Writing Digital Argument: A New Student Skill Set

A MiddleWeb Blog

Digital texts abound in the lives of our students. They navigate through the terrain of multiple social networking sites, watch and create videos for YouTube, add and comment on images to Instagram, and gather information from the visual world of infographics.

Digital texts abound in the lives of our students. They navigate through the terrain of multiple social networking sites, watch and create videos for YouTube, add and comment on images to Instagram, and gather information from the visual world of infographics.

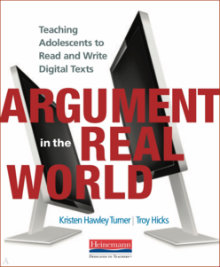

Writers Troy Hicks and Kristen Hawley Turner believe that at every step of the way, we all are not just encountering digital writing in ever-growing abundance, but that every text we encounter along the way offers the potential for engagement of argument.

I recently sent Hicks and Turner some questions that I had about their topic, and they were gracious enough to respond together as a team to my queries.

Troy, you have done and shared a lot of work and thinking about the nature of Digital Writing. Kristen, you have done your share of work with Argument Writing. Of course, both of you have written on many topics. But I am curious, what brought the two of you together for this particular book, which combines those two ideas of digital writing and argument writing together?

We have collaborated on several projects over the years that focus on issues of digital literacy. While we were working on Connected Reading, we really began to explore the impact technology has had on reading, writing, and thinking, and we also began to view digital texts from a lens of argument. By looking closely at what students did when reading digital texts, we also had many conversations about how as digital writers we were making moves of argumentation that were different from just words on a page.

Using image as evidence and inserting hyperlinks in composing multimodal texts such as infographics made us think about how writers are extending arguments with digital tools. We wanted to know more, and this book is the result of our deconstructing the digital texts we – and our own children – encountered and created in our daily lives.

This will be no surprise to the two of you, but I am interested in ways that Digital Writing can be different from, and build off of, traditional writing. You explore this notion quite a bit in your book, particularly in the first few chapters. What are some ways that media can be used to make a rhetorical argument that you might not be able to do in the more traditional, non-digital writing? Is one approach (say, digital argument) more effective than the other?

We spent a lot of time thinking about the term “digital argument,” and ultimately, we learned in our research that the term really needs to be pluralized. There are many modes (or genres) that can present arguments in digital form. Ultimately, the choice of mode for the writer is going to depend on audience and purpose, much like in a traditional context.

For instance, one could make an argument about an important issue such as climate change or mass incarceration by generating an infographic, recording a podcast, or creating a digital video. Being able to embed arguments in a larger conversation (the network) that can be accessed with the click of a link is the primary affordance of digital texts.

Ultimately, a writer needs to consider the academic, social, or political conversation she is entering, how she can best enter the conversation, and what claim she wants to make. The mode/genre/form of the argument evolves from identifying those purposes and audiences, and the writer will choose appropriate media in order to create an appropriate, logical argument.

We’re in strange times when it comes to views about information and news outlets. With calls of “fake news” coming from all sides and clear trends of people reading news only in their tailored social media streams (at least according to Pew Research) it seems as if it is more important than ever to help our students navigate, and curate, the information coming at them on all sides. How does the concept of “argument” play into this media landscape?

Building off the work of Angela Lunsford and John Ruszkiewicz, we make the case in the book that every text we encounter in our digital world is an argument. When a writer posts on social media, the post, in and of itself, makes a claim. Despite the fact that many people say “retweets ≠ endorsement,” sharing someone else’s post also makes a claim.

Unfortunately, we fear that not enough people are viewing their online reading and writing as rhetorical, argumentative moves. To many people, it’s just a conversation, easily shared, easily set aside. But, over time, our online arguments – implicit or explicit – demonstrate more about who we are than how we see the world.

Learning to sift through the information has been, and will continue to be, an important skill. Learning to separate fact from opinion has been, and will continue to be, an important skill. Learning to separate claim from evidence, to confirm that evidence is seen as “fact” from a variety of sources and perspectives, and to ensure that discursive choices do not overpower the logic of the argument is becoming even more important in the current academic, social, and political climate.

As claims are expected to be accepted as truth without evidence to support them, either by media or by individuals, we must hone our skills of analysis. Long gone are the days where an appeal to authority alone is enough to simply prove something as “fact” or for an argument to be considered valid. We must demand logical arguments that are built on links between evidence and claims.

You dive deeply into the “moves” of argument of writing blogs, creating infographics, producing video and sharing within social media. Which of those forms of media are the trickiest for a teacher to bring into the classroom in terms of teaching digital argument with students? Why?

All of these forms of argument are tricky if we force students to “do” blogs, infographics, videos, or social media. If instruction is simply about the technology (or about the particular genre), then we may feel responsible as teachers for knowing all the possible technologies.

On the other hand, if we teach students how to read/view and then make an argument using various media, we can empower the students to select media that helps them to meet their purpose and to reach their intended audience. Ultimately, blogs may be the trickiest because they most resemble traditional forms of writing. We’ve seen many blogs (like some of those analyzed in the book) that do not use the affordances of digital writing – including strategic use of links, images, and other embedded media – to make arguments.

It’s tricky to shift our thinking from what we know, like persuasive writing in a traditional essay format, to see something in a completely new light… but it’s critical work to do.

What advice would you give a teacher who has been teaching “persuasive writing” techniques and now realizes that they must shift not just into “argument writing” but (as you argue in your book) into “digital argument writing”? How does a teacher make that manageable and integrated? Where do they even start?

When Kristen was teaching high school, she had this same revelation – that argument (claim, evidence, warrant, rebuttal) was the foundation of the reading and writing she needed to teach. Instead of persuasion, argument became the center of her classroom, and from September to June, she built her curriculum around the moves of argument.

Also, both of us have been part of National Writing Project Summer Institutes and sites for many years, so we know the power of having a network. We are not strangers to changing our own teaching and mindsets, so we understand how overwhelming it can be.

Starting small is important. Perhaps you could select one unit where you can transform the task from traditional to digital argument. Once you’ve had great success (and we know you will), reach out to us on Twitter or to Betsy, or Val, or Lauren, or Alex, or any of the teachers we profiled in the book. We’ve all moved from that small step to full integration, and we love to talk about teaching. :)

Thanks to you both for sharing these insights.

I have always felt that multimodal tools like Storify and Zeega were digital vehicles for argument, but that they do not fit the scaffolding suggested by Hicks and Turner. These tools are new opportunities for argument/persuasion that don’t fit in the old mold. Where do they fit in Hicks and Turner’s book?

I think we have an “old wine in new bottles” issue here. We fit the old wine of classical argumentation into the new digital bottles, but what of the brave new world of persuasion we see in the digital wild right now: tweetstorms, quote pix, bots, memes, etc? I believe that what Hicks and Turner have produced is a great intro for dealing with digital argumentation. Good on ’em. Now we need to get literate with these newer and hotter media as well.

Terry –

It’s true that Troy and Kristen do not cover every angle of New Media (there’s probably something new this week, right?). But they do lay the foundation for considering how different aspects of digital composition might be viewed, and perhaps used, for argument. Their premise of “everything is an argument” provides a path forward into helping teachers think about this shift in terms not just of school writing, but writing/literacy in life outside of the school day. Real writing.

Sure, they focus on some tools, but the scaffold and consideration they provide could easily be adapted for memes, tweetstorms, social networking, live video, and more.

You argue about “old wine/new bottles,’ and perhaps there is some truth in that, but I suspect that many teachers still need some anchor points around what they know (or at least know they want to know) before heading into the unknown terrain.

Thank for stopping by.

Sincerely,

Kevin

Kevin