5 Keys to Motivating Struggling Learners

In an Education Week report, Engaging Students for Success: Findings from a National Survey, the authors asked teachers for their perspective on a variety of topics. Several of their findings are pertinent.

✻ 87% of educators believe that student engagement and motivation are “very important to student achievement.” Engagement and motivation were ranked higher than teaching quality, parental support, or family background.

✻ 32% of educators strongly agreed that “I am good at engaging and motivating my students.”

✻ 68% of educators strongly agreed that “engaging and motivating students is part of my job duties and responsibilities.”

✻ Only 19% of educators strongly agreed that “I have adequate solutions and strategies to use when students aren’t engaged or motivated.”

How would your teacher colleagues respond to those statements? Would the results be similar in your school? Motivating struggling learners is a challenge, one that seems to grow over time. In this article, we’ll look at five keys to motivating struggling learners whether you are the teacher, an instructional coach, or the school leader.

Key One: Building a Relationship

The first key to motivating struggling learners is to build a positive relationship with each student. This is likely a priority for you and your teachers. I regularly see schools focusing on the caring aspect of school, and we should remember it truly is foundational to learning.

The old saying, “Students don’t care what you know until they know you care” is true. In addition to the standard getting-to-know-you activities and traditional methods of building a relationship, I’d like to share a new one for your teachers.

A creative way to learn about your students is through the use of Culture Boxes. At the beginning of the year, ask your students to put 7–10 items that represent different aspects of who they are into a shoebox. Your students will love this activity, so get lots of boxes of varying sizes.

As teacher educator Charlesetta Dawson explains,

“These objects reflect their family heritage, origins, ethnicity, language, religion, hobbies, and likes (foods, music, literature, movies, sports, etc.). The outsides of the boxes are decorated with pictures, symbols, and words/phrases to further explain who they are. Then the students share their culture boxes with the class.

“Every semester, my students always say that creating a culture box was their favorite activity because they got to be creative, share previously unknown information about themselves with their peers and teacher, and develop a better understanding of the similarities that we all have in common. The sharing might take more than one class period, but the time spent is well worth it!”

Fifth graders in Monticello NY share their culture boxes.

Part of building a relationship – the first step toward motivation – is getting to know your students. Culture boxes are an excellent way to accomplish that goal.

Key Two: Using Effective Praise

How often do you hear your teachers praising their students? Praise is a two-edged sword. It has benefits, such as building confidence and encouraging students, but there are also disadvantages. These typically occur when we overuse praise, which results in students becoming “praise junkies,” refusing to do anything unless they are complimented for the efforts.

I find that effective praise makes a difference with struggling students. As Daniel Pink says in his book, Drive, an extrinsic reward (praise falls in that category) is like caffeine—it can provide a jolt, but the jolt doesn’t last. With my struggling students, they needed praise to help them get started, especially because they had never felt successful in an academic setting. My encouragement and positive words helped fuel their desire to attempt the learning.

What does effective praise look like? There are six characteristics in this acrostic:

Effective PRAISE is:

- Positive

- Reinforces High Expectations

- Appropriate

- Independence is Promoted

- Sincere

- Effort and Progress are Noted

We should always be positive in our praise. I’ve seen teachers use sarcasm with students, and that usually backfires. Our praise should reinforce high expectations. In other words, don’t praise for substandard work. It should also be appropriate, which means it should be directly tied to something a student has done and it should be shared in a timely manner.

We should also promote independence, so students do not become dependent on our opinion of their work. For example, I often asked my students what they thought about their work before I gave them my opinion. Of course, praise should be sincere, since students are turned off by fake praise.

Finally, reinforcing effort and progress along with achievement is critical. In this case, you might say something like “I noticed how hard you worked on that math problem. Sticking with it really made a difference.”

Key Three: Developing a Growth Mindset

The third key to motivating struggling learners is to develop a growth mindset in your classrooms. There are several ways to create a growth mindset; let’s look at two.

Ensure a Learning-Oriented Mindset — First, we need to ensure that students have a learning-oriented mindset. Often, they don’t. Most of my struggling learners had given up, believing they could never learn. I’ll never forget Erika, who said, “Why are you bothering? Don’t you know I’m stupid?”

We start the process by having a growth mindset ourselves, then constantly and consistently reinforcing it with students. We do this by providing the right support for them to learn, encouraging them along the path , and celebrating their resilience and successes. As a part of this, we should teach them to use positive language with themselves, such as “This is challenging for me but with some help, I believe I can learn the water cycle.”

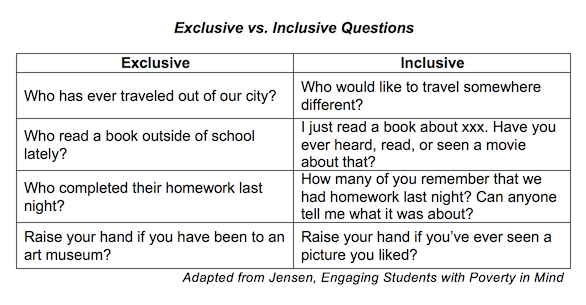

Teachers can also ensure that all students are engaged in the learning process. A specific questioning technique that is particularly effective for struggling learners is the use of exclusive and inclusive questions.

In Engaging Students with Poverty in Mind, Erik Jensen (2013) describes the difference between exclusive and inclusive questions. Particularly when we are activating prior knowledge, we ask questions to elicit students’ experiences. However, at times, our questions may exclude struggling students, since they may not have a wide base of experiences.

Instead, use questions that are more inclusive. Take a look at the samples below.

Focus on Process as Well as Product — Another thing we can do to help students develop a growth mindset is to encourage them to focus on the process of learning, not just on the product. Many of my students just wanted to “get finished.” They wanted to do their assignments quickly, and whether they were right or not didn’t matter. After all, they weren’t that smart anyway, right?

Use these questions to help students focus on the Learning Process:

Before: What do you think you know? What are you unsure about? For older students: What strategy might help you with this?

During: What questions do you have? Where did you look for help? What strategy(ies) did you try?

After: What strategies helped you complete your work? How were you successful?

We need to help students slow down and focus on what they are learning and how they are learning. I used a three step questioning process for students. With older students, they can use these questions for self-assessment; with younger ones, use the questions as verbal prompts.

Key Four: Holding High Expectations

The fourth key to motivating struggling learners it to hold high expectations for each student. Do your teachers have high expectations? Of course they do. I’ve never met a teacher who said, “I have low expectations for my students.” The challenge is that we sometimes have hidden low expectations of certain students.

For example, one year, several teachers “warned” me about Daniel, a new student in my class. During class, he certainly lived up to (really, down to) the teachers’ comments. Despite my efforts, and to my shame, my expectations for him became lower. We have to be on guard to ensure that we keep high expectations in place for every single student. But we also have to put those expectations into action.

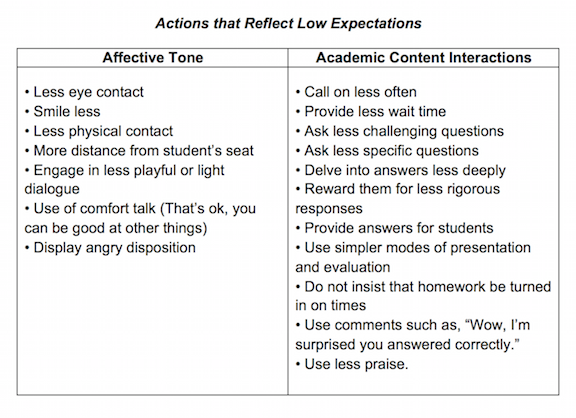

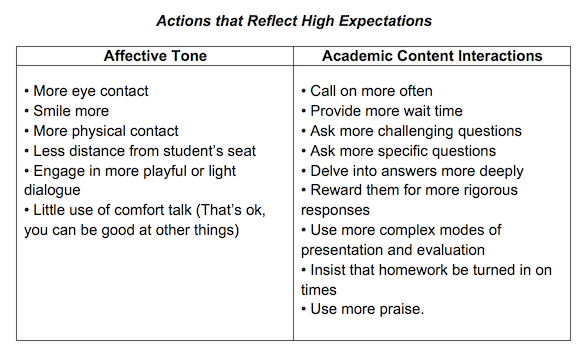

Many researchers have detailed specific actions we take that are reflective of low expectations. I’ve used Robert Marzano’s (2010) categories of our affective tone and our academic content interactions to provide a summary.

The opposite is also true. When we have high expectations, we act in certain, converse ways. Which do you use with your struggling students?

Key Five: Providing Appropriate Support

Another key to motivating struggling learners is to provide them with support and scaffolding. Consider a time when you tried to accomplish something new. For example, think about your first year as a principal. Did you need help or guidance?

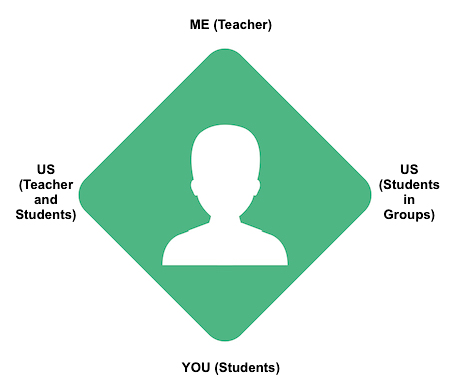

That’s exactly how our students are as they move to higher levels of learning. However, you will want to provide different levels of support at different times, gradually moving them to independence.

It’s important to realize that support should be used at an appropriate level through the learning process. At the beginning of new learning, more support is needed. As the learning continues, we want students to become more independent in their learning. This is called gradual release.

One way to think about scaffolding is with a diamond, or rhombus. As you can see from the figure below, it starts with Me (meaning the teacher). The teacher begins by modeling a lesson. Next, we go to Us. There are two parts of this. First is the teacher and the students (us) going through guided practice together. The second part of guided practice is also us, meaning students working with partners or in small groups. Finally, the student (You) does the work independently.

If you are in a coaching role, as your teachers build support and scaffolding activities for their students, consider the following guidelines. Support must be planned in advance, and then adjusted throughout lessons. Using the reminders below will help your teachers craft the most effective scaffolding for their students.

Effective SUPPORT

- S Structured

- U Understanding is the Result

- P Provides for Differentiation

- P Promotes Connections

- O Optimizes Strategic Learning

- R Repetitionless

- T Tied to Memory

The Goal: Long-term Results

Students can be motivated for a variety of reasons, which can include personal factors, school influences, and outside issues. We can use extrinsic rewards to influence motivation, but they may only provide short-term results. Using these five keys will help your students—and teachers—become more motivated with long-term results.

Barbara is the author of Scaffolding for Success (Routledge/Eye On Education, 2025) and many other books and articles about teaching and leadership. Visit her website and see some of her most popular MiddleWeb articles about effective teaching and support for new teachers here.

Thank you so much for including specific examples to support your claims. With these strategies and mindsets even the most experienced educators will be inspired and improve.

I like Eric Jensen’s work. In fact, I have been to 8 of his workshops in a year. He walks his talk because he asks inclusive questions in his workshops too.

I like the building the relationship piece, because healthy relationships help to cut down on barriers between teacher/student and discipline issues in class.