaching. (Go here to explore my previous posts.)

Simply using media in instruction today is not enough: we must take time to help students better understand media messages. That’s where “media literacy” education comes in. It encourages us to take students through a “deep dive” into media’s purposes and meanings.

Every teacher I know uses “the media” in instruction, but not every teacher teaches ABOUT the media. There are opportunities to remedy this situation. And those opportunities exist, in part, in our teaching standards.

Media and Media Literacy in the Standards

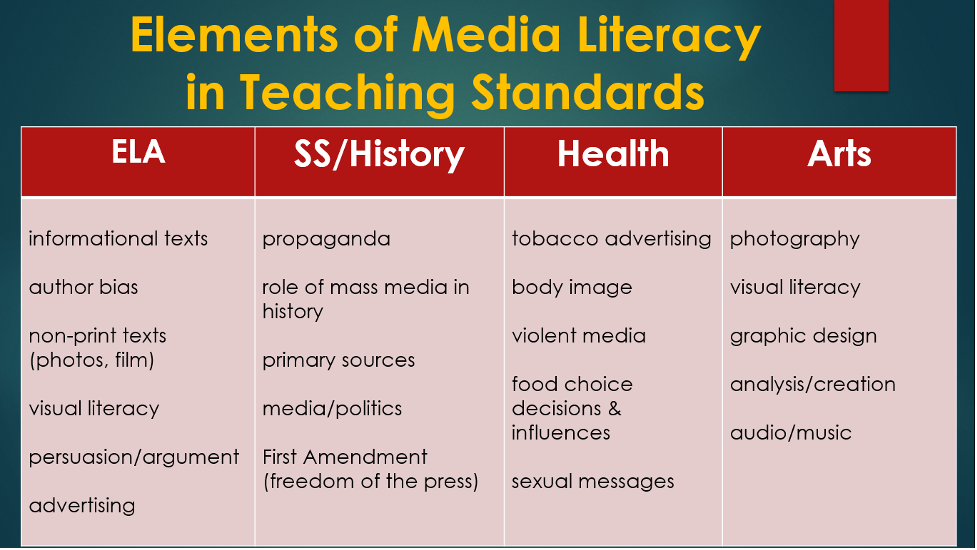

In a 1999 op-ed in Education Week Professor Robert Kubey and I elaborated on my analysis of every state’s teaching standards. At that time, elements of media literacy were found to exist in most state’s standards for ELA, Social Studies and Health. Here’s the data we shared:

A decade later, the introduction of Common Core standards wiped out many of those media literacy elements in state standards. As another colleague and I wrote in a 2011 Ed Week commentary:

“(O)ther than a mention of the need to ‘evaluate information from multiple oral, visual, or multimodal sources,’ there is no specific reference in the common standards to critical analysis and production of film, television, advertising, radio, news, music, popular culture, video games, media remixes, and so on. Nor is there explicit attention on fostering critical analysis of media messages and representations.” (source)

If media literacy is to gain traction, new and revised standards must contain specific language that includes contemporary media and contemporary media literacy.

Gains in Media Literacy Education

Despite those Common Core shortcomings, many groups now recognize and recommend engaging students in critical thinking about media.

• The Definition of Literacy in A Digital Age (Source)

• The Report of the NCTE Task Force on Critical Media Literacy (2021) offers a detailed action plan. (Source)

✻ The National Council for The Social Studies (NCSS) provided members with a position statement on media literacy. In additionm the newly developed C3 (College, Career, and Civic Life) Framework contains strong media literacy elements—such as “inquiry is at the heart of social studies.”

✻ The National Science Teachers Association (NTSA) “strongly supports students’ scientific literacy by including personal and societal issues.” (Source)

Among other education-related groups recognizing the value of media literacy are the Partnership for 21st Century Skills; the Horizon K12 Report; IFTF’s Future Work Skills 2020; and the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards.

Final Thoughts

Do you feel as if teaching “media literacy” should be a priority? I do. That’s because recent surveys and studies have made it clear: many of our students don’t think critically about the media they come in contact with, including social media. [See this WSJ article: Most Students Don’t Know When News if Fake.]

Many of the young people we often describe as “digitally savvy” don’t consider the source of something they read or watched on Instagram, TikTok, YouTube or elsewhere. Others don’t consider the ramifications of spreading fake news or conspiracy theories.

There is no time like the present. What will you do? I invite your ideas and reactions to this post – in the comments below or by email: fbaker1346@gmail.com

Frank W Baker maintains the nationally recognized Media Literacy Clearinghouse website for educators. In 2019 he was recognized with UNESCO’s Global Alliance Partnership in Media & Information Literacy award. He is a member of the 2021 NCTE Task Force on Critical Media Literacy. Baker is also the author of Close Reading the Media – a book of monthly ideas and lessons – published by Routledge in partnership with MiddleWeb.

The more I think about this important subject, the more I think I need to add a fifth to the “What Do Students Need To Know About The Media.” Students also need to know how easily media can be manipulated and shared. And perhaps many of them are already experiencing this via digitally altered images, memes and deep fakes. We need to think seriously how about we address this too in instruction.