8 Strategies to Quickly Assess Prior Knowledge

Prior to teaching your lesson, it’s important to gauge where students are in their knowledge of the topic. We are going to look at eight simple strategies you can use to assess students before you design and carry out your lesson plan.

1. Discover the Mistakes

For the topic you will be teaching, create a webpage or blog entry that mimics an online encyclopedia entry. Include at least four content errors. Ask students to compare the webpage to a credible site, such as the National Geographic Channel. Their task is to correct the mistakes. This is a great way to build some prior knowledge and hone students’ analysis skills.

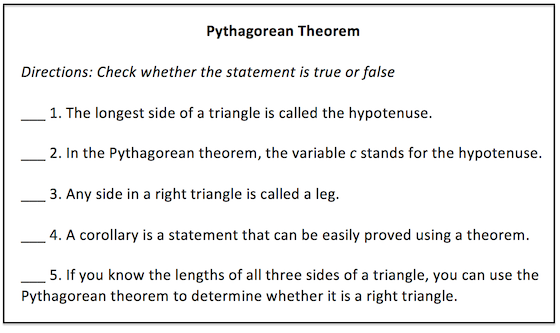

2. Anticipatory Guide

It’s important to determine what a student actually understands about a concept prior to instruction. Pat Vining, a math teacher, uses a simple activity to check her students’ prior knowledge of the concept and to clear up any misunderstandings students may have about the topic.

First, Pat gives students three minutes to answer a short true/false questionnaire. Next, in pairs, students compare responses and use the textbook to check their answers. Each set of partners must rewrite any false statements so that they are true. She ends with a whole-class discussion to ensure understanding.

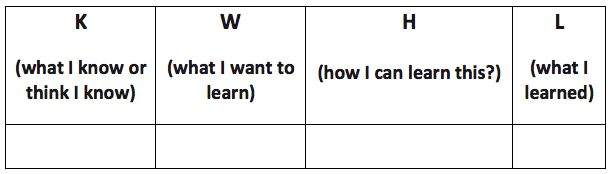

3. The K-W-H-L Tool

Probably the most common method of identifying students’ prior knowledge that I see in classrooms today is a KWL chart. During a KWL activity, you ask the students what they already know about a topic (K) or what they think they know about it. Next, you ask what they want to know (W). Then, you teach the lesson and ask them what they learned (L). You can also add an H—How Can We Learn This to create a K-W-H-L organizer, which shifts ownership of learning to students.

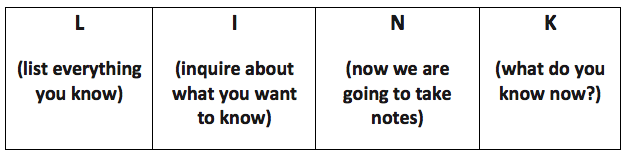

4. LINK Strategy

Kendra Alston adapts the KWL strategy into a LINK for her students.

It’s important to share students’ responses with everyone, albeit it in a safe way that doesn’t embarrass anyone. That’s why I like her method. She starts by allowing each student to write an individual response, so everyone has an opportunity to think about what they know.

As Kendra points out, if I’m a student,

“…by sharing with a partner, I can feel ‘safer’ in case I’m not right. In the whole class discussion, I’m sharing ‘our’ answers (mine and my partner’s), so I don’t feel like I’m out on a limb by myself. You could even add another option of sharing with two groups of partners before you share with everyone.

Kendra adds another step:

“However, don’t sacrifice the whole class discussion. We all learn more together, and it’s a safe guess that someone in my class knows something I don’t know. Listening to all responses and charting them out for everyone to see helps me build prior knowledge when I don’t have much.”

5. Alike / Red Herring

I sometimes wondered how much my students knew before I told them the topic for the day. One day, I decided to let them figure out the topic first. I named multiple cities, such as Raleigh, North Carolina, Sacramento, California, and Albany, New York. After a few seconds, one student shouted, “Hey, I know—those are all state capitals!”

This is an easy way to determine what students already know, and it can be used at any grade level. A pre-kindergarten teacher can use it to introduce the color of the day, pulling items out of a box. A science teacher can use this strategy to introduce elements or subatomic particles.

To increase the rigor, Lindsay Yearta uses the “Red Herring” game with her students. She gives multiple examples that are linked, but students must identify the red herring – that’s the one that does NOT belong. Take a look at these: Arizona, Alabama, Virginia, and California. Arizona doesn’t belong because it doesn’t have a coastline. Students must also justify their choice. Again, based on their responses, you can see how much they know, and by shifting the focus to students generating information, it is more rigorous.

6. If / Then Statements

Jayne Bartlett, author of Outstanding Assessment for Learning in the Classroom, describes another rigorous method we can use to assess prior knowledge. Using if/then statements, students identify a connection and apply it.

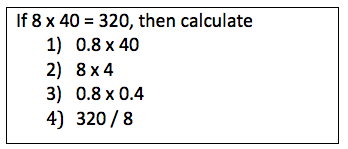

Sample Math If/Then Statements

on Multiplication and Division

She explains, “to extend the if/then strategy, you can ask pupils to determine a simple rule: ‘If: taste –> tasting, heat –> heating, place –> placing, time –> timing, meet –> meeting… then what is the rule?”

Once again, by requiring students to analyze the information on their own before you step in, you have increased the rigor.

7. Word Sorts

Word sorts also allow you to see how much students know. In small groups, give students a set of vocabulary cards. Ask them to discuss the words and group them based on whether or not they fit in with the topic. Then, after reading a text, students revisit their word groupings and sort them again. To up the rigor even more, preview the topic and have students generate related words on their own before reading the text.

8. Write the Room

A final way to gauge prior knowledge is by taping posters around the room. On each one, write a word or phrase related to your topic. As students enter, they move from poster to poster writing something they know about the word or phrase. In other words, they “write the room.” Use stickies if you have multiple classes.

Conclusion

Assessing students’ prior knowledge allows you to customize your teaching to meet their needs. These simple and adaptable strategies can help you gain an understanding of what your students do and do not know in short order.

_______________

A nationally recognized expert in the areas of rigor and motivation, she collaborates with schools and districts for professional development. Barbara can be reached through her website or her blog. Follow her on X-Twitter @BarbBlackburn.

Loved the LINK idea–I will use it and credit Kendra Alston. Thanks!

This is of great help to me and my students

I really like the link idea. I already do a lot of KWL charts with social studies.

I like the way the strategies are explained. Thanks a lot, Ms. Barbara, for helping me to develop through resources like the above. Look forward to more future learning from you.

Thank you very much for the explanation and it is well discussed. I was looking for the answer to my lesson plan and I got it.