Creating Practical PBL Units for History Class

A MiddleWeb Blog

By Shara Peters, Jody Passanisi, and Doug Hinko

By Shara Peters, Jody Passanisi, and Doug Hinko

Have you tried Project-based Learning in your history or social studies classroom? Was it awesome? Was it challenging?

And, if you haven’t tried to implement PBL, what’s stopping you? Predetermined curricular standards? Pushback from admin? A difficult fit with the school culture?

We’d like to argue that you can and should implement Project-based Learning in your history classroom. It doesn’t have to be perfect. Take some elements of PBL and try them a bit at a time. Small steps can turn a stale unit into a truly meaningful, real-world learning experience – even if it’s not pure PBL.

The essence of PBL

Project-based learning has many proponents, and truly there isn’t one way to do it “right.” However, it’s highly likely that most advocates of PBL will agree with the idea that the project should be student directed. The teacher should be there to support the students, but ultimately, the students create and demonstrate learning in their own way.

Project-based learning has many proponents, and truly there isn’t one way to do it “right.” However, it’s highly likely that most advocates of PBL will agree with the idea that the project should be student directed. The teacher should be there to support the students, but ultimately, the students create and demonstrate learning in their own way.

There are other important aspects to PBL that can and, many would argue should, be utilized – like the notion that there should be an authentic discovery taking place, and that the product that comes as a result of that discovery should have an authentic audience.

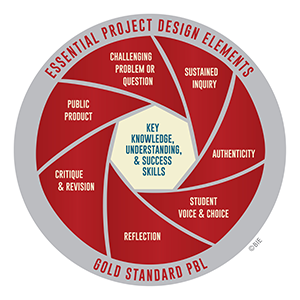

These “gold standard” concepts (see Buck Institute infographic) can discourage some teachers from even attempting a PBL unit or project. While it would be amazing if each student had the ability to make the connections and find relevance on their own, it has often been our experience that students of middle school age need scaffolding and teacher support to be able to do this.

In other words, the pure PBL model sometimes doesn’t fit with what we hope the students will uncover, or they may not yet possess the skills/tools necessary to independently produce the kind of highest-quality, purposeful projects we would wish for.

Good PBL takes some time

Jody and Shara’s students tackled the Civil War in an earlier project.

Additionally, good PBL takes time. Students need opportunities to return to their original idea or plan and make adjustments as they learn more information, make mistakes along the way, and take into account the opinions of others.

While we wish we could always let students discover information at a leisurely pace, we have curricular expectations to meet. It can be argued, of course, that the skills learned through PBL could be as important as any curricular expectations. But for many of us, practical realities come into play.

One of the most appealing aspects of authentic Project-based Learning is that it requires students to synthesize many skills: to do research both on and off line, to navigate tech tools and applications, to collaborate and solve problems, etc.

Middle school students, depending on their experiences in school and level of access to resources, often need extra support and reflection in building these skills, which we must account for in our lesson planning.

Our Medieval China project

So, we knew a few things:

- We wanted our 7th grade Medieval World History students to engage with PBL during their China unit.

- We couldn’t add any more teaching time to this unit than the 10 hour-long periods already allotted in our calendar. Subtract one period for the summative assessment and one period for synthesis/review and we had eight hours to work with.

- Our students did not have very much experience in previous years with true PBL and would need a lot of help building their toolkits.

Direct instruction

To help establish historical context, we taught a series of mini lessons about Medieval China that took up half a class period. At the end of the unit, we quizzed the students on the unit’s learning objectives. As a side note, our students performed better on this assessment than they did on any other unit assessment so far this year.

The project prep

One of the biggest challenges of implementing PBL in a history classroom is finding avenues through which students can engage in inquiry-based learning about things that happened a very long time ago yet present their findings in relevant, contemporary ways that relate to their 21st century world. It’s hard to guide students toward making a real-world connection that does not seem contrived.

Given our content, the PBL entry point that we found was to have students focus on one of our recurrent course themes:

Innovations are created to serve the people’s needs of a particular historical context, and often have long-lasting implications.

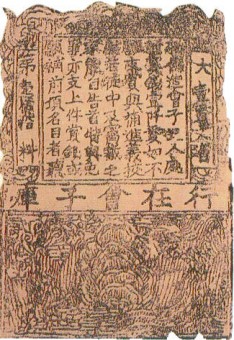

This allowed students to build a bridge from the historic time period we needed them to learn about to the current times that we wanted them to learn about. They chose from a list of innovations that are credited to Medieval China and then created a 90-second Public Service Announcement that made the case that [whatever innovation they chose] changed the world.

Given that this project was completed largely outside of classroom time, we had to carefully plan each step of the process as well as set clear student expectations. We created a series of handouts that walked students through the steps necessary to identify their topics, learn relevant content, organize that information, plan a video, and then create that video.

After our daily half-lesson of direct instruction, student teams met to work on that day’s project segment and to decide what work should be divvied up and completed on their own before our next class. After six meeting days, and two entire classes dedicated to filming and editing, the videos were complete.

What worked for us

Some teams took their projects to the high level we had hoped for. For example, one group that studied the compass made a PSA informing viewers that while the obvious was true – the compass aided navigation and made distant travel possible – an unintended offshoot was the intercontinental spread of disease.

This conclusion was not teacher-directed; it was the kind of high level thinking and learning that teachers hope will happen when they let go of the reins and tell the students, “Go!” And they did! Thanks to iMovie and an impromptu green screen (green butcher paper taped together), this team delivered their report from the deck of a Chinese merchant ship about to be attacked by pirates.

A few teams had to scramble at the last minute to complete their work, and that can be expected at this age – but for the most part, students were able to complete their videos in the time allotted.

Our faculty collaborated too

Another success of this experiment was that as a faculty, we were able to join together and exemplify the type of collaboration in which we would hope to see the students engage. Our team members included:

- Classroom Teachers – partner teachers organized all of the moving pieces of this project, helped students navigate collaboration hurdles, and aligned the project with our course content.

- Director of Educational Technology – helped plan the scaffolding to guide the students through the project, helped students use different filming and editing techniques to create their PSAs.

- Librarian – ordered relevant books for a classroom library that students could use for research, instructed students how to use electronic data organizing systems to document their research findings.

- Innovation Lab Director – guided students toward available relevant resources when creating their videos.

Lessons learned and future iterations

While this project saw many successes, we quickly identified ways in which we can make the experience more memorable and engaging for students.

First off, we provided students with a “menu” of options for types of videos to produce. Some of these video formats were more simple (slide shows and music, etc.) while others required a more artistic and creative twist. Most of the groups did not step outside of their comfort zone to try something more artistic such as a claymation or stop-motion.

Next time, we will definitely brainstorm ways in which to better leverage creativity and arts without sacrificing the integrity of the history content. This would include devoting time to teaching specific technology and production skills that we want our students to synthesize in their projects.

We were also dissatisfied with the level to which our students really understood the concept of inventions impacting the world. Most groups said something like [their invention] influenced the world today because versions of it are still used today. In the future, we hope to do a better job of guiding them toward seeing how parts of the world are different than they might have been because of their invention.

PBL as a work in progress

This project was an experiment on many levels, but our primary question was how to balance teaching students course content, research skills, and technology skills while still stepping back and allowing for student-directed learning. We learned a lot about doing this, and we’ll do better next time.

How have you navigated these dilemmas in your teaching practice?

Read about Jody and Shara’s Civil War PBL project here.

Jody’s book History Class Revisited features

tools and projects to engage

middle school students in Social Studies.

Joining Jody Passanisi and Shara Peters for this Future of History post is Doug Hinko, Educational Technology Director at a preK-8 independent school in Los Angeles. Doug has a B.S. in Elementary Education from Northern Illinois University and an MA in Curriculum Development & Instructional strategies from Concordia University. Find him @dddouglass.

Compass Credit: Science Museum, London, Wellcome Images

Thank you for your relevant blog on PBL in middle school history class. As a PBL trainer and coach, I’m excited to be able to share this with our middle school teachers. Keep blogging and sharing!

dear I’m also a history teacher and in much need of new ways of project based learning ;need help in this regard.

This is great, and the best thing about it is the honest reflections. Are you sharing any of your resources for this PBL anywhere? Thanks for writing this – it has sparked off some exciting ideas!

Thank you so much for sharing your journey… It has been very helpful for me.

Thank you for sharing! Do you have any resources or lesson plans you’re willing to share?

Check out Jody and Shara’s Civil War PBL unit in this post, which includes more reflection about the elements of an effective project.